By KPMG

Introduction

In recent years, Japanese multinational companies have been acquiring an increasing number of foreign companies or divisions of companies. Although the acquisition of existing foreign companies or business divisions has been an effective means for Japanese multinational companies to quickly expand their business into foreign and new markets, it has created difficulties related to integrating the management of the acquired foreign companies or business divisions. From a purely managerial perspective, Japanese multinational companies may encounter a variety of difficulties due to the differences in the acquiring companies’ business policies and corporate cultures. In addition, integrating accounting and tax systems post acquisition may present certain challenges and may require improvements to such systems regardless of the new business structure. Furthermore, from an operations perspective, the new responsibility of properly managing the transfer prices applied to new intercompany transactions presents additional complexities. This may be quite challenging as many countries around the world, including Japan, have implemented their own set of transfer pricing regulations. Typically, properly managing transfer prices requires analyzing the intercompany transactions based on the functions performed, assets employed, and risks borne by each of the relevant entities. In recent years, one of the key areas of focus related to transfer pricing and international tax has been the treatment of intangible property. This article focuses on the management of intangible property (also referred as “intangibles”) in the context of transfer pricing and mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

Definition of Intangible Property for Tax Purpose

The definition of intangible property varies depending on the context and purpose, and the value of intangibles is often difficult to determine. Generally, intangible property as defined for tax purposes is not necessarily identical to the definition in accounting books. From a tax perspective, intangible property is typically considered a significant source for generating corporate profit. Thus, such intangible property has become one of the most important factors in determining the allocation of international taxable income.

Indeed, conceptualizing, defining, and valuing intangibles is one of the focal points of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project that the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Group of 20 (G20) have been developing. The Final Reports of the BEPS project were issued in 2015 and provide a broad definition of intangibles for transfer pricing purposes. Specifically, intangibles are defined as property “which is not a physical or financial asset, which is capable of being owned or controlled for use in commercial activities, and whose use or transfer would be compensated had it occurred in a transaction between independent parties in comparable circumstances.” The broad and general definition reflects the difficulty of defining the intangibles and the fact that the BEPS discussion involves many countries that have possibly conflicting interests among them. Moreover, since unique intangibles may be created, depending on the industry and the business environment, it is hard to present a specific, all-encompassing, concrete definition of intangibles. Given the differing tax laws, rules, and interpretations with respect to the definition of intangible property across countries, there is no clear unified position that applies to each case, and consequently, international conflicts between the tax authorities representing different jurisdictions have arisen frequently.

IP Issues

Historically, international tax and transfer pricing practitioners have allocated profits across multinational companies and their respective jurisdictions based on primarily economic ownership, while keeping an eye on the economic implications of legal ownership. A common transfer pricing approach was to first allocate profit based on routine return to entities that performed relatively routine activities and then allocate the residual profit to the entity(ies) owning intangibles and funding their creation. Therefore, to the extent important intangibles are owned and funded by the entity in a low-tax jurisdiction, a significant level of profit is attributable to the entity in the low-tax jurisdiction. As a result, the global tax burden of the multinational company is decreased and the overall global effective tax rate of the multinational company is reduced. However, one of the important points clearly articulated in the BEPS Final Reports is that a company should not expect residual profit allocation to be attributable based on merely funding development activities or holding the legal ownership of intangibles. This will be one of the most significant changes that BEPS will have on transfer pricing and international tax. Japanese multinational companies have generally been less aggressive with respect to tax planning to achieve significantly lower tax burdens. Differences in tax laws, corporate cultures, respective tax authorities value, and other factors contributed to the more conservative tax planning strategies used by Japanese multinational companies. Nevertheless, all transfer pricing and tax planning strategies related to intangible property will be impacted by the BEPS project.

Besides the concept and definition of intangibles, the BEPS project also tackles the related issues of information disclosure and disclosure requirements for tax avoidance schemes. Specifically, the new transfer pricing documentation regulations that incorporate elements of the BEPS Final Reports require much greater disclosure of information and significantly increased analysis and support of transfer pricing policies. Under such regulations, the parent company must account for its group operations and understand the value chain of the businesses, and perform detailed analyses and documentation on the economic substance at the entity in which the intangible property resides. Therefore, one of the major problems that is expected to arise is the conflict of interests not only between the tax authorities of countries on opposite sides of the intercompany transactions, but also between those tax authorities and any other tax authority involved in the transaction flow. For example, the tax authority of a country with enabling assets or resources (e.g., technology and know-how, natural resources, brands, markets, etc.) may emphasize the economic or high-value importance of those assets or resources in an effort to justify attribution of a higher level of tax revenue from these assets or resources.

However, the tax authority of the countries relevant to the company’s intercompany transactions will also likely have access to the same information disclosed by the company in its transfer pricing documentation (such as master file and country-by-country report) and may have their own (potentially contradictory) perspective. Therefore, it is particularly important for Japanese multinational companies to consider carefully how their transfer pricing arrangements are described and supported in their transfer pricing documentation, taking into account the perspectives of the relevant tax authorities and traits of each country involved in the intercompany transactions. To some extent, these issues have existed historically. Still, given the increased focus and demands surrounding BEPS, Japanese multinational companies must consider actions required in the future, especially when a company residing in a relatively low tax jurisdiction participates in an intercompany transaction related to intangibles or is planning to have such a transaction, or when the ownership of intangibles is unintentionally diversified as a result of acquisitions.

In summary, although the BEPS Final Reports do not define intangibles in a clear manner, the new rules relating to transfer pricing documentation require greater disclosure of information and transparency and obligate a company to provide a clear explanation of its intangibles and their respective transfer pricing arrangements. Given the greater visibility provided to the relevant tax authorities regarding the company’s intercompany transactions and the potentially conflicting perspective the tax authorities may have, especially for the intangibles related matters, the companies should be careful with respect to the treatment of intangibles and how they are discussed in the new transfer pricing documentation.

Intangible Transaction and Economic Substance

The OECD and the BEPS Project have been debating issues related to intangibles and the economic substance of entities holding intangibles, as this directly links to strategies resulting in excessive tax savings/tax avoidance. Moreover, economic substance is also the key issue in several current transfer pricing dispute cases. With the release of the BEPS Final Reports and the resulting increased debate surrounding intangibles in the world, Japanese multinational companies may receive more scrutiny from the local tax authorities if the economic substance of entities holding ownership of intangibles do not align with profit allocations among the group companies.

Several key factors to consider when determining which entity(ies) should receive the return attributable to intangibles is which entities, in addition to funding IP, perform the functions related to development, enhancement, maintenance, protection, and exploitation of the intangibles. The BEPS position is that only entities performing these functions, in addition to funding IP development, should be attributed the intangible return. Despite the effort of the OECD and the BEPS Final Report, there is still no clear definition of intangible property. In addition, local tax authorities also implement BEPS Project by harmonizing it with their existing regulations, resulting in slightly different definitions and treatments across different jurisdictions. Therefore, the facts and the degree of documentation required to satisfy the tax authorities’ inquiries may vary by company, by industry, and by country. For example, in the case of the IT industry, the location of chief systems engineers, who make important decisions with respect to systems development and who lead projects, may be considered an important fact. Other important facts may include locally hired systems engineers and the Japanese parent company’s capability to manage contract development projects. It is worth noting that in addition to R&D activities, other business activities may create intangibles. Such activities may include brand strategy/management, marketing-enhancing brand awareness, and negotiation for business alliance or key contracts with customers. The company would be required to maintain solid analyses, facts, and documentation/evidence supporting the intangible property owner’s direct involvement in their development and management to establish the economic substance of the entity.

In the context of M&A, one strategy that may be utilized to reduce risk related to economic substance challenges by tax authorities is the cost-sharing arrangement (CSA). In a CSA, for example, the acquiring company and the acquired company become co-owners of the intangible property. In such an arrangement, both companies share the costs required to develop and generate the intangibles and will typically also be responsible for other key responsibilities such as manufacturing and/or distribution/sales and marketing in each company’s territories. However, a drawback of implementing a CSA would be less flexibility with respect to the company’s business strategy in light of the CSA requirements. A feasibility study would be important in the post-M&A integration phase to determine the viability of implementing the CSA option.

M&A and IP Migration

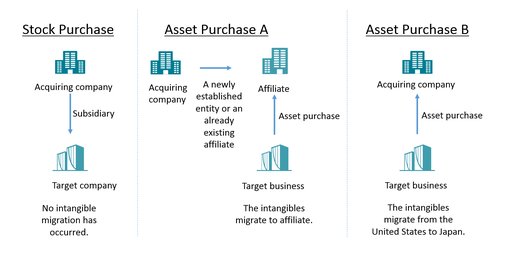

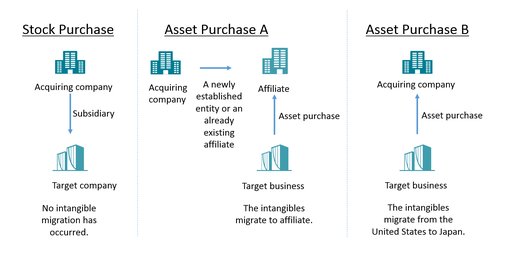

In the context of M&A, generally there are the two types of approaches to acquiring a company: (1) stock purchase, where the company acquires all or a portion of the target company’s shares and (2) asset purchase, where the company acquires the business assets related to the target company.

- Stock Purchase

In the case of a stock purchase transaction, the acquiring company (either a U.S. affiliate of the Japanese parent company or the Japanese parent company itself) acquires the business by purchasing the target company’s stocks from other shareholders. As an example, a Japanese acquiring company would be the parent company, and the target company being acquired by this company would become its subsidiary in the United States. Since the target U.S. company survives and continues holding the business assets, including any intangibles, the intangibles continue to reside in the United States and no intangible migration has occurred from the United States to Japan.

- Asset Purchase

In the case of an asset purchase transaction, the targeted U.S. company can be acquired by either a U.S. affiliate of the Japanese parent company or the Japanese parent company itself. When a U.S. affiliate (either a newly established entity or an already existing affiliate) purchases the business assets of the targeted U.S. company, the intangibles continue to reside in the United States since both companies are U.S. entities (i.e., the transfer of intangibles occurs within the United States). However, if the Japanese company directly purchases the business assets and subsequently contributes business assets (excluding intangible assets) intended for its local operations into the U.S. entity, then the Japanese company may become an owner of the intangibles of the acquired U.S. company. In such a case, the intangibles would migrate from the U.S. to Japan upon the execution of the M&A transaction.

Japanese multinational companies should consider carefully the ownership and location of intangibles of the acquired company during the planning and integration phase of the M&A as this becomes very important from the perspective of managing the transfer pricing. As mentioned previously, under the current transfer pricing regime, the economic ownership of the intangibles is generally entitled to receive the residual profits generated from these business operations. Moreover, the location of the intangibles owned by the acquired company (e.g., Japan, the United States. or other country) directly impacts the intercompany transaction flow and the profit allocation among the group companies, and thus, the location of intangibles is one of the key decisions in the planning and post-M&A integration phase. Nevertheless, as discussed above, with the BEPS Project, there is an increased focus and debate regarding intangible property, in particular with respect to the economic substance surrounding such transactions and the arm’s-length valuation of intangibles. The BEPS Project also discusses the applicability of specific valuation techniques to determine intangible value. Still, it would be difficult to calculate an intangible value that would be acceptable to multiple tax authorities since all the valuation techniques require several assumptions, some of which are not certain and are subjective in nature. While the general application of the purchase price allocation (PPA) is not generally accepted as a transfer pricing method, and the BEPS Project does contemplate using this valuation method, the PPA may sometimes be considered as a potential starting point for estimating intangible value. However, as there are several differences between financial accounting and transfer pricing treatments, certain adjustments may be necessary. In addition, certain adjustments related to timing may be necessary if a certain period of time has passed between the PPA and the transfer of the intangibles. Nevertheless, we have seen that some Japanese multinational companies leverage the results of PPA to help support the valuation of the intangible property when the company redesigns its intangible holding structure during the post-M&A integration phase.

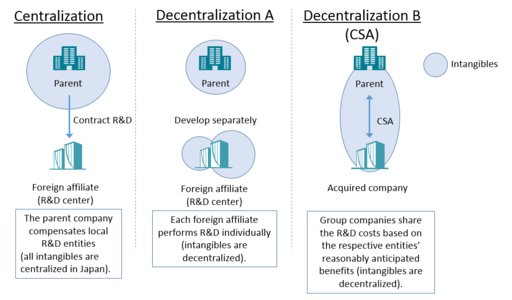

Managing IP

There are several approaches Japanese multinational companies may take to manage intangibles in the cross-border M&A. The simplest way is to migrate the acquired company’s intangibles and centralize all intangibles in the Japanese parent (centralization). Under this approach, the Japanese parent company typically compensates local research and development (R&D) entities under a contract R&D arrangement after the merger to keep the intangibles in Japan. Centralization is frequently used by Japanese multinational companies, because this approach does not create much complexity in their intercompany transactions and it is easier to manage transfer pricing issues. However, the intangibles centralization approach requires not only valuation and migration of intangibles to the Japanese parent, but also that the Japanese parent manage and monitor all R&D projects performed by local R&D entities and that it protect intangibles from infringements, which imposes some administrative burdens on the Japanese parent company. Furthermore, the Japanese parent will be responsible for funding all R&D investments and taking all the R&D risks. In some cases, the Japanese parent may continuously suffer losses due to the hefty R&D investment funding made to overseas R&D entities, which may unnecessarily increase the group’s overall global effective tax rate by putting the Japanese company in a loss position while making acquired companies profitable in jurisdictions outside Japan.

Some Japanese multinational companies adopt alternative approaches to centralization by developing intangibles that are owned in different jurisdictions (decentralization A). Typically, the motivation to use this approach is primarily derived from the company’s business strategy, which often relies on transferring R&D functions and risks to local foreign entities or increasing transparency to enhance performance evaluation of foreign entities. This approach is feasible, but the Japanese parent company must carefully manage its global intangible holding structure especially if the intangibles located in multiple jurisdictions begin creating collaboration benefits to the worldwide operations, or if several R&D entities participate in codevelopment projects. This issue may become significant if the Japanese parent company does not develop a global intangible holding structure after the company acquires a company, especially if the purpose of acquisition was to obtain a specific technology, brand, or intangibles owned by the target company.

Another decentralized approach involves implementing a CSA (decentralization B). Under the CSA, the affiliates in the various jurisdictions share the costs and risks associated with intangible development that may facilitate the Japanese parent company’s business objectives. It is expected that the number of Japanese companies using the CSA will increase in the future. However, one drawback to a CSA may be that the Japanese parent company may be scrutinized more closely by the tax authority, especially if the CSA is with an entity in a low-tax jurisdiction. Therefore, a feasibility study should be conducted in advance to avoid any adverse tax consequences of implementing the decentralization B approach.

In addition to the methods discussed in the preceding, there are many other approaches to manage intangibles, and the optimal structure will depend on the company’s specific business goals and circumstances. We suggest that Japanese parent companies review their global intangible holding structures to confirm the current structures actually fit the company’s business objectives. Specifically, after completing an acquisition, it would be worth reconsidering the global intangible holding structure, as this may affect the success of the post-M&A integration phase and operations efficiency. For example, some Japanese companies may acquire relatively smaller value intangibles from start-up companies in the same business area and centralize the acquired intangible properties in Japan based on a reasonable valuation analysis. This permits the Japanese parent company to efficiently manage all intangibles in Japan, which establishes a platform for the company’s global intangible holding structure. On the other hand, this may decrease the transparency with respect to performance evaluation of the acquired company, especially when the comparable profits method (CPM) is applied as a transfer pricing policy since such a policy guarantees a specific return to the entity. In some cases, the intangible decentralization approach better fits the company’s business objectives, particularly in a case in which the Japanese company acquires a relatively large enterprise owning substantial intangibles and the acquired company needs to continue its R&D investment independently. The M&A transaction can be the triggering event for the company to start reconsidering the current intangible holding structure.

Cost-Sharing Arrangement

CSAs are commonly used by multinational companies to allocate intangible development costs, for tax strategy purposes, and for various business strategy reasons, such as managing cash globally to bear significant developing costs, allocating risks associated with the development activities, and conducting R&D activities closer to the market and customers, etc.

When multinational companies develop and manage the economic ownership of the intangibles generated under the cost-sharing rules in the respective countries, the entities participating in the CSA will be able to allocate the costs of developing the intangibles based on the respective entities’ reasonably anticipated benefits. In this way, if the CSA meets the specified requirements in the respective countries, the CSA participants will not have to license the use of intangibles developed under the CSA from each other. Instead, the non-routine profit or loss generated based on the intangibles will be allocated in accordance with the economic ownership of the intangibles and as determined by the reasonable anticipated benefits of each CSA participant. It should be noted that economic ownership is not necessarily the same as legal ownership. CSAs are common for U.S. multinational companies, as the rules and requirements for CSAs are clearer and well established in the U.S. Treasury Regulation 482-7. On the other hand, Japanese rules for CSAs in the Commissioner’s Directive on the Establishment of Instructions for the Administration of Transfer Pricing Matters (Japanese Transfer Pricing Administrative Guidelines) 2-14 to 2-18 are not as clear as the U.S. cost-sharing rules in Treasury Regulation 482-7. For example, there is no clear guidance on the buy-in or buy-out payment necessary for the inception or termination of the CSA. It needs to be noted that Japanese cost-sharing rules and the tax authority’s views on cost sharing are not always the same as those of the United States, and thus, a CSA commonly used by U.S. multination companies may not always be the best option in cases involving Japan.

Post-M&A Intangible Property Management for Japanese Companies

Having said that, there are many Japanese companies successfully using CSAs to manage the cost of developing intangibles and to manage the economic ownership of the intangibles, both from a tax strategy and business strategy perspective, but there are also many Japanese companies successfully managing the intangibles without using CSAs by clearly distinguishing and separating the intangibles developed and owned by their respective entities. However, it is clear that there are many Japanese companies that are not strategically managing the intangibles at all. This is especially prevalent in cases of acquisitions of new companies that own significant intangibles. This increased difficulty of properly managing the group companies’ development activities and economic ownership of the intangibles results in these companies facing significant tax risk, especially when the intangibles generate significant profit or loss and where economic ownership of the intangibles is not clear.

It is not common for Japanese multinational companies to manage intangible property merely for tax saving purposes; instead, they focus on developing a tax strategy aligned with their business strategies. However, it is not rare for Japanese multinational companies to inherit an aggressive tax strategy associated with intangibles acquired through the acquisition of U.S. companies. In these occasions, some Japanese multinational companies plan ahead and reorganize the intangibles ownership during the acquisition based on their future business and tax strategies. Nevertheless, some Japanese multinational companies proceed with the acquisition without sufficient planning for the intangibles, which may significantly impact the future success from both business and tax strategy perspectives. As a leading practice, it is important for Japanese multinational companies to strategically determine the structure of the future intangible ownership from a tax strategy perspective and as part of the overall business strategy.

Japanese tax reform in 2016 is expected to require a master file and country-by-country report based on Action 13 of the BEPS project. Moreover, understanding the company’s value chain including how intangibles are developed and owned from the economic perspective and, most importantly, how intangibles are managed, will be very helpful to companies in preparing Action 13 documentation as BEPS Action 13 requires a description of the supply chain for certain segments of a company’s business with a chart or diagram depicting the supply chain being acceptable. An alternative approach that Japanese multinational companies may consider to manage transfer pricing risk related to intangibles is an advance pricing agreement (APA). Since M&A can have a significant impact to value chain management, it is important for the multinational company to consider the impact to the overall group’s value chain before the acquisition.

Conclusion

In general, U.S. multinational companies have internal resources to develop and manage the company’s tax strategy while using external resources for dealing with more complex tax strategies, especially those associated with cross-border M&A transactions. In contrast, many Japanese multinational companies consider tax as a cost of doing business and treat it more as a compliance matter rather than an opportunity for implementing strategies, and thus, Japanese multinational companies maintain and use limited resources in this area, even for complex cross-border M&A transactions and other more complex tax matters. However, there is an opportunity, and in fact a necessity, for developing tax strategy where appropriate, either prior to or in the early stages of an M&A transaction, as this may contribute to a more efficient and effective postmerger integration of the acquired entity. Managing the group’s intangibles from a tax strategy perspective will require putting appropriate internal agreements in place, determining the internal pricing policy including the transaction flow, and documenting the global transfer pricing. In addition, it will require a strategic approach from a business perspective, such as managing the global cash flow and allocating the risk for intangible development and other business reasons. However, these efforts foster proper management of intangibles, whi