By KPMG

Introduction

This report addresses three fundamental decisions that face a prospective purchaser:

- What should be acquired: the target’s shares or its assets?

- What will be the acquisition vehicle?

- How should the acquisition vehicle be financed?

Of course, tax is only one piece of transaction structuring. Company law governs the legal form of a transaction, and accounting issues are also highly relevant when selecting the optimal structure. These areas are outside the scope of this report, but some of the key points that arise when planning the steps in a transaction plan are summarized later in this report.

Recent developments

New Zealand’s recent tax developments with regard to mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are set out in the relevant sections of this report.

Case law

A number of court wins for the Inland Revenue Department (IRD) on the application of New Zealand’s general tax anti-avoidance rule have implications for transactions and structures adopted for inbound investment. For example, the New Zealand Court of Appeal decision in Alesco v CIR involved a taxpayer unsuccessfully appealing a tax avoidance finding on the use of cross-border optional convertible notes as a funding structure.

A greater level of consideration has been given by the courts (and IRD) to what is regarded as the commercial reality and economic effects of transactions. Reliance on the legal form of the transaction or the structure used is no longer a suitable defense. This has inevitably increased uncertainty over what is acceptable tax planning.

Base erosion and profit shifting

The New Zealand government, like most other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, has expressed concern about the impact of base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) by multinationals. New Zealand is engaging with the OECD on its Action Plan on BEPS.

However, the government’s response to date has been cautious. Legislatively, changes have been made to tighten the interest deductibility rules for non-residents, by extending New Zealand’s thin capitalization rules to groups of non-residents ‘acting together’. Further proposals include changes to non-resident withholding tax (NRWT) rules aimed at removing the ability for non-residents to shift profits out of New Zealand with no or minimal tax paid under the NRWT rules.

KPMG in New Zealand expects a number of other tax changes will be made in due course.

Inland revenue activity

In its annual tax compliance guide for businesses, the IRD has focused on aggressive tax planning (e.g. financing and transfer pricing transactions by multinationals). The IRD’s focus areas largely align with the OECD’s key areas of concerns.

Therefore, for non-residents looking to invest in New Zealand, attention needs to be given to ‘future-proofing’ inbound investment structures, in view of possible legislative changes. This includes changes arising from potential global BEPS developments (e.g. enhanced transfer pricing rules and/or changes to rules governing the treatment of hybrid instruments and entities) and changes to address New Zealand domestic issues, such as the introduction of a general capital gains tax (a broad capital gains tax was a policy of a major opposition party during the 2014 general election.)

From a New Zealand tax perspective, factors that may influence cross-border inbound investment decisions include:

- comparative methods of funding the investment

- type of operating entity best suited to a particular investment

- quantum of tax arising when profits are distributed

- alternatives available for realizing the investment and repatriating the proceeds.

Update of New Zealand’s treaty network

New Zealand has signed new tax treaties with Canada, Japan, Papua New Guinea, Samoa and Vietnam.

The most significant changes in the new treaties are to withholding tax (WHT) rates, with reductions in rates for dividends, interest and royalties. These new treaties also contain anti-treaty shopping rules.

Ongoing discussions to update and revise existing tax treaties continue in respect of a number of major jurisdictions including China, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Negotiations of a tax treaty with Luxembourg are ongoing.

New Zealand has significantly expanded its tax information exchange agreement (TIEA) network in recent years. TIEAs were signed with a number of traditional offshore jurisdictions, including the British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands and Jersey. Negotiations for TIEAs with Monaco and Macao, among other jurisdictions, are underway.

Asset purchase or share purchase

New Zealand does not have a comprehensive capital gains tax. As a result, gains on capital assets are subject to tax only in certain limited instances, for example, where the business of the taxpayer comprises or includes dealing in capital assets, such as shares or land, or where the asset is acquired for the purpose of resale. The fact that capital gains are usually not subject to tax in New Zealand has an impact on the asset versus share purchase decision.

Purchase of assets (excluding land)

A purchase of assets usually results in the base cost of those assets being reset at the purchase price for tax depreciation (capital allowance) purposes. This may result in a step-up in the cost base of the assets (although any increase may be taxable to the seller).

Historical tax liabilities generally remain with the company and are not transferred with the assets. The purchaser may still inherit defective practices or compliance procedures. Thus, a purchaser may wish to carry out some tax due diligence to identify and address such weaknesses (e.g. through appropriate indemnities).

Purchase of land

A purchase of land usually results in the base cost being reset at the purchase price. However, there is no allowance for tax depreciation for land or buildings with an estimated useful life of 50 years or more (see further below).

Newly enacted legislation imposes disclosure requirements on transferors and transferees of New Zealand land. The requirements include buyers and sellers’ tax details, such as their New Zealand IRD number, tax residence status and foreign tax information if non-resident (e.g. the country of tax residence and foreign tax identification number).

All buyers and sellers, including non-residents, must provide a New Zealand IRD number. To receive an IRD number, a non-resident needs to have a fully functioning New Zealand bank account (i.e. capable of withdrawals as well as deposits) and provide evidence of this to Inland Revenue. This will require the New Zealand bank to have confirmed the non-resident’s identity through anti-money laundering and countering financing of terrorism checks.

Purchase price

No statutory rules prescribe how the purchase price is to be allocated among the various assets purchased. Where the sale and purchase agreement is silent as to the allocation of the price, the IRD generally accepts a simple pro rata allocation between the various assets purchased on the basis of their respective market values.

Goodwill

Goodwill paid for a business as a going concern is not deductible, depreciable or amortizable for tax purposes. For this reason, where the price contains an element of goodwill, it is common practice for the purchaser to endeavor to have the purchase and sale agreement properly allocate the purchase price between the tangible assets and goodwill to be acquired.

This practice is not normally challenged by the IRD, provided that the purchase price allocation is agreed between the parties and reasonably reflects the assets’ market values.

If the sale and purchase agreement is silent as to the allocation of the price, a simple pro rata allocation between the various assets purchased, on the basis of their respective market values, is usually accepted.

It may be possible to structure the acquisition of a New Zealand investment in such a way as to reduce the amount of goodwill that is acquired. Given that certain intangible assets can be depreciated in New Zealand (see later in this report), a sale and purchase agreement could apportion part of the acquisition price to certain depreciable intangible assets, rather than non-depreciable goodwill.

Depreciation

Most tangible assets may be depreciated for income tax purposes, the major exceptions being land and, more recently, buildings (see below). Rates of depreciation vary depending on the asset. Taxpayers are free to depreciate their assets on either a straight-line or diminishing-value basis.

The 20 percent loading (uplift in depreciation rates), which formerly applied to acquired assets (excluding buildings and secondhand imported vehicles), ceased to apply to all items of depreciable property acquired, or in respect of which a binding contract is entered into, on or after 21 May 2010. In addition, as of the 2011–12 income year, no depreciation can be claimed on buildings with an estimated useful life of 50 years or more. (Building owners can continue to depreciate 15 percent of the building’s adjusted tax value at 2 percent per year where all items of building fit-out, at the time the building was acquired, have historically been depreciated as part of the building.)

As of 21 May 2010, capital contributions toward depreciable property must be treated by the recipient as income spread evenly over 10 years or as a reduction in the depreciation base of the asset to which the contribution relates. (Examples include capital contributions payable to utilities providers by businesses to connect to a network.)

Before 21 May 2010, capital contributions of this type were treated as non-taxable to the recipient and the cost of the resulting depreciable property was not reduced by the amount of the contribution.

While the cost of intangible assets generally cannot be deducted or amortized, it is possible to depreciate certain intangible assets. The following assets (acquired or created after 1 April 1993) may qualify for an annual depreciation deduction, subject to certain conditions:

- the right to use a copyright

- the right to use a design model, plan, secret formula or process or any other property right

- a patent or the right to use a patent

- a patent application with a complete specification lodged on or after 1 April 2005

- the right to use land

- the right to use plant and machinery

- the copyright in software, the right to use the copyright in software, or the right to use software

- the right to use a trademark.

Other intangible rights that qualify for an annual depreciation deduction include:

- management rights or license rights created under the Radio Communications Act 1989

- certain resource consents granted under the Resource Management Act 1991

- the copyright in a sound recording (in certain circumstances)

- plant variety rights, or the right to use plant variety rights, granted under the Plant Variety Rights Act 1987 or similar rights given similar protection under the laws of a country or territory other than New Zealand as of the 2005–06 income year.

Depreciation may be recovered as income (known as ‘depreciation recovery income’) where the disposal of an asset yields proceeds in excess of its adjusted tax value. Special rules apply to capture depreciation recovery income in respect of depreciation previously allowed for software acquired before 1 April 1993 and the amount of any capital contribution received for that item.

Tax attributes

Tax losses and imputation credits are not transferred on an asset acquisition. They remain with the company.

Value added tax

New Zealand has a value added tax (VAT), known as the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The rate is currently 15 percent and must be charged on most supplies of goods and services made by persons who are registered for GST.The sale of core business assets to a purchaser by a registered person constitutes a supply of goods for GST purposes and, in the absence of any special rules, is charged with GST at the standard rate.

However, if the business is a going concern, it can be zero-rated by the vendor (charged with GST but at 0 percent). To qualify for zero rating:

- both the vendor and purchaser must be registered for GST

- the vendor and purchaser must agree in writing that the supply is of a going concern

- the business must be a going concern

- the purchaser and vendor must intend that the purchaser should be capable of carrying on the business.

Sales consisting wholly or partly of land must be zero rated by the vendor where both the vendor and the purchaser are registered for GST at the time of settlement and the purchaser intends to use the property for GST taxable supply purposes.

‘Land’ is defined broadly and includes a transfer of a freehold interest and, in most circumstances, the assignment of a lease but not periodic lease payments.

Where the sale is of land and other assets, then the whole sale must be zero rated, not just the land component.

As the GST risk is with the vendor if it incorrectly zero-rates the supply, the purchaser must provide a written statement to the vendor attesting to the following points:

- The purchaser is a registered person or will be registered at the time of settlement.

- The purchaser is acquiring the land with the intention of using it to make taxable supplies.

- The purchaser does not intend to use the land as their own or an associate’s principal place of residence.

If the sale is to a nominee, then it is the status of the nominee that is relevant.

In most cases, the purchase price is expressed as ‘plus GST’, if any, thereby granting the vendor the right to recover from the purchaser any GST later assessed by the IRD. However, this must be expressly stated. If the contract is silent, the price is deemed to be inclusive of GST.

Where the sale of assets cannot be zero rated, the purchaser may recover the GST paid to the vendor from the IRD, provided the purchaser is registered for GST or is required to be registered for GST at the time the assets are supplied by the vendor. Goods and services are supplied at the earlier of the time that the vendor receives a payment (including a deposit) or the vendor issues an invoice. An invoice is defined as a document giving notice of an obligation to make a payment.

Assets imported into New Zealand are subject to GST of 15 percent at the border.

New Zealand has a reverse charge on imported services to align the treatment of goods and services. However, the impact of the GST on imported services affects only organizations that make GST-exempt supplies (e.g. financial institutions). Organizations that do not make GST-exempt supplies are not required to pay a reverse charge.

Transfer taxes

No stamp duty is payable on sales of land, improvements or other assets.

Purchase of shares

The purchase of a target company’s shares does not result in an increase in the base cost of the company’s underlying assets; there is no deduction for the difference between underlying net asset values and consideration, if any.

Tax indemnities and warranties

In a share acquisition, the purchaser acquires the target company together with all related liabilities including contingent liabilities. Consequently, in the case of negotiated acquisitions, it is usual for the purchaser to request, and the vendor to provide, indemnities and/or warranties in respect of any historical taxation positions and taxation liabilities of the company to be acquired. The extent of the indemnities and warranties is a matter for negotiation.

Tax losses

To carry forward tax losses from 1 income year to the next, a company must maintain a minimum 49 percent shareholder continuity from the start of the income year in which the tax losses were incurred. Unlike some jurisdictions, New Zealand does not have a same-business test, so the ability to carry forward and use tax losses is solely based on the shareholder continuity percentage.

Where there is a minimum 66 percent commonality of shareholding from the beginning of the income year in which the tax losses were incurred, a company potentially can offset its tax losses with another group company. It is difficult to preserve the value of tax losses post-acquisition, as there is limited scope to refresh tax losses.

Crystallization of tax charges

Caution should be exercised where the purchaser is acquiring shares in a company that is a member of a consolidated income tax group, because the target company will remain jointly and severally liable for the income tax liability of the consolidated income tax group that arose when the target company was a member. The IRD may grant approval for the target company to cease to be jointly and severally liable.

In addition, a comprehensive set of rules applies to capture income arising on the transfer of certain assets out of a consolidated tax group where they have previously been transferred within the consolidated tax group to the departing member of that group. The disposal of shares in a company holding the transferred assets constitutes a sale of that asset out of the consolidated tax group; for tax purposes, the company is deemed to have disposed of the asset immediately before it leaves the consolidated tax group and to have immediately reacquired it at its market value. This rule applies to transfers of ‘financial arrangements’ (e.g. loans), depreciable property and, in some situations, trading stock, land and other revenue assets.

Pre-sale dividend

New Zealand operates an imputation system of company taxation. Shareholders of a company gain relief against their own New Zealand income tax liability for income tax paid by the company. Tax payments by the company are tracked in a memorandum account, called an ‘imputation credit account’, which records the amount of company tax paid that may be imputed to dividends paid to shareholders. New Zealand-resident investors use imputation credits attached to dividends to reduce the tax payable on the dividend income.

To carry forward imputation credits from 1 imputation year to the next, a company must maintain a minimum of 66 percent shareholder continuity from the date the imputation credits are generated.

Where imputation credits are to be forfeited (e.g. on a share sale that will breach the minimum 66 percent shareholder continuity), then a taxable bonus issue (TBI) generally may be used to preserve the value of the imputation credits that would otherwise be lost.

The advantage of a TBI is that it achieves the same outcome as a dividend in respect of crystallizing the value of imputation credits for the ultimate benefit of the company’s shareholders. However, since a TBI does not require cash to be paid, the solvency of the company is not adversely affected and there is no WHT cost.

The TBI essentially converts retained earnings to available subscribed capital (ASC) for income tax purposes. This ASC can then be distributed tax-free to the company’s shareholder(s) in the future (e.g. on liquidation of the company or as part of a capital reduction), where certain conditions are met.

The TBI provides a potential benefit to the purchaser but no benefit to the vendor. This is something the purchaser may need to raise with the vendor.

Transfer taxes

No stamp duty is payable on transfers of shares or on the issue of new shares.

Tax clearances

A party to a transaction can seek a binding ruling from the IRD on the tax consequences of an acquisition or merger. However, it is not possible to obtain an assurance from the IRD that a potential target company has no arrears of tax and is not involved in a tax dispute.

Choice of acquisition vehicle

The following vehicles may be used to acquire the shares and/or assets of the target:

- local holding company

- foreign parent company

- non-resident intermediate holding company

- branch

- joint venture

- other special purpose vehicles (e.g. partnership, trust or unit trust).

Local holding company

Subject to thin capitalization requirements, a local holding company may be used as a mechanism to allocate interest-bearing debt to New Zealand (i.e. the local holding company borrows money to help fund the acquisition of the New Zealand target).

From a New Zealand perspective, a tax-efficient exit strategy involves selling the shares of the local holding company as opposed to selling the shares of the underlying operating subsidiary. Where the shares in the underlying operating subsidiary are sold, a WHT liability arises on the repatriation of any capital profit unless an applicable tax treaty reduces the WHT rate (potentially to 0 percent; see below).

The imputation credit regime reduces the impact of double tax for New Zealand-resident shareholders. New Zealand-resident investors use imputation credits attached to dividends to reduce the tax payable on dividend income received from New Zealand-resident companies.

For non-resident shareholders, dividends are subject to NRWT at either 15 percent if fully imputed or 30 percent if not (most tax treaties limit this rate to 15 percent or less in the case of some recently renegotiated treaties).

The domestic rate of NRWT payable is 0 percent where a dividend is fully imputed and a non-resident investor holds a 10 percent or greater voting interest in the company (or where the shareholding is less than 10 percent but the applicable post-treaty WHT rate on the dividend is less than 15 percent; New Zealand currently has no treaties where this is the case).

For non-resident investors with shareholdings of less than 10 percent, the 15 percent WHT rate on fully imputed dividends can be relieved under the foreign investor tax credit (FITC) regime. This regime essentially eliminates NRWT by granting the dividend-paying company a credit against its own income tax liability where the company also pays a ‘supplementary dividend’ (equal to the overall NRWT charge) to the non-resident.

For GST purposes, the holding company and the operating company should be grouped. This allows the holding company to recover GST on expenses paid. Alternatively, a management fee may be charged from the holding company to the operating company.

Foreign parent company

The foreign purchaser may choose to make the acquisition itself, perhaps to shelter its own taxable profits with the financing costs.

Non-resident intermediate holding company

Where the foreign country taxes capital gains and dividends received from overseas, an intermediate holding company resident in another territory could be used to defer this tax and perhaps take advantage of a more favorable tax treaty with New Zealand. However, as noted earlier, increased attention is being paid globally to structures in an effort to target BEPs concerns. In addition, most new tax treaties have anti-treaty shopping provisions that may restrict the ability to structure a deal in a way designed solely to obtain tax benefits.

Local branch

New Zealand-resident companies and branches established by offshore companies are subject to income tax at 28 percent of taxable profits.

In most cases, the choice between operating a New Zealand company or branch is neutral for New Zealand tax purposes because of the changes to the domestic NRWT rules (for shareholdings of 10 percent or more; see local holding company section) and the application of the FITC regime (for shareholdings less than 10 percent).

A branch is not a separate legal entity, so its repatriation of profits is not considered a dividend to a foreign company and NRWT is not imposed. The effective tax rate on a New Zealand branch operation is therefore 28 percent.

In effect, New Zealand’s thin capitalization and transfer pricing regimes apply equally to branch and subsidiary operations. In practice, however, the application of New Zealand’s transfer pricing rules to branches and subsidiaries can differ in some aspects.

Joint venture

Where an acquisition is to be made in conjunction with another party, the question arises as to the most appropriate vehicle for the joint venture. Although a partnership can be used, in most cases, the parties prefer to conduct the joint venture via a limited liability company, which offers the advantages of incorporation and limited liability for its members. In contrast, a general partnership has no separate legal existence and the partners are jointly and severally liable for the debts of the partnership, without limitation.

Limited partnership

New Zealand has special rules for limited partnerships that may make them more attractive than general partnerships for joint venture investors. The key features of limited partnerships are as follows:

- Limited partners’ liability is limited to the amount of their contributions to the partnership.

- Limited partners are prohibited from participating in the management of the limited partnership. They may undertake certain activities (safe harbors) that allow them to have a say in how the partnership is run without being treated as participating in the management of the partnership and losing their limited liability status.

- A limited partnership is a separate legal entity to provide further protection for the liability of limited partners.

- Each partner in a limited partnership is taxed individually, in proportion to their share of the partnership income, in the same way that income from general partnerships is taxed.

- Limited partners’ tax losses in any given year are restricted to the level of their economic loss in that year.

By contrast, an incorporated joint venture vehicle does not offer the same flexibility in respect of the offset of tax losses. Grouping of tax losses arising in a company is limited to the extent that the loss company and the other company were at least 66 percent commonly owned in the income year in which the loss arose and at all times up to and including the year in which the loss offset arises.

A key issue with limited partnership structures is that thin capitalization is tested for each partner (not the limited partnership), which may restrict the ability to gear New Zealand investments without loss of interest deductions. The thin capitalization rules are discussed later in this report.

Choice of acquisition funding

A purchaser using a New Zealand acquisition vehicle to carry out an acquisition for cash needs to decide whether to fund the vehicle with debt, equity or a hybrid instrument that combines the characteristics of both (although care should be taken with hybrid instruments in the current tax environment). The principles underlying these approaches are discussed later in this report.

GST paid on costs incurred in issuing or acquiring debt instruments is not generally recoverable. However, it may be recoverable where the instruments are issued to an offshore investor or to a New Zealand-registered investor that makes more than 75 percent taxable supplies.

For equity funding, GST on costs incurred in issuing equity is not generally recoverable. Again, however, the GST may be recovered where the shares are issued to a non-resident, investor or entity that is more than 75 percent taxable.

GST on equity acquisition costs (including evaluation of the investment) is recoverable where there is an acquisition of an interest of greater than 10 percent, the investor is able to influence management, and the shares are acquired in a non-resident or in an entity that makes more than 75 percent taxable supplies.

Debt

The principal advantage of debt is the availability of tax deductions in respect of the interest (see deductibility of interest below). In addition, a deduction is available for expenditure incurred in arranging financing in certain circumstances. In contrast, the payment of a dividend does not give rise to a tax deduction.

To fully utilize the benefit of tax deductions on interest payments, it is important to ensure that there are sufficient taxable profits against which the deductions may be offset.

In an acquisition, it is more common for borrowings to be undertaken by the new parent of the target (rather than the target itself) and for any cash flow requirements of the borrowing parent to be met by extracting dividends from the target. Provided the companies are part of a wholly owned group, dividends between the companies are exempt.

This structure is also a more efficient for GST purposes because, in some cases, any lending activities of the parent could cause the GST paid on expenses to not be fully recoverable.

Deductibility of interest

Subject to the thin capitalization and transfer pricing regimes (discussed later in this report), most companies can claim a full tax deduction for all interest paid, without regard to the use of the borrowed funds. For other taxpayers, the general interest deductibility rules apply.These rules allow an interest deduction where interest is:

- incurred in gaining or producing assessable income or excluded income for any income year

- incurred in the course of carrying on a business for the purpose of deriving assessable income or excluded income for any income year

- payable by one company in a group of companies on monies borrowed to acquire shares in another company included in that group of companies (a company deriving only exempt income can only deduct interest in limited situations, e.g. where the exempt income is from dividends).

Where a local company is thinly capitalized, interest deductions are effectively removed through the creation of income to the extent that the level of debt exceeds the thin capitalization ‘safe harbor’ debt percentage. Generally, a New Zealand company is regarded as thinly capitalized where it exceeds a safe harbor of 60 percent in respect of its debt percentage (reduced from 75 percent as of the 2011–12 income year) and the applicable debt percentage for the New Zealand group also exceeds 110 percent of the debt percentage for the worldwide group. A change with effect from 1 April 2015 means that debt originating from shareholders are excluded when calculating the debt level of a company’s worldwide operations.

The inbound thin capitalization regime also applies when non-residents who appear to be acting together own 50 percent or more of a company. Non-residents are treated as acting together if they hold debt in a company in proportion to their equity, have entered into an arrangement setting out how to fund the company with related-party debt, or act on the instructions of another person (i.e. a private equity manager) in funding the company with related-party debt. Increases in asset values following internal company reorganizations are ignored, unless the increase in asset value would be allowed under generally accepted accounting principles in the absence of the reorganization, or if the reorganization is part of the purchase of the company by a third party.

The thin capitalization rules also apply to outbound investment by a New Zealand company, i.e., where a New Zealand parent debt-funds its offshore operations. In this case, the relevant debt percentage is 75 percent. An additional safe harbor applies for outbound investments, provided the ratio of assets in the New Zealand group is 90 percent or more of the assets held in the worldwide group and the interest deductions are less than 250,000 New Zealand dollars (NZD).

There is an alternative thin capitalization test for New Zealand companies with outbound investments that have high levels of arm’s length debt (provided certain other conditions are met). These companies can choose a test for thin capitalization based on a ratio of their interest expenses to pre-tax cash flows, rather than on a debt-to-asset ratio.

Where a New Zealand company becomes subject to inbound thin capitalization due to ownership by a non-resident owning body, it must treat its New Zealand group assets/debt as its worldwide group assets/debt when applying the 110 percent of the worldwide group debt percentage safe harbor test.

Generally, the funding of a subsidiary by a parent through the use of interest-free loans does not produce any adverse taxation consequences. Such loans are not included in thin capitalization calculations for New Zealand income tax purposes. However, an interest-free loan from a subsidiary to its parent could be deemed to be a dividend, thereby creating assessable income for the parent company. Such transactions are also potentially subject to the transfer pricing regime where the counter-party is a non-resident.

The timing of the deductibility of interest on financial arrangements (widely defined to include most forms of debt) is governed by legislation known locally as the ‘financial arrangements’ rules.

These rules require that interest be calculated in accordance with one of the prescribed spreading methods. These rules do not apply to non-residents, except in relation to financial arrangements entered into by non-residents for the purpose of a fixed establishment (i.e. branch) situated in New Zealand.

Withholding tax on debt and methods to reduce or eliminate it

WHT is imposed on interest payments and dividend distributions between New Zealand residents (with some exceptions) unless a certificate of exemption is obtained.

Entities with gross assessable income (before deductions) of NZD2 million or more are entitled to an exemption certificate, along with financial institutions, exempt entities, entities in loss situations and certain others. Interest payments and dividend distributions paid and received by companies within the same wholly owned group are not subject to WHT.

NRWT is imposed on interest, dividends and royalties paid to non-residents. The domestic rate of NRWT on payments of interest is 15 percent; however, most tax treaties reduce this rate to 10 percent (and 0 percent in the case of some recent tax treaties, where the lender is a financial institution that is not associated with the borrower).

There are limited opportunities to reduce the NRWT on payments of interest by a New Zealand-resident payer to a related non-resident recipient.

The approved issuer levy (AIL) regime can be applied instead of NRWT in the case of interest payments to non-residents who are not associated with the New Zealand payer. On confirmation of ‘approved issuer’ status by the IRD, interest payments to the relevant non-resident lender are exempt from NRWT and instead subject to the payment of a levy equal to 2 percent of the interest.

Changes are currently being proposed to the way the NRWT and AIL regimes operate for related-party cross-border debt:

- The changes would extend NRWT to income arising under the financial arrangements rules, rather than simply ‘interest paid’, and the liability to pay NRWT would also be triggered under those rules.

- NRWT, rather than AIL, would apply to:

— back-to-back loans involving third-party lenders if a non-resident associate of the New Zealand borrower provides funds to the third party lender

— loans made by a group owning more than 50 percent of the New Zealand resident borrower and ‘acting together’, mirroring recent thin capitalization rule changes.

- The AIL regime would be limited to loans made to or from a financial intermediary (e.g. a bank) or raised from a group of 10 or more non-associated persons.

These proposals — which would also require ‘catch-up’ payments for existing arrangements — could have a material impact on New Zealand subsidiary funding costs.

Checklist for debt funding

- The use of local bank debt may avoid transfer pricing problems and should obviate the requirement to withhold tax from interest payments.

- Holding company tax losses not used in the current year may be carried forward and offset against a group company’s future profits, subject to shareholder continuity and commonality rules.

- The purchaser should consider whether the level of profits would enable tax relief for interest payments to be effective.

- A tax deduction may be available at higher rates in other territories.

- WHT of 15, 10, or 5 percent or, in some cases, 2 percent (under AIL) applies on interest payments to non-New Zealand entities.

Equity

Dividends and certain bonus share issues are included in taxable income. Payments of dividends are not deductible. Tax assessed on a dividend may be offset by any imputation credits attached to the dividend of the payer company. There are two main exemptions to the taxability of dividends for companies. These apply when:

- both the payer and recipient company are in a wholly owned group (i.e. same ultimate ownership)

- dividends are received from offshore companies (subject to certain minor exceptions).

The income tax exemption for foreign dividends has applied for income years beginning on or after 1 July 2009 (aligned to the start date of New Zealand’s current controlled foreign company (CFC) regime). Before the exemption was introduced, a ‘foreign dividend withholding payment’ was required to be made by a New Zealand company on receipt of a foreign dividend.

Withholding tax on dividend distributions and methods to reduce or eliminate it

WHT is generally imposed on dividend payments between New Zealand residents (as described earlier). For non-resident shareholders, dividends are subject to NRWT at 15 percent, where fully imputed.

The domestic rate of NRWT payable is 0 percent where a dividend is fully imputed and a non-resident investor holds a 10 percent or greater voting interest in the company (or where the shareholding is less than 10 percent but the applicable post-treaty WHT rate on the dividend is less than 15 percent; New Zealand currently has no treaties where this is the case).

For non-resident investors with shareholdings of less than 10 percent, the 15 percent WHT rate on fully imputed dividends can be relieved under the FITC regime, which eliminates the NRWT by granting the dividend-paying company a credit against its own income tax liability where the company also pays a supplementary dividend (equal to the overall NRWT charge) to the non-resident.

A 30 percent NRWT rate applies to unimputed dividends, but most tax treaties limit this to 15 percent or lower in the case of recently renegotiated treaties.

Selection of a favorable tax treaty jurisdiction for the establishment of a non-resident shareholder may be considered to reduce or eliminate this tax. The purchaser should be aware of the increased international focus on BEPs and the use of tax treaties to obtain tax advantages.

Accordingly, New Zealand’s new tax treaties contain explicit anti-treaty shopping provisions (i.e. limitation on benefits clauses and beneficial ownership requirements). This is the case with the recently renegotiated treaties with Australia, the United States, Singapore and Hong Kong due to their lower WHT rates.

Corporate migration

A New Zealand-incorporated company can transfer its incorporation from the New Zealand Companies’ Register and become registered on an overseas companies register. Such a company is no longer considered to be incorporated in New Zealand and, provided the other tests for tax residence are not met, becomes a non-resident for New Zealand tax purposes. This process is known as ‘corporate migration’.

A corporate migration is treated as a deemed liquidation of all assets of the company followed by a deemed distribution of the net proceeds. Income tax consequences, such as depreciation clawback, arise and NRWT obligations are imposed on the deemed distribution to the extent it exceeds a return of capital for tax purposes. The amount subject to NRWT typically includes the distribution of retained earnings and, for shareholders owning 20 percent or more of the liquidating company, capital reserves.

The WHT cost may be reduced by attaching imputation credits to the deemed dividend distribution (or under New Zealand’s tax treaty).

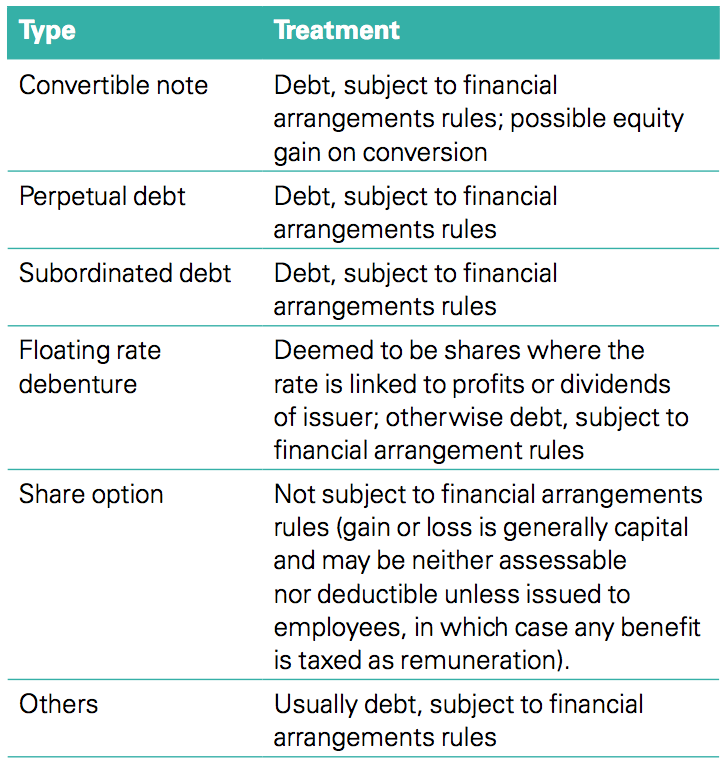

Hybrids

Hybrid instruments (with the exception of options over shares) are deemed to be either shares (treated as equity) or debt (subject to the financial arrangements rules). Various hybrid instruments and structures potentially offer an interest deduction for the borrower with no income pick-up for the lender.

However, the recent success of the IRD in challenging the application of certain hybrid instruments under tax avoidance legislation has called into question the validity of hybrid instruments in certain circumstances, particularly where they confer a tax advantage with little or no economic risk to the taxpayer. This is also an area of concern under BEPS.

The New Zealand government has enacted legislation to deny an interest deduction where a debt instrument is issued stapled to a share. The concern it addresses relates to M&A activity, where stapled debt instruments have featured prominently as part of capital-raising efforts.

The amendments treat such instruments as equity for tax purposes (thereby effectively denying an interest deduction to the issuer). The change applies to all stapled debt instruments issued on or after 25 February 2008.

KPMG in New Zealand recommends obtaining specialist advice where such financing techniques are contemplated or are already in place.

The following is a list of common types of instruments and their treatment for tax purposes.

Discounted securities

Interest deductions are determined on an accrual basis over the term of the security. The applicable spreading method for recognition of the deduction is prescribed under the financial arrangements rules.

Deferred settlement

Where settlement is to be deferred, the financial arrangements rules may deem a part of the purchase price to be interest payable to the vendor.

This may be avoided by having the sale and purchase agreement specifically state whether interest is payable and, if so, the terms. This generally gives rise to a ‘lowest price clause’ in the sale and purchase agreement, stating that no interest is payable due to the deferred settlement. However, from the purchaser’s perspective, it may be desirable to have an element of the purchase price deemed to be interest payable to the vendor, as this may give rise to a deduction of the portion of the purchase price deemed to be interest.

Recent legislation changed the tax treatment of deferred property settlements denominated in a foreign currency as of the 2014–2015 income year (or earlier income years if elected by the taxpayer). As a result, purchasers using International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are required to follow their accounting treatment to recognize interest and/or foreign currency fluctuations arising in relation to the agreement.

Consolidated income tax group

Two or more companies that are members of a wholly owned group of companies may elect to form a consolidated group for taxation purposes. The effect of this election is that the companies are treated for income tax purposes as if they were one company. The group only has to file one income tax return and receives one tax assessment. However, all members of the group become jointly and severally liable for the entire group’s taxation liabilities. Approval may be sought from the IRD for one or more group companies to be relieved from joint and several liability in certain circumstances.

Other considerations

Intragroup transactions are disregarded for income tax purposes, although asset transfers result in deferred income tax liabilities. For a consolidated group, the income tax impact of intercompany asset transfers arises when the company that was the recipient of any asset leaves the consolidated group while still holding the property acquired, or when the asset itself is sold.

The main advantage of consolidation is that assets can be transferred at tax book value between consolidated group companies. Companies that are not part of such a regime must transfer assets at market value, realizing a loss or gain on the transaction for income tax purposes.

KPMG in New Zealand notes that this only consolidates income tax. Other taxes still need to be reported individually (unless the relevant tax (e.g. GST) allows grouping under its rules).

Concerns of the seller

When a purchase of assets is contemplated, as opposed to the purchase of shares, the vendor’s main concern is likely to be the recovery of tax-depreciation (assessable income) if the assets are sold for more than their book value for tax purposes.

Company law and accounting

Company law

The Companies Act 1993 prescribes how New Zealand companies may be formed, operated, reorganized and dissolved.

Merger

A merger usually involves the formation of a new holding company to acquire the shares of the parties to the merger and is usually achieved by issuing shares in the new company to the shareholders of the merging companies. Once this step is completed, the new company may have the old companies wound up and their assets distributed to the new company. Certain companies (i.e. ‘Code Companies’, as defined) must comply with the obligations of the Takeovers Code.

Acquisition

A takeover involving large, publicly listed companies may be achieved by the bidder offering cash, shares or a mixture of the two. Acquisitions involving smaller or privately owned companies are accomplished in a variety of ways and may involve the acquisition of either the shares in the target company or its assets. Again, Code Companies need to comply with the obligations of the Takeovers Code.

Amalgamation

An amalgamation is a statutory reorganization under New Zealand law. Concessionary tax rules facilitate amalgamations. In New Zealand, an amalgamation involves a transfer of the business and assets of one or more companies to either a new company or an existing company.

All amalgamating companies cease to exist on amalgamation (unless one of them becomes the amalgamated company), with the new amalgamated company becoming entitled to and responsible for all the rights and obligations of the amalgamating companies.

Accounting

Consideration should be given to any potential impact that IFRS may have on asset valuations and thus on how the deal should be structured. For example, is any goodwill on acquisition recorded as an asset in a New Zealand entity’s financial statements, and is there a potential impact on asset valuations for thin capitalization purposes?

Group relief/consolidation

Companies form a group for taxation purposes where at least 66 percent commonality of shareholding exists. The profits of one group company can be offset against the losses of another by the profit company making a payment to the loss company. Alternatively, a loss company can make an irrevocable election directly to offset its losses against the profits of a group profit company. Companies must be members of the group from the commencement of the year of loss until the end of the year the loss is offset.

There is no requirement to form a consolidated tax group in order to offset losses.

Transfer pricing

New Zealand has a comprehensive transfer pricing regime based on the OECD’s transfer pricing guidelines.

Generally, the transfer pricing regime applies with respect to cross-border transactions between related parties that are not at an arm’s length price (e.g. the New Zealand company does not receive adequate compensation from, or is overcharged by, the foreign parent/group company). Two companies are generally considered related for transfer pricing purposes where there is a group of persons with voting (or market value) interests of 50 percent or more in both companies.

Where transaction prices are found not to be at arm’s length, the transfer pricing rules enable the IRD to reassess a taxpayer’s income to ensure that New Zealand’s tax base is not eroded. In recent years, the rates of interest charged on intercompany lending have become a particular area of increased focus by the IRD.

Dual residency

New Zealand has an anti-avoidance rule that prevents a dual resident company from offsetting its losses against the profits of another company.

Foreign investments of a local target company

New Zealand’s CFC regime attributes the income of an offshore subsidiary to its New Zealand-resident shareholder in certain circumstances.

A company is regarded as a CFC for New Zealand purposes where the New Zealand-resident shareholder meets certain control tests (i.e. one shareholder holds 40 percent or more of the voting interest or five or fewer shareholders collectively hold more than 50 percent voting interests).

An ‘active’ income exemption applies to profits from a CFC, under which:

- income must only be attributed where 5 percent or more of the CFC’s income is ‘passive’ (e.g. from dividends, rents, interest, royalties and other financial income; only passive income is attributed if the test is failed)

- dividends from CFCs are exempt

- there is a general exemption from the active income test where the CFC is resident and liable to tax in Australia

- outbound thin capitalization rules apply.

Comparison of asset and share purchases

Advantages of asset purchases

- The purchase price (or a proportion) can be depreciated or amortized for tax purposes (but not goodwill).

- A deduction is gained for trading stock purchased.

- No previous liabilities of the company are inherited.

- No future tax liability on retained earnings is acquired.

- Possible to acquire only part of a business.

- Greater flexibility in funding options.

- Profitable operations can be absorbed by loss companies in the acquirer’s group, thereby effectively gaining the ability to use the losses.

Disadvantages of asset purchases

- Possible need to renegotiate supply, employment and technology agreements.

- A higher capital outlay is usually involved (unless debts of the business are also assumed).

- May be unattractive to the vendor, thereby increasing the price.

- Accounting profits may be affected by the creation of acquisition goodwill.

- GST may apply to the purchase price, giving rise to a possible cash flow cost, even where the purchaser can claim the GST.

Advantages of share purchases

- Lower capital outlay (purchase of net assets only).

- Likely to be more attractive to the vendor, which should be reflected in the price.

- May gain benefit of existing supply or technology contracts.

Disadvantage of share purchases

- Acquire potential unrealized tax liability for depreciation recovery on the difference between market and tax book value of assets (if deferred tax accounting is applied, this should be reflected in the net assets acquired).

- Subject to warranties and indemnities, purchaser could acquire historical tax and other risks of the company.

- Liable for any claims on or previous liabilities of the entity.

- No deduction for the purchase price.

- Acquire tax liability on retained earnings that are ultimately distributed to shareholders.

- Less flexibility in funding options.

- Losses incurred by any companies in the acquirer’s group in the target’s pre-acquisition years cannot be offset against any profits made by the target company.