Executive summary: a new era of M&A

A new era of M&A has emerged, which is changing the face of corporate Britain. Over the last three years the M&A market has leapt back to life. Three forces – private capital and in particular PE, investor activism and globalisation – have converged to reshape the fundamental dynamics of the M&A marketplace. First, PE has grown rapidly so that over the last few years it is frequently outmanoeuvring corporates in transactions.

Further, we believe that the influence of private capital over the transaction marketplace is likely to grow significantly over the next three years. Second, recent years have seen (institutional) investors taking a much more proactive interest in the ability of public companies to get the most value out of the portfolio of corporate assets they control. Finally, globalisation has come to the fore for many companies in recent history. Allied with fewer opportunities to grow from a domestic base, companies are increasingly looking to enter overseas markets, often through acquisitions. We have found that many UK public companies have M&A capabilities that are inadequate to compete successfully in tomorrow’s transactions marketplace.

Beaten to the punch?

Most elite, world-beating companies are built through savvy, well-executed, M&A strategies. Regardless of sector, getting to the top involves an astute management of a portfolio of businesses. However, pressure to optimise future parenting power of corporates’ business assets continues to build. Although strong in many areas, our research reveals a significant variation between average performance and upper quartile in terms of M&A organisational performance with listed corporates. This in turn is likely to translate into poor financial performance in transactions, meaning the senior management team is at risk. We found many UK-listed companies lack the required focus and have overly fragmented decision- making processes, which may well affect their ability to be successful in future M&A transactions. Further, well over half of UK-listed corporates agree the complex structure of such businesses is a major inhibitor of M&A success.

Clearly then there is a requirement within most UK-listed corporates to become more fleet of foot in M&A by building a focused transaction capability.

Pressure on all sides

The new M&A environment poses some stiff challenges for the management of listed corporates. Corporates are under pressure from all sides. First, our research shows that in open auctions for UK companies, PE was successful in 74 per cent of bids in 2005 compared with only 30 per cent in 2001. Second, during recent years more UK-listed corporates have conducted deals outside their normal geography or product area, especially overseas. We found between 2002 and 2005 there was a 78 per cent increase in deals outside corporates’ existing geographical market or sector.

Also, we polled the views of CFOs finding that they score PE capability significantly higher than corporates across most parts of an M&A transaction, including being more skilled in using the capital markets, in the tactics of bids/ auctions and in moving at the required speed. Further, our research shows that poorly executed M&A transactions are a leading cause of distress for underperforming businesses. In order to pursue a growth strategy led by M&A, it is imperative corporates enhance their ability to win deals. Our extensive, year-long research has distilled from the best of corporate and PE practice five key disciplines to provide a foundation for success.

Five disciplines for success

Making sure that a company develops a focused, faster moving, M&A capability for the long-term should be top of the boardroom agenda. In the face of increasing firepower from private capital, the top management needs to act with urgency around the following five disciplines:

- Clarity of purpose: Too few businesses see M&A as a core discipline. Further there is a lack of clarity around responsibilities for transactions. By contrast, best practice organisations exhibit clarity and rigour across all phases of every transaction.

- Parent power: Success requires corporates to beef-up their parenting prowess. Financial institutions are stepping up the pressure on listed firms to demonstrate they are the best owners of their portfolio of companies.

More importance should be placed on the discipline of exiting businesses at the right time and for the right price. - Know your prey: Given the pace at which M&A activity is conducted, corporates need to devote significant resources to identifying targets well ahead of them coming into play. This smart execution of appropriate deals will allow them to compete effectively for transactions.

- Incentives to execute: Nothing shows the difference in approach between the PE house and the corporate world more than the sequence of events that follows the completion of a deal. In the best run PE houses there is intense early action and a huge focus on setting the near- term objectives that will lead to a profitable exit.

- Integration: The ability to extract maximum value from a transaction is a must for corporates. Too few treat the integration as a separate part of the overall transaction. Best practice firms start planning for the integration in the pre-deal phase.

Companies should be able to explain why they are the ‘best parent’ of the business they run. Where they are not the best parent they should be developing plans to resolve the issue1. Hermes Investment Principles.

A new era of M&A?

A defining force of corporate success today is M&A.

Few, if any, of the world’s major companies have arrived at the apex of corporate success without a top-notch M&A capability and conducting a vast range of transactions.

GlaxoSmithKline, HSBC, RBS, Vodafone and WPP are among the biggest, most successful companies in the United Kingdom. Some of them have been around for a long time; some are relative newcomers. Without exception all have changed beyond recognition in the last two decades due to successful M&A strategies.

All these companies have built a world-class, M&A, organisational capability. M&A is a vital strategic lever for public companies. Many listed corporates in the United Kingdom have good, but arguably not world-class, transactional skills and capability. In the future, however, it will be essential to improve this capability vastly – to extract value and improve their ability to parent the businesses they run.

The M&A market has leapt back to life over the last three years. Deal volumes are up, so too is the value of deals. But today’s market has very different dynamics to those of the boom of the dot.com era. This new era of M&A is been shaped by a quicker pace and greater sophistication of buyers and sellers. Corporates need to raise their game, or they will lose out on key deals.

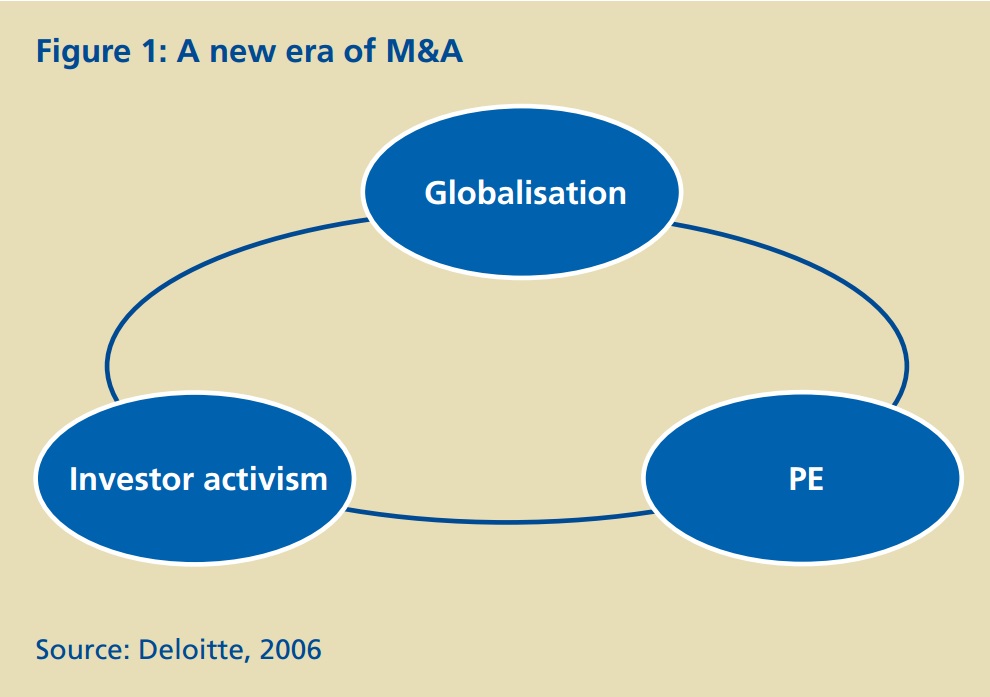

Three forces – PE, investor activism and globalisation – have converged to reshape the fundamental dynamics of the M&A marketplace (Figure 1).

Firstly, the relentless rise of PE, a defining force of the last five years, will accelerate over the coming years. PE houses will continue to sharpen their capability to make complex deals work. Certainly their capital backers seem convinced of this. The capital flowing into PE, much of it from traditional pension funds, has reached an astonishing scale. For example, in the United States around $750 billion has been invested by public pension funds over the last five years2. We believe that the influence of private capital over the transaction marketplace is likely to grow significantly over the next three years with up to €1 trillion at the disposal of PE in Europe3. Given the emergence of club deals, very few of Europe’s listed companies are now out of range for PE bidders.

Our research of UK transactions over the last five years shows the increasing success of PE. Between 2001 and 2005, PE won on average just over half of all auction deals. The change over this period has been dramatic from a success rate of 30 per cent in 2001 to 74 per cent in 20054. Further we polled CFOs of FTSE 350 companies about the impact PE funds have on driving deals in their industry. Nearly half the corporates polled assessed the impact as high or very high. Further, when asked the same question about the future, around three-quarters believe the impact will grow5.

Secondly, recent years have seen a rise in investor activism. Across financial markets there has been growing interest in the ability of listed companies to improve the parenting of the businesses they run. This section starts with a quote from the recently published ten investment principles issued by Hermes, the UK institutional investor, which is just one example. The bitter proxy contest at HJ Heinz in the United States is another excellent example. Activist investor Trian Fund wanted a bigger say in the strategic direction of Heinz. A bitter battle has ensued over control of the direction of corporate strategy.

It is now common practice for investors to criticise management openly for underperformance, suggest strategic changes and ask for a seat on the board6.

This can have positive impact on a company’s share price. A recent report found that companies where funds had been active displayed stock price increases averaging almost ten per cent in the month following a fund’s position being made public7.

Thirdly, globalisation has had a significant impact on deal making. All corners of business have been influenced by the rapid rise of emerging markets. In terms of global investment, one dollar in every four now involves China or India8. In the world of M&A we have seen emerging market multinationals playing a bigger role. This was led by the acquisition by Mittal (the world’s number one steel producer, from India) of Arcelor, and Lenovo’s (a Chinese computer maker) takeover of IBM’s PC division. Further the tenfold rise in the number of cross-border deals over the last 15 years allied with lower growth at home, means that UK corporates will need to be more involved in foreign transactions in the future9.

This shift in the fundamental forces governing M&A markets will continue to bring changes both in terms of market dynamics and, more importantly, UK corporates’ deal-making behaviour. Our analysis of over 1000 deals across the last five years shows UK corporates are changing the types of deals they do in response to the pressures of the new era of M&A.

Traditionally FTSE 350 companies have tended to undertake corporate transactions in the same geographical and product domains in which they already operate. We gained a deeper understanding of these changes from this established position by mapping deals over a matrix based on the principal market of the acquired entity and the business area. Figure 2 shows how UK public-listed firms are beginning to move away from their comfort zone.

The profile of transactions over five years shows an average of 69 per cent of deals in the same market geography and product area. This compares with 16 per cent in new product lines but in the same geography, in other words, the United Kingdom. However, within the former category, between 2003 and 2005 there has been a fall from 73 per cent to 65 per cent. Further, the mid-year data for 2006 shows a fall into the mid-50s.

Interesting insights in the shift underway can also be gained from analysis of size and market capitalisation of transactions. Figure 3 shows the largest average size of transaction takes place when firms buy in a similar product market but a new geography – these tend to be higher risk deals.

There is a dramatic polarisation between firms with a market capitalisation of greater than £10 billion and those below that threshold. In the former, where the average deal size is around £350 million, the average number of deals is around one per year. By contrast, acquiring firms below the £10 billion threshold have deal sizes nearly a third smaller, but on average are transacting five times more deals a year.

The dramatically shifting centres of gravity within M&A markets are having profound implications for corporates. We believe the focus needs to be on their organisational M&A capabilities to parent businesses and extract value from transactions. Pressure to use M&A as a vital lever in building corporate success will continue to build. Best practice shows how listed corporates can successfully change their business model through M&A.

For instance, the proportion of profits that HSBC derives from retail banking has grown from one per cent to 30 per cent over two decades, fuelled by purchases like Household in the United States and Midland Bank in the United Kingdom10. Undoubtedly, corporates are rising to the challenge of a new era of M&A. Are they changing quickly enough, however? Or are they likely to be caught flat-footed as this dramatic shift sweeps through M&A markets?

Flat-footed corporates? Meeting the best practice challenge

Recently, M&A markets have become faster moving and more competitive. PE houses and the best corporates are forging ahead in their ability to do deals. And, more importantly, they have built slicker M&A machines within their organisations. These best practice firms are setting the pace: too often conventionally structured, listed companies are left flat-footed at best and at worst, both management and company are extremely vulnerable.

These profound shifts demand organisational improvements and capabilities to compete. But given the changes in the M&A environment corporates need to adopt a new benchmark to measure their performance. At present, our assessment is that the gap is widening between the upper quartile and average public company based on the research and analysis performed for this report. Further, Deloitte researched 40 mergers in the United Kingdom. The study found that over half of businesses had a failed M&A transaction as the chief cause of their problem. In 40 per cent of cases the acquired business was subsequently sold11.

Where do corporates stand today? Most finance directors we polled thought their M&A capability was above average in all aspects of a transaction. For instance, asked whether they could respond quickly if a company came ‘into play’, CFOs rated their business on average above four out of five. Similar ratings were given to the capabilities around the rigour of aligning M&A and corporate strategies, their ability to execute a deal and finally the fact that they regularly review their portfolio of businesses12.

Nonetheless, a more critical assessment of corporates’ M&A capabilities is required. In spite of their favourable self- ratings, UK corporates need to be much more objective in assessing their real capabilities in the face of a rapidly evolving M&A marketplace. Corporates do acknowledge some areas for concern. Around 60 per cent agree that more complex structures in corporates can inhibit transactions13. Clearly the evidence cited earlier in this report – the growing likelihood of PE to win in auctions and the growing pressure from money managers.

Our own work does provide evidence of some improvement in the skills corporates deploy around transactions. Analysis of over 150 mergers spanning more than a decade shows a marked difference between those before and after 2002. For instance, UK companies exhibit three dimensions of becoming more prepared during the integration phase once a deal is complete. Firstly, companies are now three times more likely to have developed a plan for the integration of the acquired firm three months before the start of the merger.

Secondly, the appointment of a full-time manager with responsibility for managing the integration is twice as likely three months prior to the deal. Finally, listed firms are also now more likely to have developed a detailed communications plan ahead of a transaction14.

Any review of an M&A capability must start with an honest assessment of potential weaknesses. Our research shows the biggest area of focus is improving accountability and co-ordination across a transaction.

Fuzziness and fragmentation of responsibility across the transaction can increase the chances of dropping the baton. Figure 4 shows little consistency across the

FTSE 350 as to who owns the merger process at particular stages. The range of M&A-responsible positions within listed companies is significant at both the approval and execution phases. In most instances this is likely to reduce the effectiveness of the process.

It is true that corporates do need to have a more phased approach to integration due to their complexity. However, without a more holistic approach to mergers, corporates are unlikely to be able to compete in increasingly aggressive and sophisticated M&A markets.

Recognising this point many larger corporates have been hiring top M&A personnel from investment banks – Ford, Novartis and Aviva15, to name just a few. And so the gap between PE/upper quartile corporates and average public companies is growing wider.

Case study: Smiths Group

Frequent flyers are likely to be familiar with Smiths’ products without realising it. In every airport security check, the chances are that some of its technology is being used.

Smiths’ Group is a company that has transformed itself over the last five years. A core part of this development has been building an experienced and skilled M&A capability. CEO, Keith Butler-Wheelhouse, has pursued an explicit strategy of using transactions to power company growth and has done over 50 deals in the last half decade. With market capitalisation rising 50 per cent between 2003 and 2006, its professional M&A capability has played an important role in driving this growth. Four key components have set the Smiths’ team apart:

- Alignment of M&A strategy with corporate strategy. Although the business is made up of a number of divisions the M&A team works across the business preparing future transactions. For instance, it is common practice for the M&A team to work with the divisional heads of the business on several pre-approval business cases for board approval. This negates the need for frenetic board-meetings and approval processes in the heat of a deal.

- Core team with mandate across the business. Smiths’ has built a multi-disciplinary core M&A team. This involves a blend of experienced business heads with professional advisers from the worlds of accountancy and PE. This team works across the business with a mandate across the entire transaction from screen to integration.

- Continuous screening of potential deals. The M&A team acts as a catalyst across the business, continuously updating target screens, preliminary screens and pricings ranges. This ongoing dialogue enables the business to move rapidly into gear once a transaction launches.

- Continuity. Frequently, staying too long in the M&A team at a public company can inhibit career progression. More importantly the lack of a continuous process of screening targets means executives do not necessarily build up the expertise they could. Smiths’ has avoided many of these pitfalls and created a virtuous circle. The full-time process of screening and executing deals allows the team to build experience across transactions. High deal volumes attract professionals from both within and outside the business. This continuity has built a robust and unique M&A capability.

However, Smiths’ arguably still faces challenges, notably on two fronts. Firstly, some commentators argue that it could be more aggressive at extracting value. Secondly, some City activists who are opposed to conglomerates suggest Smiths’ has moved a little too far in this direction.

It is important to note, however, that not all best practice in M&A resides in major corporates and PE houses. Across the spectrum of listed firms there are examples of companies building capabilities that compete with the best. The case study on page 7 illustrates how Smiths’ Group has developed a successful M&A engine over the last five years. Such examples show how smaller public companies can overcome some of the inherent weaknesses of corporates, such as complexity, but focus on the synergies generated from integration opportunities.

Fit for the future?

New norms for corporate behaviour are being set by the best practice exhibited by PE houses and major corporates. The way these organisations value companies, execute acquisitions and subsequently deliver value through a well-orchestrated exit process is changing the face of corporate Britain. Clearly PE houses have different motivations for doing deals and operate under different constraints than public companies. Nevertheless there is nimbleness and a focus about the way acquisition is executed in PE that makes a positive difference to the chances of success in a competitive auction.The spectrum of practice in the way deals are conducted is broadening. As the pace and sophistication of deal- making forges ahead, too many listed companies risk falling behind – and this shift matters. Figure 5 illustrates the differences we have observed in the initial phase of deal-making capability between best practice and average organisations. Adoption of best practice has two main benefits. First, the speed and efficiency of the process can make the difference between winning a deal or not.

We estimate that it can take an average public company up to three times longer to prepare for a transaction. Second, the excessive friction during a deal in the organisation can lead to future problems. One executive remarked “our non-executives resent being repeatedly forced to the altar to do deals, due to lack of planning”16.

Companies need to be able to pursue a successful M&A strategy if they are to reach their full potential. They need to examine, understand and learn from best practice in M&A and incorporate the best and most relevant techniques in order to raise their game. But where should they begin?

By highlighting examples of good practice among PE houses and the best corporates, we have created a road map for corporates seeking to build a leaner, more professional and effective M&A machine. This pinpoints the five disciplines that can improve how corporates transact and implement deals.

Five disciplines of M&A best practice

1. Clarity of purpose

Few businesses see M&A as a core discipline. Further there is often a lack of clarity around responsibilities for transactions. By contrast, best practice firms exhibit great clarity and rigour across all phases of every transaction.We have found a huge variation in the set-up and operations of corporates’ M&A departments. Too often the M&A function is an uneasy compromise between several different executive groups. Part of this problem is a relative lack of experience. It is possible to find a great deal of skill and competence in corporates but they can still fall short against the best practice benchmark because they simply do not do enough deals, so there is neither the same collective memory, nor the same accumulation of experience.

Preparation and research is one area where PE houses, for example, demonstrate best practice. PE carries out heavy, but very focused, investment in due diligence very quickly – often three per cent of the projected cost of the deal according to Deloitte analysis. Partly this is required by a lower level of familiarity with the industry than that enjoyed by a trade buyer, and the need to secure debt funding. However, this research is also central to the decision-making process in PE, providing the information with which the investment committee of the PE house can challenge the deal sponsors and subject the acquisition case to rigorous testing.

Rigour is further ensured by the extensive use of third parties from outside the business to test and challenge investment assumptions. The entire process is designed to isolate precisely those factors that drive the cash generation, market dynamics and profit margin, and plot their volatility and variability through different phases in an economic cycle, because this can affect value.

Corporates tend to have a more complex and fragmented decision-making process. Given the number of participants within a corporate, there is a higher risk of slowing progress down, or making serious errors in the process. Best practice shows it is important that the handovers are made effectively across the organisation throughout the transaction.

Another example of where clarity of purpose plays its part is in cash and working capital management. Our research revealed much anecdotal evidence that suggested corporates frequently left value on the table through poor cash control. In PE, ‘cash is king’, as there is a focus on servicing the debt package that is part and parcel of most buyouts. Focusing on optimising the supply chain and managing cash collection carefully allows PE to create value. There are ancillary benefits too. Close monitoring of cash creates an improved level of discipline in compliance and will increase the likelihood of fraud being detected.

Finally, the set up of the M&A department is the source of many of the concealed problems leading to a lack of effectiveness. Clearly defined responsibilities between the centre and the divisions are vital in building the foundations of doing successful deals.

Action points:

- Interpret and agree the implications of the corporate strategy for M&A. This should be the basis for a clear set of objectives for the M&A team.

- Set up the M&A team with key metrics against this set of objectives, and have a mandate across the business, with well-established links to the board and strategy team.

- Clearly define roles and responsibilities in the deal execution process, including whose approval is required at each stage.

2. Parent power

Most companies buying a business expect to own it for ever. Disposal is not seen as a natural step towards the creation of value. However, City institutions are increasingly stepping up the pressure on listed companies to demonstrate they are the best owners of their portfolio of companies. Equal importance should be placed on exiting as acquisition.Best practice corporates we spoke to believe they do have a rigorous process to confirm that M&A strategy is aligned with corporate strategy. They regularly review their portfolios of business and, when they do decide to sell, they are good at executing the deal.

For instance, focus can generate returns. Our research reveals that proactive de-mergers create rather than destroy value. An analysis of 118 mergers over the last ten years shows that the majority of these deals created significant increases in shareholder value17.

There is a clear difference in attitude between best practice and most other companies. A best practice organisation sees the sale of a business as an opportunity to create value and looks forward to it as the successful completion of a period of ownership and investment.

On the other hand a company making a sale too often does so out of a sense of failure. The business has failed to live up to expectations, is no longer wanted and is therefore to be disposed of quickly, with the minimum of fuss.

There are exceptions, of course. For example, businesses that rigorously examine their portfolios on a systematic and regular basis and genuinely question whether they are the best owners for the subsidiary or whether it might be worth more to someone else. Being the right parent for an asset two years ago does not make it right now.

Changes in market and economic cycles can radically change the picture. The best businesses do this without sentiment and perhaps for that reason such groups know how to sell well and know too that selling does not have to be immediate. The decision in principle can be taken, but the execution delayed until pre-sale preparations are complete and the market conditions are right for value to be maximised.

Best practice:

- Continual reviewing of portfolios – testing whether there is still further value to be extracted or whether the business would be worth more to others

- Start ‘packaging’ the business for sale – maybe 18 months before the event itself

- Seek the right point in the business cycle to put the business on the market

- Run a highly efficient auction with properly prepared vendor due diligence

- Consider bringing in interim management to run the business up to the point of sale

3. Know your prey

It will no longer be enough for corporates to rely on superficial research on potential targets. Given the pace at which corporate activity is conducted, corporates need to devote significant resources into building an origination capability.

To meet the challenge from the smartest buyers with most effect, corporates need to be quick off the mark. They should have identified and be familiar with their potential targets well in advance of their coming available. This means knowing your prey.

When a target appears corporates should know from previous research whether or not it is one they want to pursue, how much it is worth to them and therefore whether they should bid. They should know too, when price may not be the dominant issue, and where they will be disadvantaged if an asset subsequently becomes owned by someone else.

In other words, corporates need to know their prey well and be fast to act. This is more likely to be achieved where there is a central point of authority that will help deliver the clarity and consistency needed. That authority has to be agreed throughout the organisation, so that what the board has decided is in harmony with what is required at a divisional level. It is however more than simply a matter of authority.

For most companies M&A is a secondary activity, because the prime function of any executive team is to manage what they have and deliver value from the assets already under ownership. Getting head office and the divisions into alignment is not easy. Nor is it easy to build an effective M&A origination and execution capability. Therefore, the challenge to all corporates is for the head office to have sufficient feel for divisional markets to know whether to support their M&A proposals or hold them back, to know whether to back them in acquisition-led or in organic growth. And such broad agreement is not the end of the matter.

Best practice shows the assessment of management is a key part of the process. The buyer needs to have confidence in whatever team is given authority. It requires both owner and management to understand clearly what the objectives of the business are, and how it is going to achieve them. Such clarity is harder to achieve in the corporate sphere.

Our research also reveals it is important to carry out friendly or hostile deals if possible. Our work reveals lukewarm transactions are three times more likely to destroy value, compared with those which are friendly or hostile18.

To match the pace at which best practice corporates and PE houses can get deals done, listed companies need to review their processes, to ensure there is clear ownership of the entire M&A proposition, from origination through to integration.

Action points:

- Use a well-researched dossier to provide the springboard for action once a target comes into play.

- Brief non-executive directors on potential targets prior to the deal to obtain pre-approval.

- Be flexible when consulting the board on these issues.

- Agree terms and conditions with advisers on a rolling basis.

4. Incentivise execution

Nothing shows the difference in approach between best practice and typical corporates more than the incentives to execute. Particularly in PE, management incentives can be brutally simple, focusing on achieving the required internal rate of return and value at exit. Corporate remuneration on the other hand has to serve a range of purposes with the impact being more diffused. There are, however, lessons that can be learned.

Finance directors in our poll recognised that PE tends to be better at delivering profit improvements after deals. They attribute this largely to the fact that PE management can be given large incentives to deliver.

This is certainly true. PE houses put in place management and employee incentives that tend to be single minded in their focus – getting their value through an internal rate of return or threshold price. Once the required returns have been delivered, PE houses are generally happy for incentives to deliver significant payments to management. The amount delivered, however large, is irrelevant, so long as management has delivered the required return. This provides management with a clear focus on what it is expected to deliver. On the other hand, incentives do not pay out if the targets have not been met.

These simple goals are not so readily available in the corporate sector, where incentives have to fit within the wider corporate structure. This means balancing the need to incentivise alongside other ongoing goals, such as retention, alignment with shareholders and market practice.

However, corporates can learn lessons from PE best practice about the style of incentives used and how pay can drive performance in the period following the deal: by identifying what success looks like, and by directing reward to those responsible for delivering this success. The key in this process is simplicity.

In terms of the definition of success, experience shows that there is often a mismatch between what is judged to be a success and what is actually measured. Incentives provide an opportunity to identify what the key drivers of success are and ensure that these are clearly communicated to management. This may involve moving away from senior management participation in the primary, long-term, incentive arrangement of the corporate, where performance is based on measures such as total shareholder return or earnings per share.

It may be that incentives should instead be focused on the performance of the acquired business alone. Incentives should also concentrate on the period that is relevant for delivering value in the business following the deal, which may not follow the typical, three-year rolling pattern of corporate incentive plans. In order to reinforce this message, corporates should ensure that where performance is not delivered, management does not get rewarded.

Corporates should also ensure that incentives are focused on those who are actually involved in the deal, with the power to make it work. This is not only a question of incentives. It can be more difficult to generate value from a merger because of the different interest groups within a business, giving the possibility of multiple objectives, which may or may not have been prioritised. Successful acquirers identify those who are responsible for delivering against clear and measurable targets and empower them to do so. Targeted incentives can be used to reinforce this message, for example by asking management to put some ‘skin in the game’, by investing some of their own money, in return for participation in the new plan.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, corporates should worry less about market practice and more about what is right for the business. Corporates need to accept that there may not be a one-size-fits-all model for pay and incentives, and that bespoke arrangements for the acquired company may be the best way to drive the performance of business.

Action points:

- Identify clear measurable targets across the transaction.

- Keep it simple. Overly complex incentive packages within a corporate regime and hierarchy can be a recipe for problems.

- Clearly define who is accountable for delivering the deal and structure incentives accordingly.

5. Integration

The ability to extract the maximum value from a transaction in the shortest timeframe is a must for corporates. Too few treat the integration as a separate part of the overall transaction. Best practice firms start planning for the integration in the pre-deal phase.

Mergers can easily become high-risk growth strategies with little guarantee of success. Indeed all too often companies pop the champagne corks on completion of a deal and fail to pay enough attention to the integration. Experience shows that in this situation, the merger will ultimately hit the rocks, not because the company has chosen the wrong business, although some do, but due to poor integration of the acquisition. Experience also shows that at the point when the ink dries on a contract, it is often possible to tell if the merger will succeed. Further, the demands of the new M&A era mean that public-listed companies need to adopt and understand the valueextraction habit.

Failure to integrate separate corporate cultures saps staff morale and proves to be a distraction to senior management. Getting the merger of two organisations off to a good start and capturing the momentum of the deal is critical to extracting the maximum potential value. Planning the integration before the completion of the deal is imperative to ensure that the companies do not fall into the trap of relaxing and thinking the hard work is over; the opposite is nearly always true and the toughest decisions are still to be made.

Best practice shows that change must be driven through quickly. Typically, an integration has a 90-day, post-deal window in which to succeed or fail, but it is usually determined by the quality of the planning, which can start well before the day the deal closes. As a guide most merger activity should be planned and costed over the 90-day period prior to the first operational day of the merged business. Clearly the integration will not be complete at this stage. However, the merger blueprint or strategy, financial goals, operational delivery plans and communication plans should have been developed and agreed so that the maximum benefit can be derived straight from ‘the off’.

Further, upper quartile performers consistently demonstrate a combination of four factors at play to make the integration successful:

- Clarity of purpose – required prior to the completion of the deal. Building a clear understanding of the rationale and vision for the merger; selecting strong leaders to sponsor, manage and lead the programme; implementing the top-level organisation structure and identifying and prioritising the sources of benefit is critical to creating and maintaining momentum throughout the integration.

- Control – ensuring that the integration programme does not divert attention from managing day-to-day operations is paramount for success. Implementing robust planning, programme management, benefit tracking and reporting methodologies, which are both pragmatic and adequately resourced will give management confidence in and visibility of the programme. This coupled with the ability to tackle risks and issues quickly and take the tough decisions early helps to ensure that the programme is both structured and controlled.

- Managing people – businesses that recognise that mergers increase uncertainty and ambiguity for employees on both sides are halfway to removing these issues caused by implementation. Best practice businesses prepare their HR team early on and ensure it is skilled and fully resourced; they identify and recognise cultural differences and plan for change at all levels.

- Communications – also key across the deal, with upper quartile companies being better prepared to communicate the key parts of the integration than average corporates. This phase tests if the necessary processes are in place to ensure effective engagement of internal and external stakeholders.

Action points:

- Ensure planning starts well in advance of the deal; companies that are well prepared tend to deliver greater shareholder value.

- Appoint an integration director to work as part of the M&A team at least three months prior to the completion of the deal.

- Handle the softer ‘people and communication issues’ with equal ranking to hard edged financial issues.

Conclusion: Fighting back in M&A

Fundamental changes are taking place in the nature of M&A activity in the United Kingdom – making the whole process faster and more focused. Most corporates will need a successful M&A strategy to deliver the growth their shareholders expect but our research shows in many instances they are increasingly slow off the mark. As a result, there is a clear need for many UK-listed companies to build an M&A machine that can build the confidence of institutional investors and extract greater value from deals.

This is very much an organisational, rather than a financial issue. In this report we have identified five best practice disciplines that should be adopted by listed corporates to add a cutting edge to their M&A capability. In the face of the dramatic changes in the M&A market, corporates need to incorporate these disciplines into a new M&A machine to become agile, athletic and win in M&A.

In essence, corporate centres provide three main services to companies: compliance and governance, operation of shared services and value-adding activities. The creation of a high performance M&A machine should sit within the latter of these categories. There are several aspects to establishing a cutting edge function, but three fundamentals are worth mentioning:

- M&A core operation: The M&A team must have a wellarticulated, value-adding proposition. Efficiency at both buying and selling companies is central to this proposition. An established team, of at least three to five years’ standing, is likely to have a positive impact on the quality and approach to deals.

- Must be wired to the corporate strategy: Any M&A team must be constantly linked to the corporate strategy and be able to translate the implications for the M&A strategy. Typically this would focus on the targeting of key markets or revenue streams, growth areas and geographic expansion.

- M&A team structure: A key to success lies in the building of a multidisciplinary team, which has a combination of professional adviser experience and business expertise. Typically a corporate should look to have a core team of two or three M&A practitioners. Working out how to inject M&A best practice from PE houses or investment banks should be high on the corporate agenda. In addition, the core team should be supplemented by two or three high flying executives who rotate into the team every couple of years.

Corporates intent on building their business prowess and a successful future must enhance their M&A capabilities. The question they must pose is: are they really fit for the fight ahead?

All but a few of Britain’s elite corporates have gained their place at the top through M&A. There are some extremely useful lessons to be learnt from the behaviour of the best corporates and PE players. The five disciplines we have outlined attempt to capture the most important issues for corporates. As a matter of urgency we believe boards should review their M&A infrastructure and processes, to build a cutting edge M&A machine as a key ingredient of future corporate success.

Methodology

This report is based on an extensive research programme. To investigate fully the issue of improving corporates’ M&A capabilities we have undertaken the following four work-streams:

- Analysis of 1065 transactions between 2001 and 2006 involving UK-listed companies worth more than £113 billion in 11 different sectors, to understand how the dynamics of deals are changing

- Case studies based on face-to-face interviews with over 20 Heads of M&A at leading FTSE 350 corporates on the application of PE best practice

- Commissioned Ipsos-Mori to interview independently 65 FTSE 350 CFOs or Finance Directors on the M&A capabilities of UK-listed corporates

- Appraisal of 64 deals over the last several years on the preparedness of corporates to extract value from transactions through integration.

This year-long research project attempts to synthesise each of these separate strands into a coherent set of insights and actions to enable corporates to improve their M&A transactional capability.

Footnotes

- The Hermes Principles, Hermes Fund Management, London.

- Financial Times, How US public funds fuel private equity, 28 August 2006.

- Based on €300 billion equity, €300 billion debt and €300-€400 billion matched funding by 2009.

- www.mergermarket.com

- Deloitte & Touche LLP/IpsosMori: CFO M&A Survey of UK FTSE100 & 250Corporates, 2006.

- Financial Times, Active investors can go where others fear to tread, 23 August 2006.

- Citigroup report, 2005.

- UNCTAD World Investment Report, 2005.

- ibid.

- Speech by Michael Geoghegan – CEO, HSBC: Deloitte GFSI Summit, Athens, May 2006.

- Financial Times, Why mergers are not for amateurs, 12 February 2006.

- IpsosMori/Deloitte Survey, 2006.

- IpsosMori/Deloitte Survey, 2006.

- Deloitte, Doing better, getting harder – merger’s state of health, 2006.

- Financial News, Companies Shun M&A Advisers, 4 September 2006.

- Executive Interview, May 2006.

- Deloitte research, 2005.

- Deloitte and Cass Business School, 2005.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.