By Frank Herrmann, Moritz Dressel – Deloitte

Executive summary

Life science companies have adopted a multi-track approach to cope with the current and anticipated drop in sales revenue, including cutting costs and staff; expanding business in emerging markets; recalibrating business models and research priorities; using real-world evidence and emphasising a product’s clinical, safety and economic impact to articulate their value proposition. Next to classic mergers and acquisitions (M&A) Strategic Alliances have proven to be a viable alternative in coping with these challenges.

As the drop in sales and revenues results from a plethora of challenges, from patent cliff to regulatory changes, Deloitte believes that M&As are potentially not the only course of action. Actively engaging in alliances is a viable alternative to M&As to adopt a more network-oriented business. However, this is easier said than done and establishing successful alliances is a complex process.

As the drop in sales and revenues results from a plethora of challenges, from patent cliff to regulatory changes, Deloitte believes that M&As are potentially not the only course of action. Actively engaging in alliances is a viable alternative to M&As to adopt a more network-oriented business. However, this is easier said than done and establishing successful alliances is a complex process.

Survey participants acknowledge the benefit of strategic alliances to face current industry challenges; as one of the industry leaders stated: “We prefer M&As if the conditions allow but engaging in alliances is the best alternative.” Surprisingly, alliance activity correlates positively with sales and R&D intensity, which contradicts the view that small entities leverage alliances as a product development or commercialisation vehicle. Furthermore, results show that the industry does not yet maximise the full potential of alliances as they mostly engage in non-equity alliances with low investments.

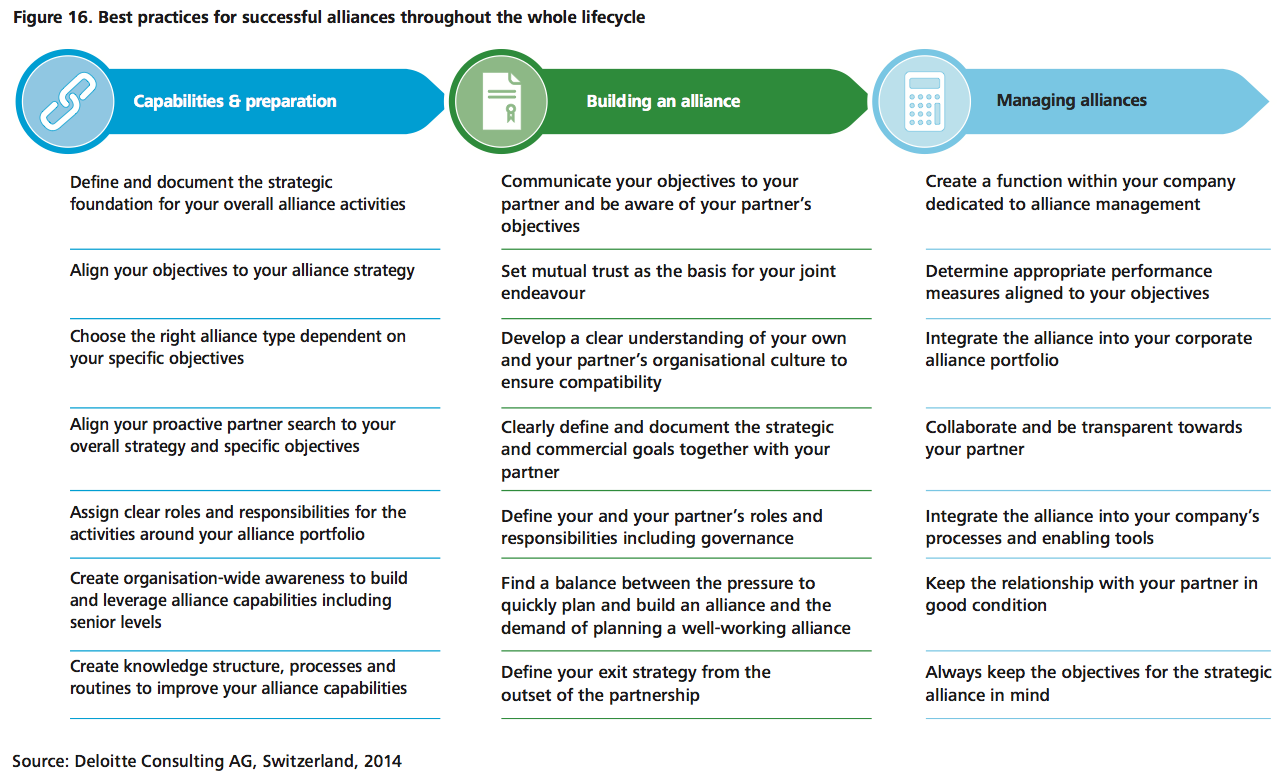

The study shows that most of the participating companies are not yet fully prepared for alliances which might be either the consequence or the origin of the prevalence of low-risk approaches. Issues such as a lack of: a documented strategy, dedicated resources and performance measures and a prolonged alliance formation phase due to lack of transparency and ineffective internal decision-making processes, were highlighted. However, most companies seem prepared for the termination of the alliance, an inherent part of the lifecycle, by having an exit strategy in place. As companies navigate the alliance building process, new challenges arise when they progress to alliance management. Organisational or “people” aspects, such as each party’s contribution to governance and management control, rather than commercial aspects seem to be the most challenging. Mitigating such potentially contentious issues has been identified as a key success factor with mutual trust being the most important element.

Nearly all respondents expect an increase in the number of alliances in the life science industry, especially in emerging markets such as China, India and Latin America. In terms of types of alliance, equity alliances were thought to be the most likely to increase in number. Companies will need to adapt their alliance capabilities to cope with these somewhat new alliances which require a higher degree of integration. Companies that can demonstrate a high degree of alliance readiness will most likely become the most sought after by potential partners. Hence, professional alliance capabilities will be a crucial determinant of future life science business failure or success.

1. Context

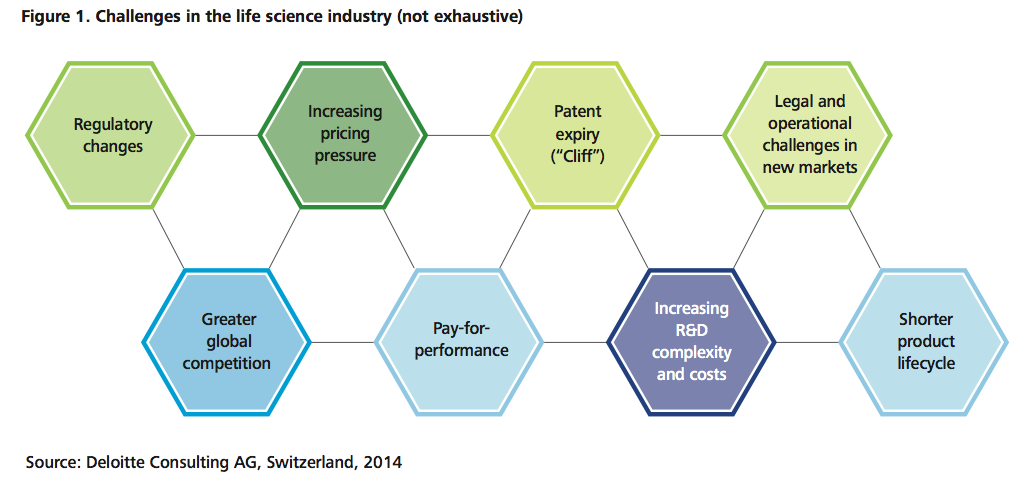

The life science industry is facing challenges that fundamentally question traditional business models (Figure 1). The set of challenges is complex and affects virtually all business critical areas.

Patent expiry

Over recent years, the life science industry has been increasingly exposed to what has been termed the patent cliff. When a best-selling blockbuster drug loses its patent protection, the influx of cheaper generic equivalents puts revenue and profitability under enormous pressure. The rate of erosion of branded drug sales by generics depends on the product and the corresponding generic approval process; erosion may occur more or less rapidly. Revenues lost due to patent expiry are not being replaced by revenues generated from new product launches, as few life science companies have been able to maintain a sufficient late-stage product development pipeline. Increasingly, internal research and development (R&D) operations are struggling to deliver promising new drug candidates. R&D costs among the big life science companies have continued to increase over time, while terminations from late stage pipelines have remained static.

Additionally, due to austere market conditions and increasing pressure on payer budgets, the likely revenue potential of new product launches has declined. The industry is also feeling the negative impact of stricter product approval processes, requiring, for example, more extensive clinical trials with greater patient samples and longer observation periods. Deloitte estimates that the internal rate of return from R&D has decreased to below five per cent and the average cost of bringing an asset to market has risen to $1.3 billion in 2013. Quite literally, for many companies, this is too big a pill to swallow.

Competition with market exclusivity

There has also been a substantial increase in industry competition with market exclusivity – the time for which a newly launched drug is protected from copy products – being continuously shortened. Historically, new drugs were followed by competing products after only a period of several years. Nowadays, there is typically a gap of merely few months between first and second launches in a product class. Obviously, the potential return from new product launches is becoming substantially undermined.

Regulatory changes

Regulatory oversight and consumer protection evolved and might evolve even further in response to increasing consumer expectations, industry growth and innovation provoking unintended consequences, and changing government mandates. Regulatory changes include:

• more stringent quality measures and new drug approval regulations are implemented

• increasing scrutiny of manufacturing processes to ensure product safety, restrictions to support domestic manufacturers, such as high import tariffs

• new legislation such as the pharmacovigilance legislation from the European Medicines Agency which significantly increases data provision requirements and the burden on regulatory operations and systems.

This market intervention greatly affects the existing profit base of life science companies in mature markets and impedes profit growth in emerging markets.

Changing market dynamics

As new types of companies enter and compete for market share market dynamics are changing. This is particularly evident in the business of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs – medicines sold directly to a consumer without prescription from a healthcare professional. Regulatory shifts towards more liberalisation are increasing and easing consumer access to OTC medicines. Fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies benefit from this trend in particular. Traditionally more focused on physicians and payers, life science companies are a step behind FMCG companies when it comes to consumer strategy. The latter’s very consumer driven nature and competence in branding, advertising and segment differentiation stand in stark contrast to the typically operational focus on R&D efficiencies in the life science industry. These new entrants are positioned to exploit their traditionally strong consumer focus and put further pressure on life science organisations. Where there was previously limited consumer interaction, a shift in focus is required to ensure increasing consideration of the consumer when packaging, labelling, and marketing life science products.

Potential of emerging markets

There is also a geographic element that requires attention from industry incumbents. Emerging markets have experienced rapid growth in recent years and, although growth forecasts have been downgraded recently, they are still forecast to continue to outperform other regions over the next few years. An increasing level of affluence in emerging markets provides attractive new opportunities for all sectors of the life science industry. Tapping into these opportunities, however, is likely to pose additional challenges from both a legal and operational perspective. Some governments require foreign companies to engage with local parties, while in other cases it is simply not feasible to successfully launch and sell products without a capable salesforce in place.

To cope with the plethora of increasing challenges, there are a number of options industry players are likely to consider, most notably M&As. The industry has experienced a number of mega-M&A’s such as Bayer Schering (2006), J&J Pfizer OTC (2007), Pfizer Wyeth (2009) and some recent activities like Novartis, GSK or Merck and Bayer. However, financing conditions have changed over the course of the last decade and, while not being as critical as during the peak of the global financial crisis which started in 2008, financing is unlikely to be infinite. Deloitte believes that M&As are unlikely to be the sole answer to address the ever- increasing complexity and uncertainty associated with R&D innovations and market access in the life sciences industry. Strategic alliances present a viable and less drastic approach to complement traditional M&A. The recent announcement of Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline to combine their consumer business divisions in a joint venture supports this view.

Deloitte defines alliances as third party business relationships that share risks and rewards through enhanced collaboration between otherwise independent entities. Alliances can exist in many different forms depending on the degree of integration and level of control. The focus of this report is strategic alliances that include:

- Joint Ventures

- Equity Alliances

- Non-Equity Alliances.

Important alternative contractual agreements such as licensing and cross-licensing as well as other informal collaborations were excluded from this analysis (Figure 2).

Deloitte defines alliances as third party business relationships that share risks and rewards through enhanced collaboration between otherwise independent entities.

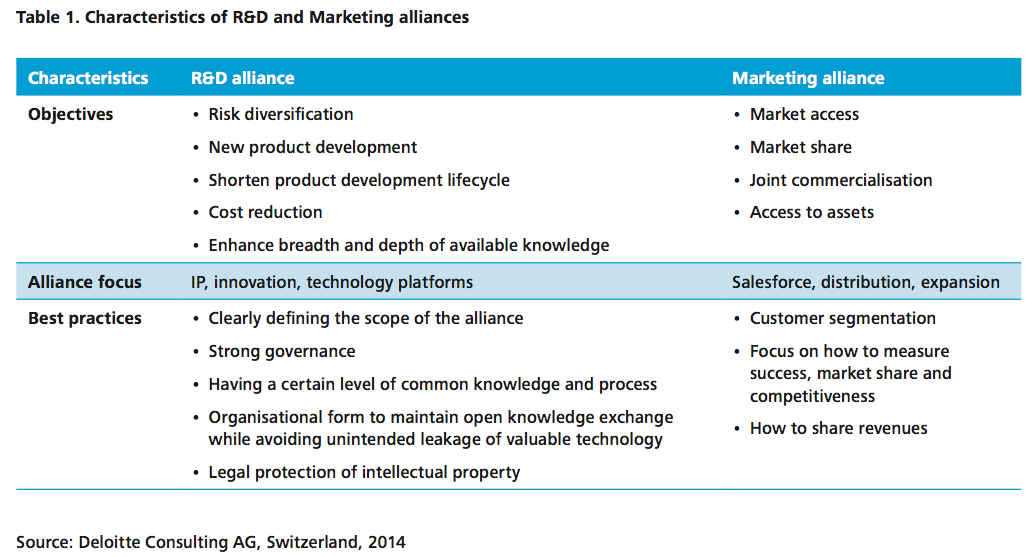

Depending on the objectives and the challenges faced, a company can engage in different types of alliances. As summarised in Table 1, companies willing to develop new products or increase market share might want to consider looking for a partner in the field of R&D or marketing, respectively.

R&D alliances are likely to be a promising avenue for companies to maintain or improve their competitive advantage. This type of alliance enables companies to acquire knowledge about technologies, processes, products and business models. However, by combining the knowledge of two or more entities, the imminent danger of safeguarding intellectual property (IP) is a daily occurrence. The joint venture between Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline in the field of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) set up in 2009 is a good example; by creating a joint company and combining their R&D activities, product development was driven forward and the business became more economically viable.

2. Survey methodology

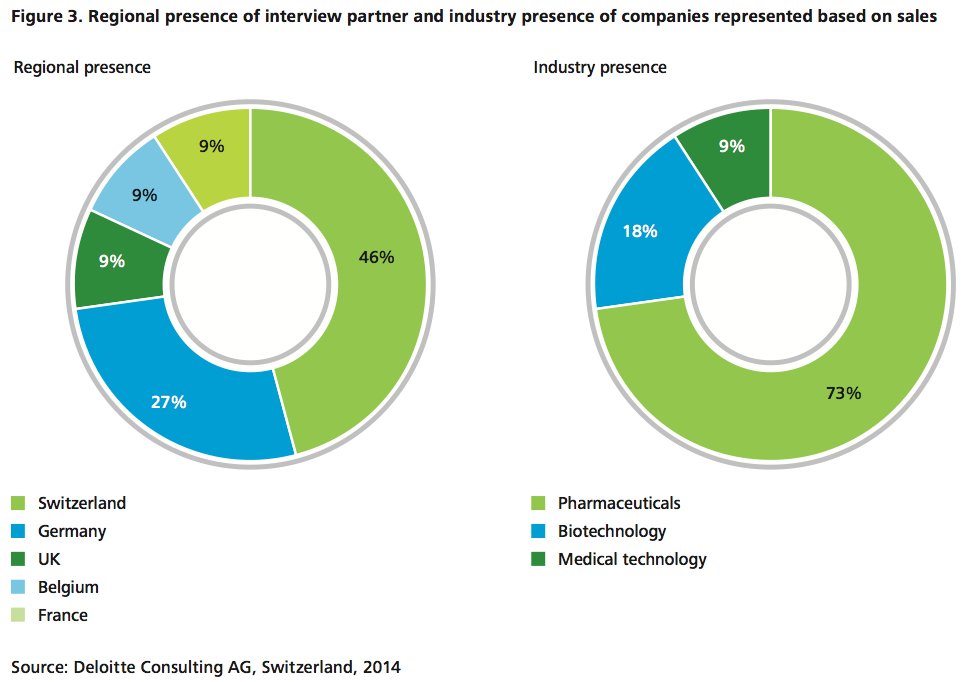

Research was conducted with various, senior life science industry leaders actively engaged in alliance functions. Job titles ranged from Head of Corporate Strategy to Head of Alliance Management. All respondents were based in Western Europe, with 46 per cent based in Switzerland and 27 per cent in Germany (Figure 3).

The companies represented fell into one of the three industry sub-sectors; pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, or medical devices classified according to their sales revenues per sector. Companies active in more than one sector were allocated to the sector which generated the highest proportion of sales.

The results of interviews were analysed and findings substantiated with previous research and extensive project experience. The number of responses per question varied, as some respondents chose not to respond to all questions. The report findings provide an analysis of:

- the perceived state of strategic alliances within the life science industry

- the overall alliance readiness of the industry

- a set of best practices that every company should consider including in their business development or alliance strategy toolkit.

Survey framework

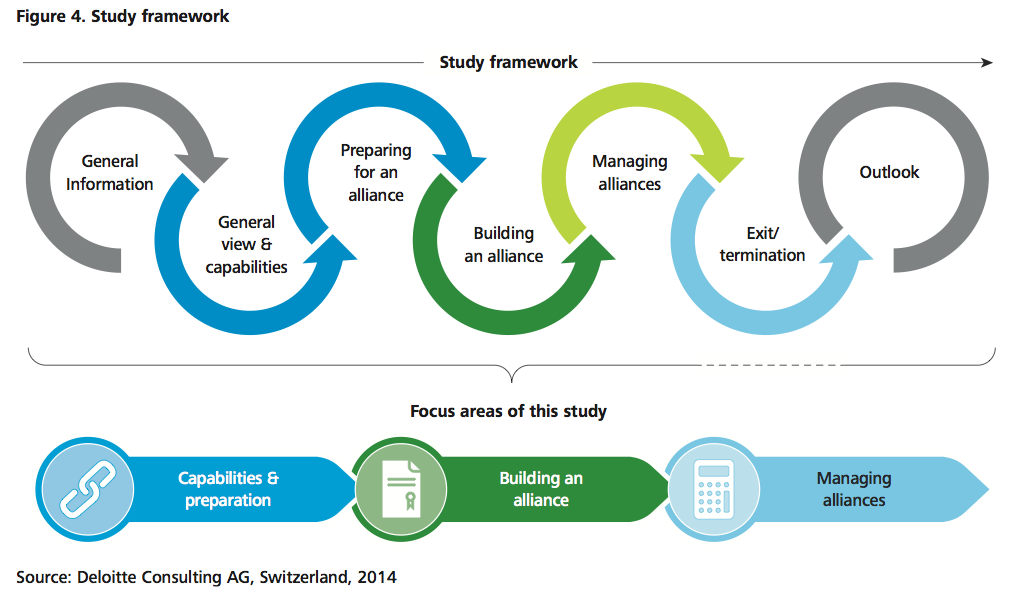

To provide a holistic view of strategic alliances in the life science industry, three key components along the alliance lifecycle were assessed (Figure 4):

- preparing for an alliance and alliance capabilities – to quantify current alliance activities, understand key objectives for alliance engagement and how alliances are initiated

- building an alliance – to capture current activities regarding early negotiation and eventual organisation design, including blueprinting

- managing alliances – to understand how companies manage their collective alliance portfolio, focussing on alliance governance activities.

The study concluded with a brief industry outlook by respondents articulating their view on the future of alliances in the life science industry, including identifying target geographies.

To provide a holistic view of strategic alliances in the life science industry, three key components along the alliance lifecycle were assessed.

3. Key findings

The most significant results of the study are summarised below:

1. Clear benefit for everyone

Respondents generally agreed that strategic alliances will continue, if not increase within the life science industry. However, the objectives motivating the creation of new alliances are wide and varied, can originate internally or externally, and are often specific to the challenges that the company faces. Internal drivers most prominently include new product development, risk diversification and cost reduction, while external drivers tend to be market access, joint commercialisation, and access to assets.

Respondents indicated that both objectives driven internally and externally are prominent and neither appears to have dominated until now (Figure 5). Looking to the future, there seems to be a marginal shift to alliances being driven by internal objectives. While joint commercialisation and market access remain important drivers, two internal drivers, new product development and risk diversification, clearly stand out as the two most important objectives for future alliances.

Deloitte believes that the increase in internal objectives is partly driven by the various challenges described in the previous section.

Besides knowing one’s own objectives for pursuing an alliance, Deloitte believes that having an understanding of the motivation of the partnering company is just as essential. The objectives of both potential partners should be considered when deciding on the type of alliance, whether, for example an R&D or a Marketing alliance is being considered.

2. Size matters

Even though all respondents clearly see the need for alliances, the study results show certain patterns based on sales and R&D intensity when considering who actually engages in alliances.

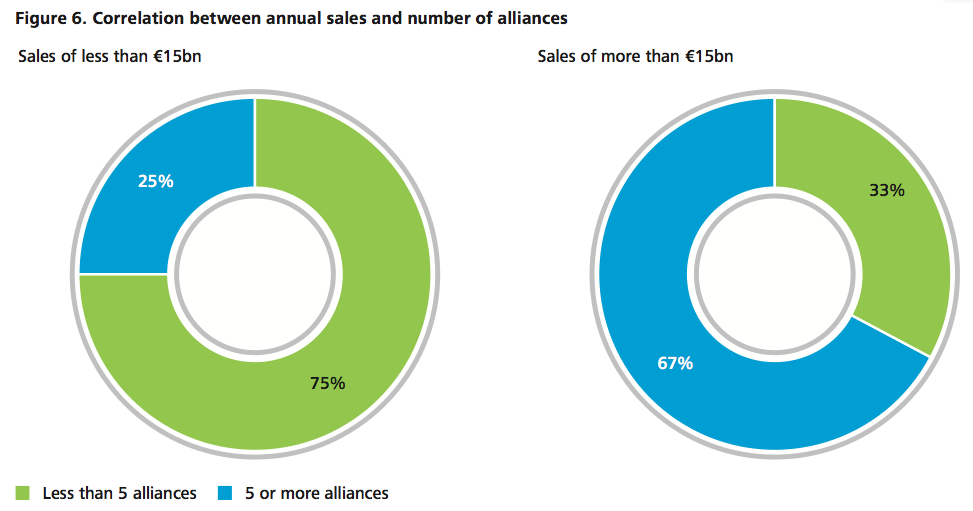

When total annual sales revenues are considered, larger entities seem to be using strategic alliances more readily than smaller companies. Smaller companies rarely engage in more than a handful of alliances: of those respondents working in larger entities with more than €15 billion of annual sales, 67 per cent indicated that they are engaged in more than five alliances (Figure 6). This compares with only 25 per cent of respondents employed in smaller organisations (with sales of less than €15 billion).

Since acquisitions are generally costly to undertake, Deloitte believes that smaller entities should consider strategic alliances not only to profit from the partner’s R&D capabilities but also for joint commercialisation.

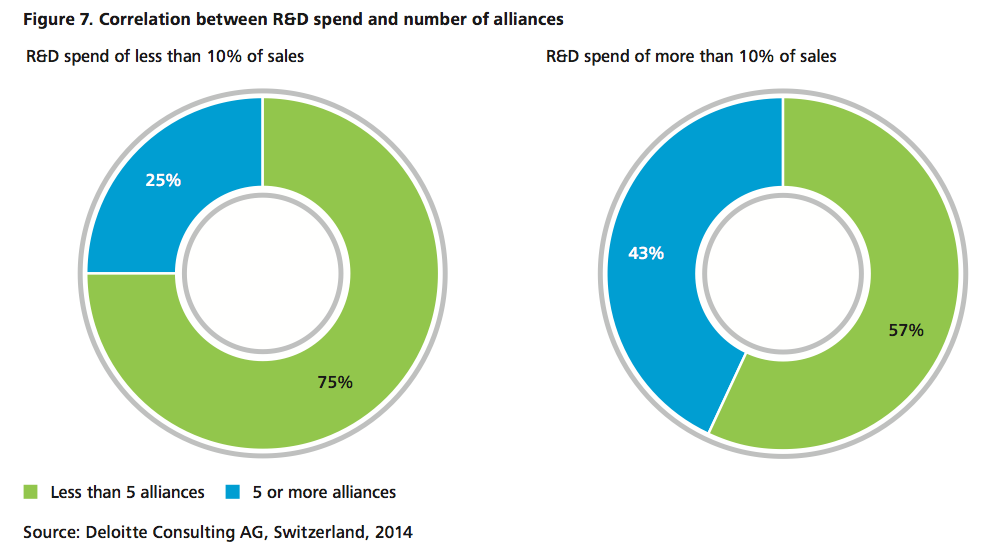

Strategic alliances appear to be a particularly attractive course of action for research-intensive industry players. When interrogating the dataset, research intensity, as measured by R&D spend versus annual sales, tends to be positively correlated with alliance activity (Figure 7). Almost half of those with an R&D:Sales ratio of more than ten per cent are engaged in more than five alliances. This compares to only 25 per cent for those with an R&D:Sales ratio below ten per cent.

3. Not yet fully leveraged

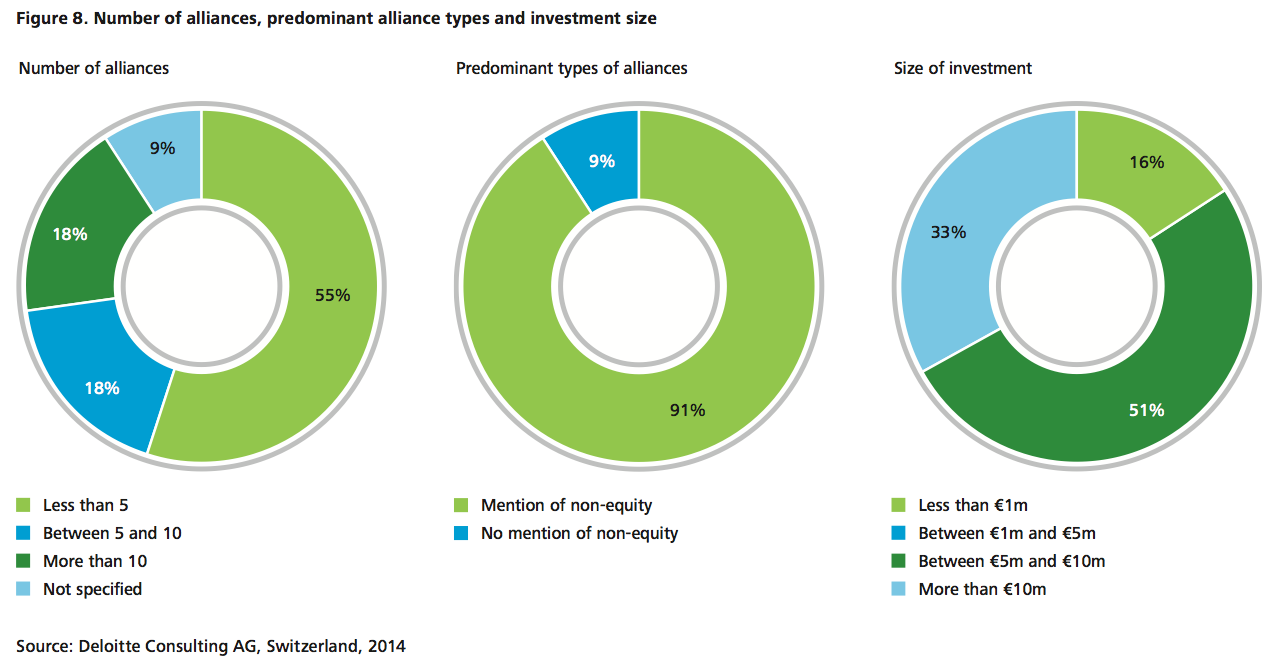

The study reveals that the current modus operandi appears to be one of minimal risk exposure and investment, the appetite for tighter integration with a partner seems relatively weak. This understanding is based on the typical number of alliances being managed, preferred alliance types, and the value of alliance investments being made (Figure 8).

The results show that the organisations represented in this study are engaged in a limited number of alliances; more than half of those surveyed reported to be engaged in less than five strategic alliances.

In terms of the type of alliance that organisations invest in, non-equity alliances predominate. A total of 91 per cent of respondents mentioned non-equity alliances as a commonly adopted approach. Joint ventures and equity alliances were mentioned to a significantly lesser degree.

Finally, the alliance relationship investment is a further indication of the relatively low commitment companies seek to make. Currently, intangible assets, such as intellectual property (IP), are the number one contribution and clearly reflective of the life science industry. More tangible commitments are less common, financial investments in particular appear to be rather limited in size. 67 per cent of the respondents who were able to specify their company’s average investment size estimated an average contribution of €10 million and below.

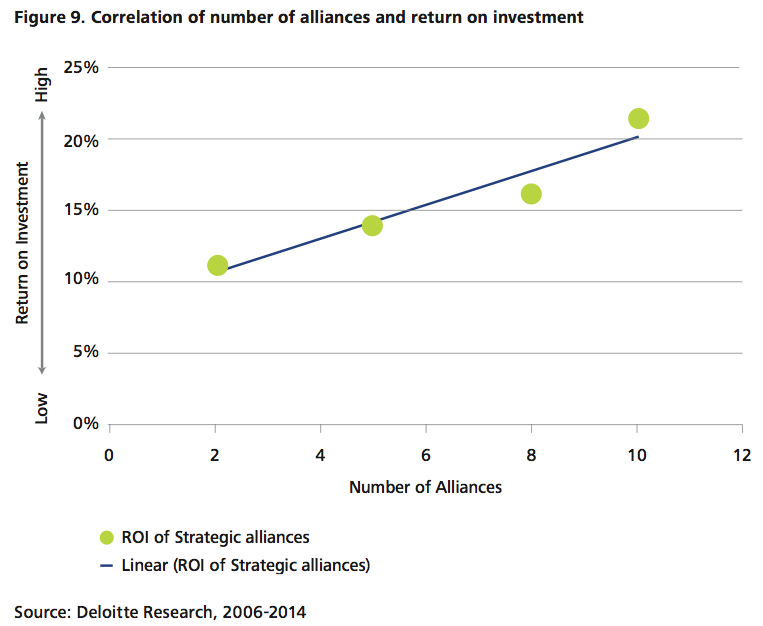

A high number of alliances and a large investment size are not the only criteria for success. However, the relatively low number of partners may contribute to a lower level of overall alliance management experience in the future. Research shows that alliance success, as measured as the average return on investment from alliances, is positively correlated with the number of partnerships one engages in (Figure 9). This is good news and a strong case in favour of alliance building as it is not just the soft factor of experience, but also hard, measurable facts that indicate the currently predominant approach to be less than ideal.

Currently there is a lack of adequate alliance setup and first-hand experience of alliance management, which will most likely only serve to inhibit the industry’s ability to capture the full value of strategic alliances. To realise the true potential of strategic alliances, an increase in number of alliance engagements as well as a higher commitment – be it financial or not – is required.

4. There are no shortcuts

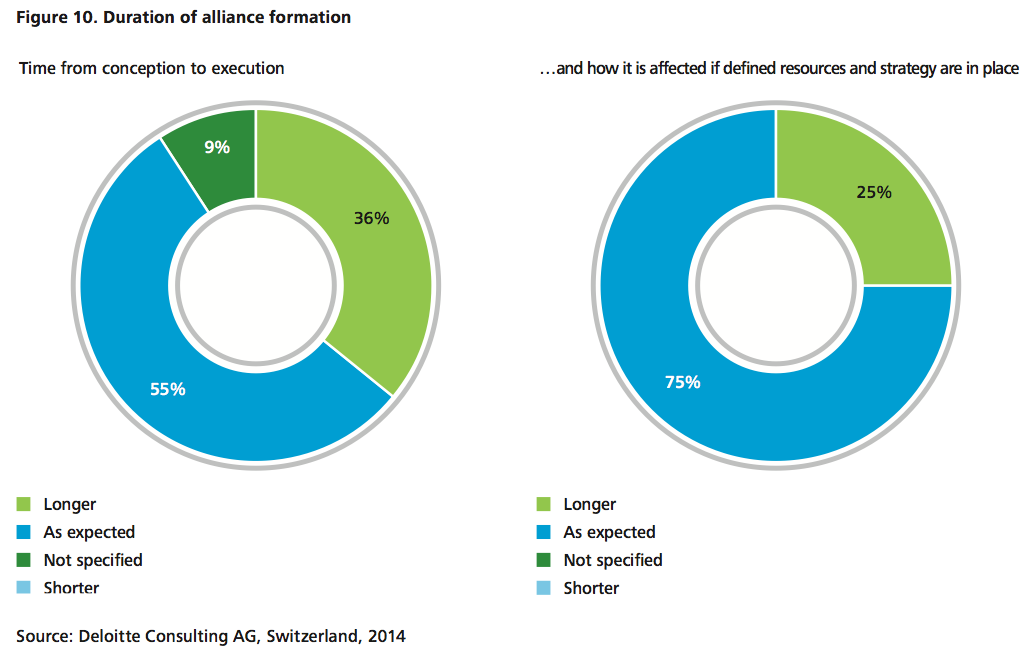

Taking an alliance from conception to execution appears to be a challenge and none of the respondents reported shorter than expected preparation time (Figure 10). While expectations are often met, just over a third of respondents reported that the time to set up an alliance takes longer than expected. Some respondents even stated that only few alliances survive the conception and negotiation phase with time being a crucial factor.

Respondents stated ineffective internal decision-making processes, several levels of iteration during negotiation and a lack of transparency regarding required information as inhibiting factors. In contrast, maintaining a degree of informality among key stakeholders and documented strategy regarding alliances were stated as positively affecting the duration from conception to execution. The survey results tend to support the latter enhancing factor. Only 25 per cent of those with resources and strategy in place, compared to 36 per cent of all respondents, take longer than expected for alliance formation. This may be a result of better implementation or more adequate expectation setting.

5. Good intentions are not enough

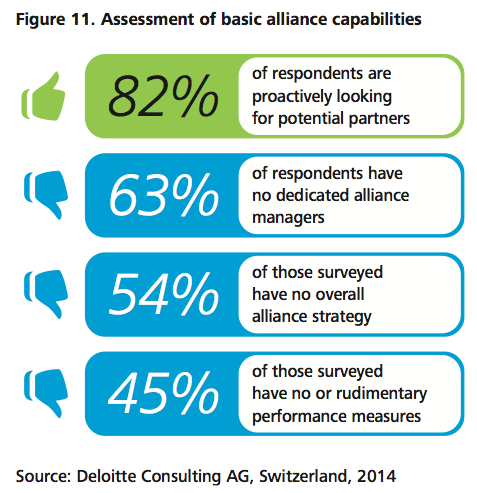

While the survey shows that most organisations have an appetite for alliances, they often lack the basic skills, competencies and processes to take full advantage of such opportunities (Figure 11). Often, the strategic foundation is only loosely defined and it comes as little surprise that only 46 per cent of those interviewed have one common, documented alliance strategy in place and 18 per cent have no documented alliance strategy at all. The remainder, a third, have some type of strategic framework in place, but these are typically embedded in single business units or divisions and are not shared across the whole organisation, thereby, risking an overall misalignment across the alliance portfolio. In addition without strategic objectives, the search for a potential partner cannot be effective, even if 82 per cent of the respondents proactively look for a partner. The search should be driven by the company’s strategy and not vice versa.

Looking at how alliances are being managed, the study shows that 63 per cent of the respondents do not have a dedicated alliance manager, nearly half of which could not even specify where alliance management was sitting from an organisational point of view. A strategic alliance needs dedicated support within both companies to drive all activities in the alliance lifecycle and, to ensure that the strategic objectives of both companies are pursued.

Industry practice for measuring the performance of alliances is rather poor; 45 per cent of respondents have no or rudimentary alliance performance measures in place and only a few are able to specify the exact return and the performance of their alliances. More often than not, respondents had to rely on gut feeling. Deloitte believes an overarching set of measures should be applied to evaluate and compare different alliances within the portfolio which could be further supported through alliance-specific metrics. At the moment, both are largely non-existent and it remains a mystery if and how alliance success is actually being determined.

Effective alliance management requires appropriate organisational structures and a well-defined strategic foundation. Alliance management is a proactive process; it depends on individuals continually driving the agenda and the implementation of relevant performance management metrics to monitor progress. Both the survey respondents and Deloitte’s experience from client work indicate that the industry can substantially improve its strategic alliance formation and management by:

- defining a strategic direction

- clearly assigning roles and responsibilities throughout the whole alliance lifecycle to ensure leadership continuity

- defining and measuring performance metrics

6. Not built to last

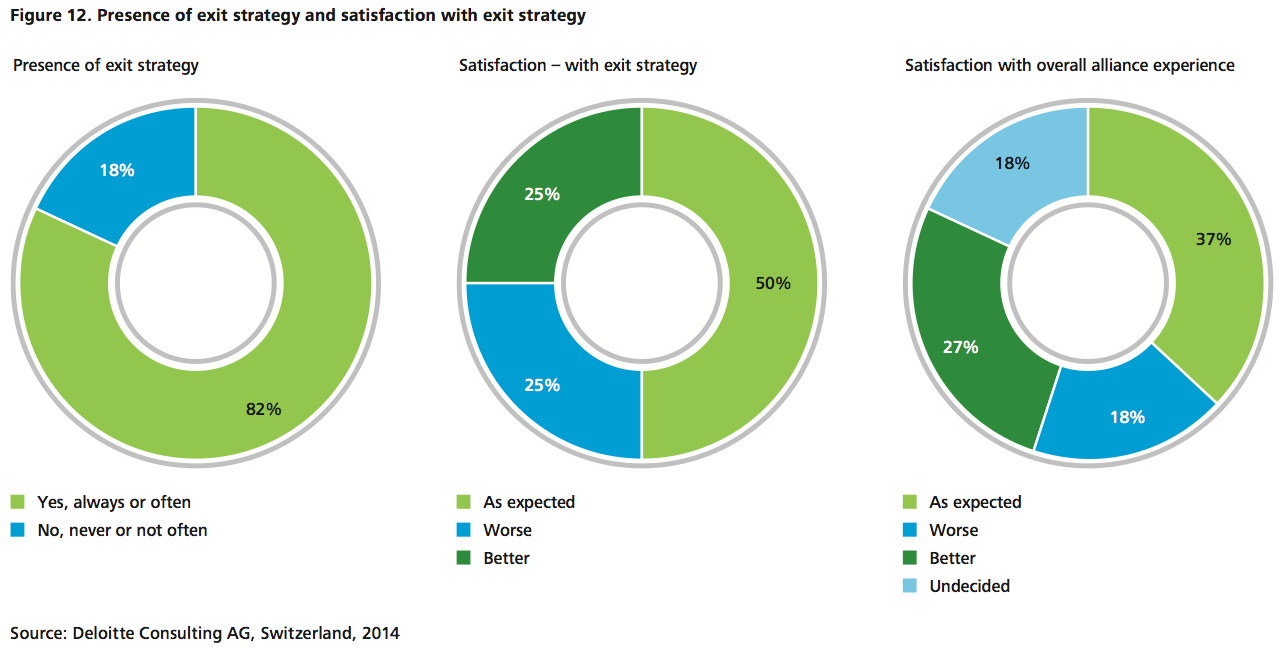

There are definitely methods that can be employed to ensure alliances are being managed successfully. With the right setup, as mentioned in the previous section, the groundwork can be laid for a successful alliance. From a strategic perspective, there is a lot that Deloitte recommends to do even before first negotiations have started; having a clear alliance strategy in place helps greatly in identifying the right set of potential alliance partners. Likewise, exit strategies can be prepared independent of one’s partner. In fact, a basic framework of key criteria to consider when devising an alliance-specific exit strategy should be readily available at any point in time; indeed 82 per cent of respondents are well prepared for a possible separation by having an exit strategy in place (Figure 12).

This does not mean that the study participants have a pessimistic view of the alliance but rather that they are fully aware that alliances have a natural life span. A well-defined exit strategy is essential to benefit fully from the alliance without facing any uncertainty throughout the lifecycle.

Nevertheless, among the respondents, having an exit strategy does not seem to increase satisfaction regarding the company’s overall alliance experience. The level of satisfaction with an exit strategy (50 per cent of respondents) is comparable to the satisfaction level of alliances in general among all study participants. A possible explanation is that the full benefit of having an effective exit strategy is likely to be reaped only in the event of alliance termination.

7. People over commercial

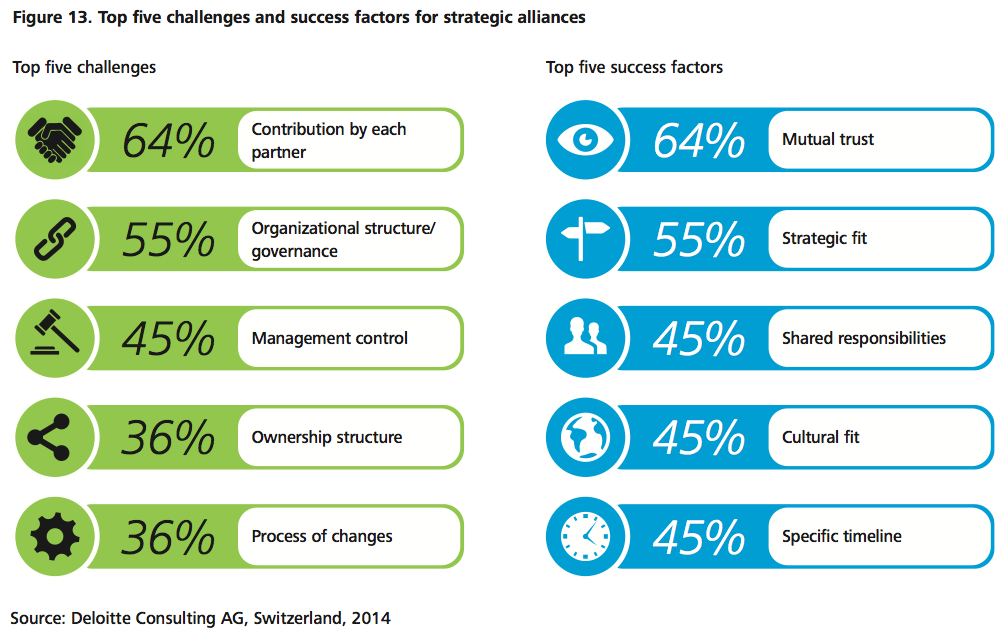

This study has helped to shed light on the key challenges faced by the life sciences industry when managing alliances. Respondents also reflected on the success factors they perceived as helping to make alliances work. These success factors appear to align closely with the challenges encountered (Figure 13).

Respondents indicated that disagreements around “people” aspects of alliances, more precisely equal contribution by each partner, organisational structure, governance and management control, were the primary challenges they face. Interestingly, these most important challenges, as well as those around ownership structure, faced by 45 per cent of the respondents, can by and large be settled or agreed during early negotiations prior to alliance formation. Processes for potential changes should also be discussed early in the relationship, however experience shows that this is rarely the case.

Deloitte believes that companies need to find ways to balance the time pressures they face in terms of planning and building a new alliance with the need to ensure that everything is in place to make the alliance a success.

Although this might demand significant time and resources, it increases everyone’s comfort during the alliance’s lifecycle. While respondents ranked equal contribution from both partners as a key challenge, performance measures appear to be of less importance. Holding each partner accountable on the basis of clearly defined, quantifiable targets goes a long way towards making alliance management an objective, less contentious undertaking.

Mitigation of potentially contentious subjects between partners has been described as a key success factor. Broadly speaking, the success factors fall into three categories: strategy, people, and alliance, with “people” being the most important aspect for alliance success.

Deloitte believes firstly, as alliances are dependent on managing relationships effectively, the people dimension is critically important, a belief which is supported by the survey findings. The presence of mutual trust was mentioned as the single most important success factor by 64 per cent of respondents. Cultural fit was also deemed important but by fewer (45 per cent) respondents. These factors clearly help to eliminate the number one challenge of equal contribution.

Secondly, the strategy dimension is important as it lays the foundation for the relationship: Respondents deemed strategic fit between the parties a critical success factor; it was selected by more than half of the respondents and ranked second in terms of most important success factor in making alliances work. Clearly documenting and communicating the strategy is the first step towards exploiting the potential of strategic fit as a success factor.

Finally, as previously mentioned, alliance design contains all those aspects which should be agreed on prior to the formation of the alliance. As part of an initial blueprint, both companies should come to a common understanding of the overall governance and organisational structure, their responsibilities and performance objectives. Similarly, there should be an agreed timeline, i.e. a clearly defined implementation roadmap which all parties sign up to and work towards.

8. More of it – everywhere

In the future, 82 per cent of respondents expect an increase in overall strategic alliance activity. The remaining 18 per cent anticipate that current levels of activity will continue. While this generally applies to all regions worldwide, respondents highlighted emerging markets as the key geography for strategic alliance activity. China and India, as well as Latin America are on the agenda of most respondents in line with growth forecasts for these geographies which indicate strong market growth projections (Figure 14). In these large emerging markets, strategic alliances address the challenge of establishing effective operations. Other parts of Asia appear to be less of a target area for alliance building partly driven by a smaller market volume. Besides emerging economies, North America remains an attractive market for many life science companies and an important region for alliance building.

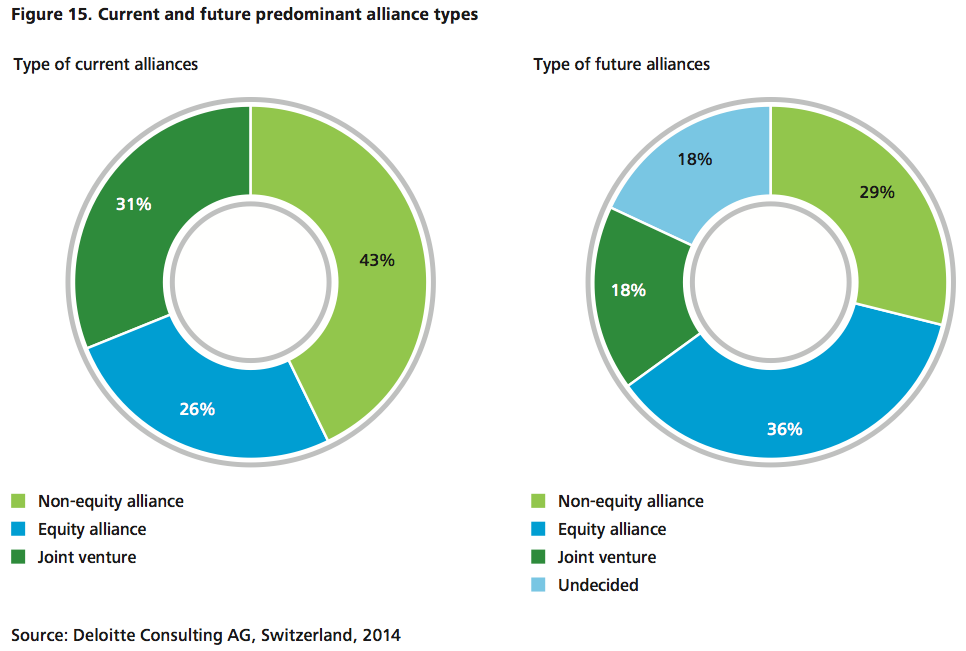

With respect to the types of alliances, respondents indicated a slight preference towards stronger integration. Whereas non-equity alliances are currently the most prominent form of partnership based on the interviews, the industry will see an increasing number of equity alliances in the future (Figure 15).

As both trends, importance of equity alliances and alliances in emerging markets, imply further challenges such as increased financial risks or risks of sharing intellectual property, basic alliance capabilities and a good preparation including alliance strategy, defined alliance management and clear objectives are even more essential for success.

4. Conclusion and best practices

It is clear to the life science industry and its commentators that traditional business approaches are unlikely to meet future challenges:

- delivery models need to be refined

- regulatory pressures need to be accommodated

- global competition is increasing

- R&D budgets are tightening as R&D cost per asset increases

The respondents interviewed overwhelmingly agree that there is a need to increase their engagement in strategic alliances. The research also revealed that the lack of a basic foundation, including clear strategy, assigned roles and responsibilities, and transparent communication, currently inhibits alliance activities in the life sciences industry.

Another prerequisite to fully capture the benefits from the network of alliances is a change in perspective of one’s own organisation and how this is embedded in the wider industry.

To achieve long-term alliance success, companies should start looking beyond their home turf and actively manage the entire scope of their third party relationships. A clearly defined portfolio management approach ensures greater alignment between existing alliances, which may have been established in separate business units, but is also subject to distinctive management challenges. Applying a consistent set of management criteria across the alliances portfolio is critical for placing companies on an upward trajectory in terms of alliance success.

How, then, should one go about the actual implementation of these best practices? As with every improvement, it starts from honest self-awareness: Understanding the perceived and actual strengths helps to consciously address the company’s main areas for improvements with a coordinated approach. Deloitte has developed a set of tools for alliance practitioners to self-assess their maturity, determine current gaps and define the next steps to reach their target as explained in more detail in the following section.

5. Selected Deloitte tools for alliances

Maturity assessment

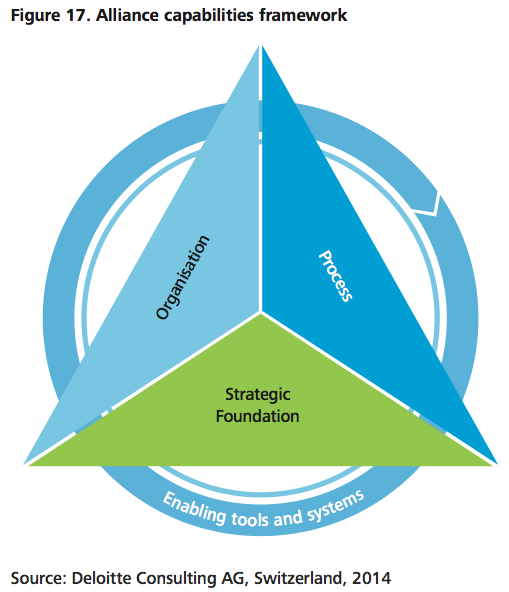

An initial self-assessment can and should be further substantiated by means of a structured Alliance Readiness Assessment. Such structured evaluation informs an organisation’s alliance capabilities in a systematic way, helps determine its current state and lays the foundation for a desirable, as well as realistic, target state. Dimensions covering strategic setup, people, systems and processes are reviewed in depth and compared against industry best practice. (Figure 17)

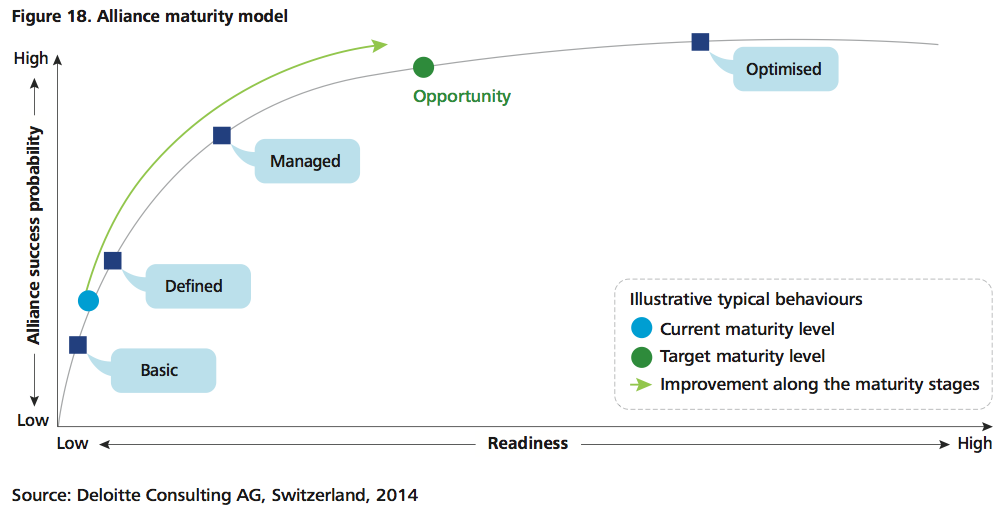

An Alliance Readiness Assessment evaluates a company’s maturity along four competencies. Deloitte’s experience has shown that companies with a higher level of maturity in their alliance capabilities are able to outperform competitors in terms of overall alliance success by a significant margin. It thus all starts from a clear view of existing gaps and a precisely defined desired future state. Figure 18 shows the four key maturity stages against which each company can map its alliance capabilities.

Deloitte’s Alliance Readiness Assessment enables alliance practitioners to ascertain their existing alliance capabilities and determine the prioritisation and sequencing of potential improvement initiatives. Identifying the current state against the background of industry characteristics and maturity is also the foundation of a desired target state definition. Deloitte’s diagnostics experience and industry expertise help to define the appropriate, company- and industry-specific target state and to formulate specific action steps towards optimisation of the company’s alliance management activities.

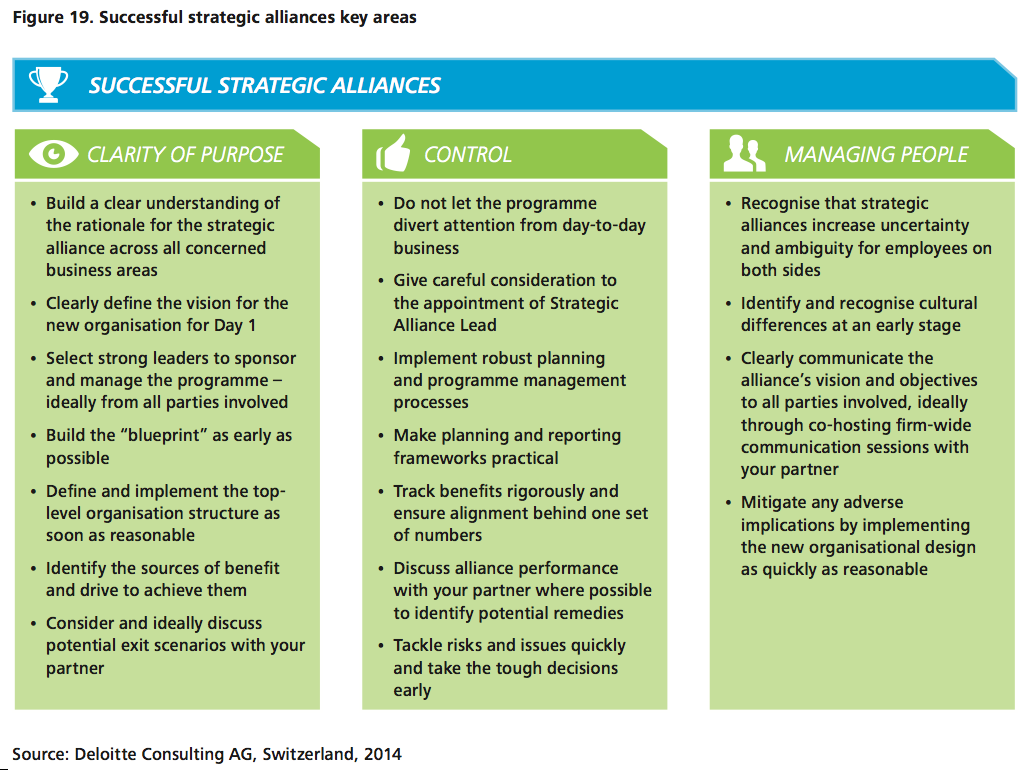

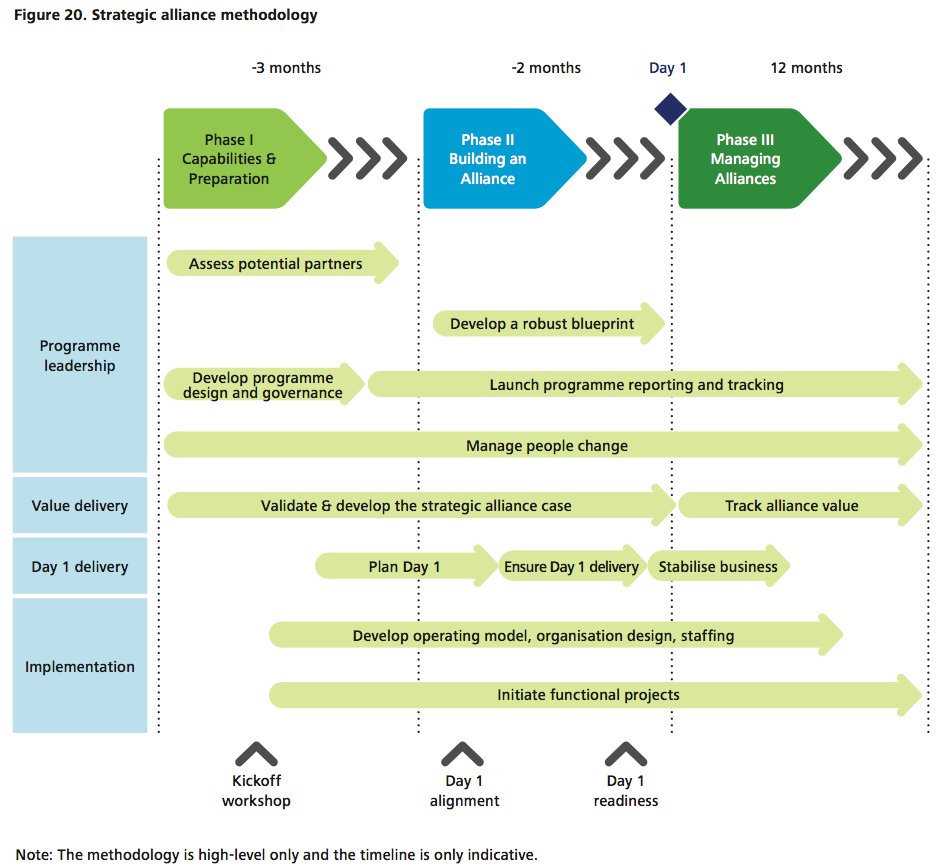

Strategic alliance methodology

Deloitte’s approach to establishing successful strategic alliances focuses on three key areas – clarity of purpose, control and managing people. Such a conceptual approach can and should always take account of specific corporate and organisational environments, drawing from a vast pool of industry and sub-industry leading experts, Deloitte works with clients to tailor the final approach to the client’s own needs. The systematic development of key enablers is however only the starting point; each of the three areas requires thorough dedication from senior leadership to ensure the long-term success of any strategic alliance (Figure 19).

To provide end-to-end guidance to clients through the entire process of forming, developing and delivering a strategic alliance, Deloitte typically adopts a three-phased implementation roadmap covering nine essential work streams, each of which focusses on the strategic and financial success of the strategic alliance at hand. Each phase is tailored to the specific needs of each client and their potential alliance partner, through intense, interactive workshop sessions in the project launching phase (Figure 20).