By Charles Lee – the Economist Intelligence Unit

Contributors: Laurel West, Xu Sitao, Wu Chen, Lina Xu, Abe De Ramos, Elizabeth Fry, Madelaine Drohan, Matt Eiden, Christopher Wilson, Gavin Jaunky, David Simonds (cover image), Gaddi Tam (design)

Executive summary

Among the many signs of China’s increasing economic power has been a surge in the number of Chinese companies seeking to buy assets overseas. In 2009, while developed economies remained mired in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, Chinese companies made a record number of crossborder acquisitions—some 298 in total. Much of China’s investment has been welcomed by cash-strapped Western companies that would be hard-pressed to survive without it. But China’s buying spree has raised a number of concerns, particularly where it has involved state-owned enterprises (SOEs). And like their Western counterparts before them, Chinese companies are discovering just how difficult it can be to get mergers and acquisitions (M&A) right, especially when they are crossborder deals.

A brave new world: The climate for Chinese M&A abroad, is our attempt to understand the concerns and aspirations of Chinese companies planning to buy overseas assets and to provide these companies with a view of the issues and concerns of potential targets and foreign regulators.

Among the key findings of our research:

• The financial crisis has created opportunities galore. The global financial crisis has triggered a sea change in foreign attitudes towards Chinese investors, particularly in the US, Canada and Europe. Indeed, in the face of the worst global business environment in decades, Chinese entities still managed to generate a record 298 crossborder M&A deals in 2009, according to data from Thomson Reuters. While these investments have ostensibly been welcomed, Chinese acquisitions will still need to be carefully planned and managed in order to ensure success in sealing the deal. Moreover, investment in a few sectors, such as natural resources and certain types of technology, will remain sensitive.

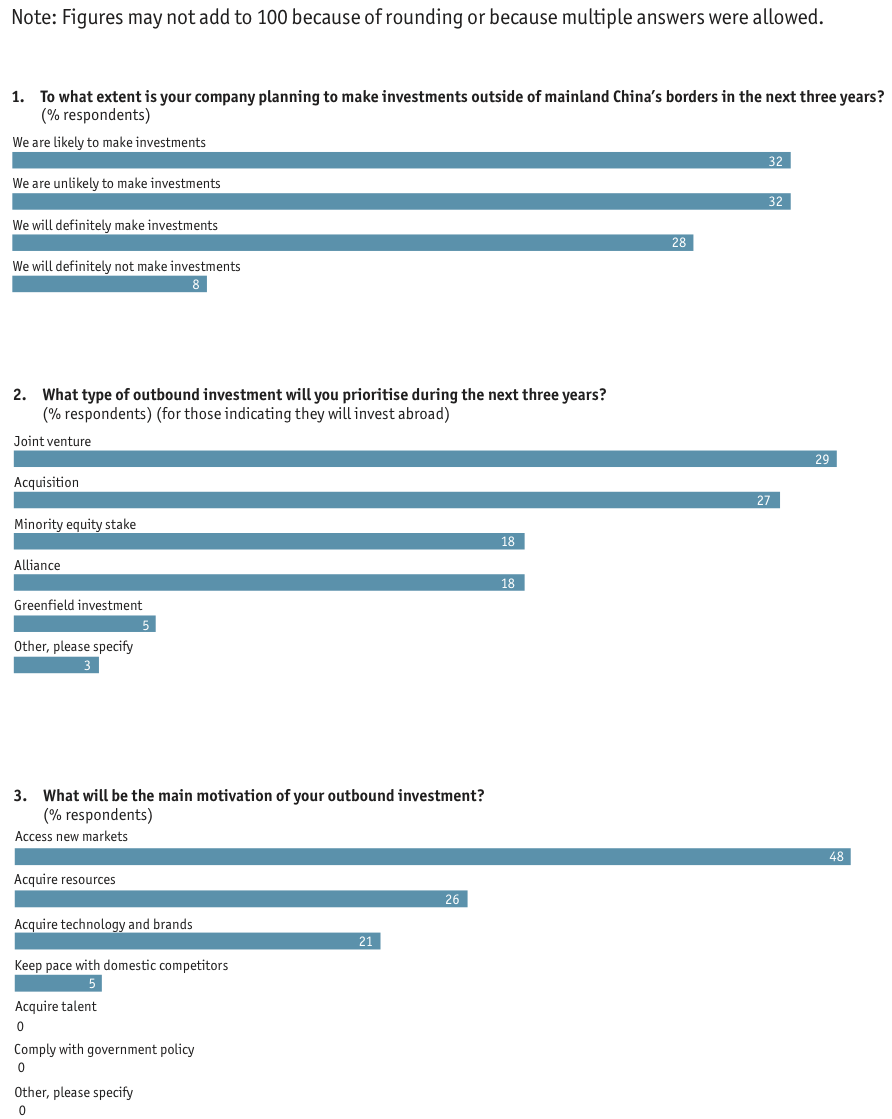

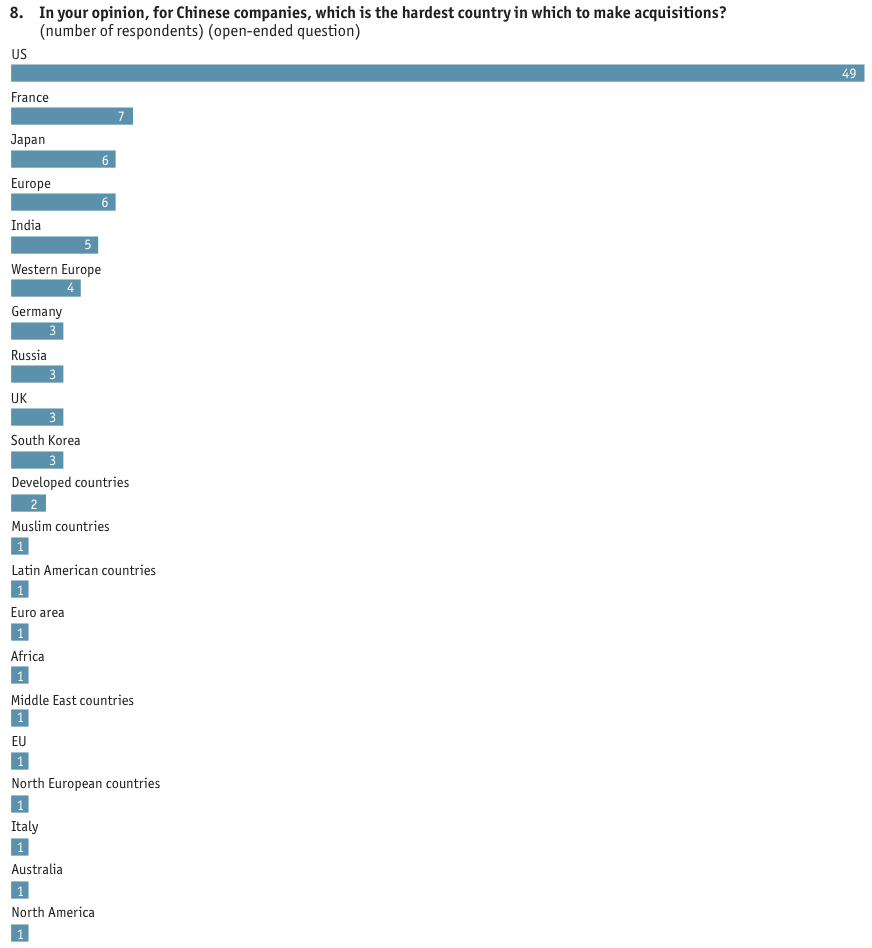

• Chinese acquirers feel unprepared for crossborder acquisitions… In our survey of 110 Chinese executives, 82% of respondents identified lack of management expertise in handling outbound investment as the biggest challenge for Chinese companies. Only 39% feel they know what is required to integrate a foreign acquisition. Only 39% of survey respondents said they had identified specific companies that would be attractive to them within their chosen geographic markets—increasing the risk that Chinese buyers could succumb to the temptation to buy assets that have become available as a result of the global financial crisis, rather than focusing on carefully researched targets.

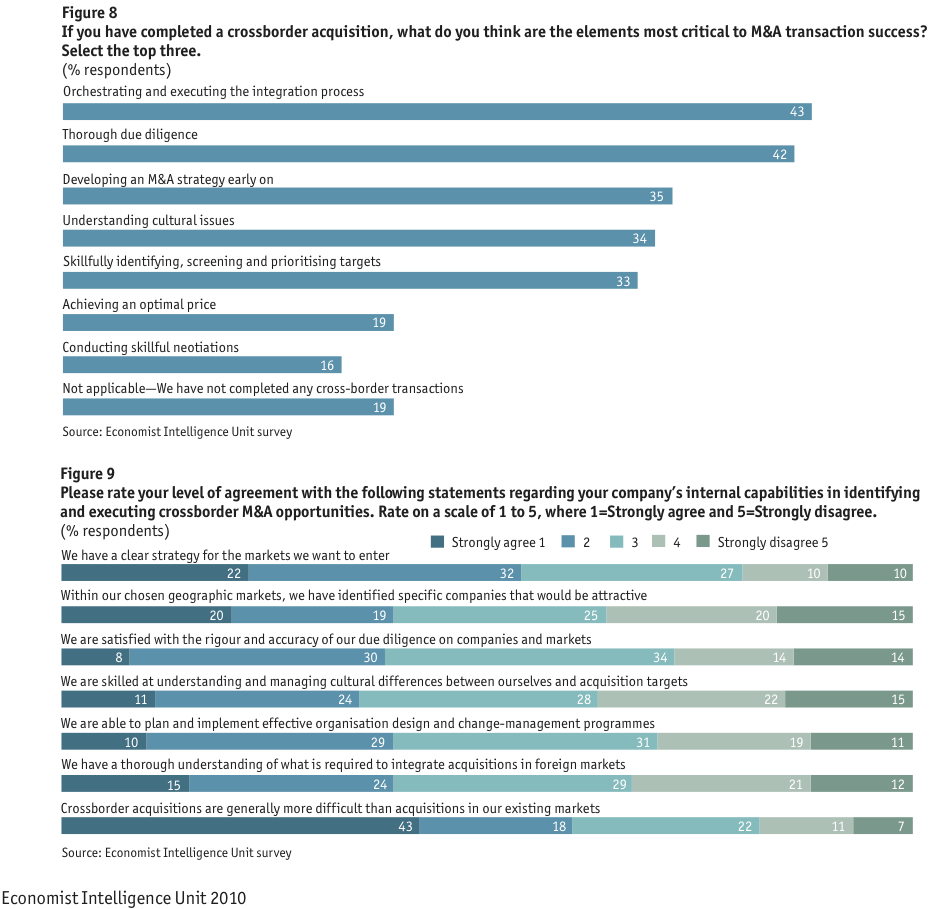

• …as a result, they are lowering their ambitions. In the past Chinese acquirers have shown a tendency to seek outright ownership or at least managerial control of their targets. Our analysis of deals worth more than US$50m between 2004 and 2009 showed that half the deals involved 50-100% ownership of the targets and a further 13% involved substantial (minority) stakes of 25-50%. But there are many signs of a realisation that this may not be the best approach for a number of reasons, not least because it can set off alarm bells among the foreign public and regulators. Among survey respondents who said they were definitely or likely to make an overseas investment, 47% would prefer to strike either joint ventures (29%) or alliances (18%) while only 27% said they would do so through acquisitions.

• Outbound M&A remains dominated by SOEs. According to our analysis of deals worth more than US$50m between 2004 and 2009, an overwhelming majority of China’s outbound M&A transactions— 81%—have been made by state-owned entities. This will remain a cause for concern abroad, not only because many deals involve control of natural resources but also because state ownership seems to confer unfair advantages on the acquired companies.

• As economic conditions recover and competition for deals heats up, Chinese purchasers could be at a disadvantage. Foreign counterparts to deals and M&A advisers say that with the worst of the financial crisis over the competition for M&A targets is also recovering. The need for Chinese companies to gain approval from their government for investment—and the time required and uncertainty created—is likely to put them at a disadvantage versus the competition. Would-be buyers could also find potential acquisition targets less willing to sell as the recovery of financial markets provides them with other ways to raise funds.

• Lack of communication is a major obstacle. Most of the Chinese companies interviewed were well aware of the tensions created by some high-profile deals and were concerned about the environment this had created. Advisers and counterparties from Washington to Canberra pointed to a need for Chinese investors to take a less narrow, procedural approach to investment and look at the bigger picture—to present the commercial and economic rationale for their acquisitions and a clear plan of what they will do with them—and also to explain who they are and what role, if any, the Chinese government plays in their decision-making. They should be prepared to explain these things to all stakeholders—politicians, media, communities, employees—even if a deal does not face regulatory scrutiny.

• Demands for reciprocity will increase. Despite years of foreign investment in China and the country’s accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), many foreign multinationals complain that access to the China market is far from unfettered. China has its own complaints about Western protectionism, particularly in the trade arena. But as many industries in Western countries continue to struggle with sluggish economic growth or recession, they will be asking their governments why they should allow Chinese companies access to their markets if their openness is not reciprocated.

• Western fears about job losses and intellectual-property protection remain acute. China now is seeking technology, and it views overseas M&A as one means by which to acquire this. But how can it buy technology without buying manufacturing capacity, which leads to concerns that the manufacturing capacity will be shut down and shipped back to China? This fear is particularly acute in Europe. In the US, too, the perception that China lacks respect for intellectual property hurts its companies when seeking to strike tech-oriented deals.

• Despite the hurdles, Chinese investment abroad will increase. Most of the parties interviewed for this report expect Chinese investment abroad to increase. While resources will remain a major target for investment, other sectors that are also expected to see increased activity include agribusiness, bio- science, clean energy and real estate.

These are still early days for China’s overseas investment. In coming years not only will the volume of crossborder deals involving Chinese parties grow, but so will the diversity of Chinese players, their targets and strategies. It is a natural process of Chinese companies integrating ever more closely into the global marketplace. And even as Chinese companies will have to continue adapting to the intricacies and vagaries of crossborder M&A transactions, their increasing ubiquity will also permanently alter the global game of corporate deal-making.

Introduction

As the second decade of the 21st century opens, China’s spectacular rise shows no signs of abating—if anything, it seems to be speeding up. While advanced countries of the West are still staggering from the aftermath of the global financial crisis, China’s GDP surged by 8.7% in 2009 and continues to grow strongly, bringing the country’s economy close to Japan’s as the world’s second largest. This has already prompted some to talk exuberantly about a new geopolitical era dominated by a Group of Two (G2), comprising China and the US. Against this backdrop, it is not surprising that the business world is struggling to come to terms with the impact of China’s growing strength—on a national economic level and industry by industry.

China’s economic reforms, which the late Deng Xiaoping launched in 1978, were founded on openness to commerce with the rest of the world and, indeed, its export sectors have served as a wondrous engine of growth in the past three decades. Equally important, however, have been the huge inflows of foreign investment that provided the capital required to fuel the growth of China’s industrial machine. China rolled out the red carpet to foreign direct investors, who were given enthusiastic policy sanction to tap the country’s fabled market (and labour force) of more than one billion people. Businesses worldwide responded in kind, pouring tens of billions of dollars into a whole spectrum of Chinese industries—with those producing export goods receiving the lion’s share.

Now, the game has changed. China is no longer dependent on foreign capital. On the contrary, armed with more than US$2trn in foreign-currency reserves, it is on a worldwide investment mission, and perhaps the most high-profile aspect of this emerging trend has been its search for overseas assets to buy. The effects of the global financial crisis are both pulling and pushing more and more Chinese executives to take their businesses abroad. The global financial crisis could very well prove to be the point at which many Chinese companies emerge as true equals of established multinational companies (MNCs). The rest of the world is starting to recognise it, too. This realisation, combined with the perception that Chinese companies have very deep pockets, has prompted many foreigners to look at Chinese investment in a more favourable light. Witness how quickly bankrupt General Motors (GM) decided to unload its Hummer division to Sichuan Tengzhong Heavy Industrial Machinery (although Beijing has refused to approve the deal), and how Ford Motor moved to sell Volvo, one of its key brands, to Geely (a deal which seems likely to be approved).

The crisis has not only thrown up some great bargains in the distressed economies of the West, but it has also made Chinese policymakers realise that parking the bulk of their foreign reserves in the bonds of over-indebted Western governments will not generate the highest returns for the hard-working Chinese people. What is more, China still needs huge amounts of foreign-sourced raw materials, technologies and managerial knowhow if it is to build a truly world-class economy. All of this seems to indicate that China’s outbound investment, including M&A, will explode in coming years.

But Chinese companies today are venturing into a highly uncertain overseas environment, particularly those that are seeking to acquire foreign companies. Whereas Chinese executives see their growing international profile as a natural evolution mirroring the increasing globalisation of China’s economy, many foreigners are wary about Chinese intentions and ambition—even if they would welcome an infusion of Chinese money.

Rumblings

The highest-profile manifestation to date of this concern was the torrent of publicity given to the failed bid by Aluminum Corporation of China (Chinalco) to increase its stake in Rio Tinto, an Anglo-Australian mining giant, in 2009 (in 2008 Chinalco, together with Alcoa of the US, had bought a 12% stake in Rio Tinto). Foreigners’ suspicions of China’s intentions were further aroused when Chinese officials subsequently arrested the head of Rio Tinto’s China office, Stern Hu, on charges of industrial espionage and bribery. Mr Hu is a mainland-born Chinese but has Australian citizenship.

There are rumblings on many different levels. Much of the scrutiny has focused on natural resources, the sector where large Chinese companies have been most acquisitive and where many countries are sensitive to foreign investment, regardless of the source. However, there is plenty of evidence of an emerging wave of Chinese investment aimed at securing technology and other intellectual capital—for everything from car manufacturing to green technologies—as well as the management expertise to transform mainland companies into truly world-class players (though these deals are only beginning to show up in the data for acquisitions worth more than US$50m). This is raising concerns that go beyond the security of natural-resources supply and touch on more fundamental economic concerns. Of specific worry is the potential for manufacturing and jobs to be relocated to China. There is also a growing resentment among foreign companies that feel they are not being granted equal access to Chinese assets and markets, and hints that this could fan—or indeed, perhaps already is fanning—the flames of protectionism. Of course, China has its own views on the matter, with officials frequently commenting that other countries’ criticisms are unjustified and stem from frustrations about problems in their own economies.

How can Chinese companies best navigate the volatile cross-currents they face abroad? How do foreign companies and regulators really feel about doing deals with Chinese firms, especially now that many of them are no longer in a position of strength? How serious is the protectionist threat against Chinese investment? Are there any Chinese companies and executives whose past experiences could provide useful guidance for others?

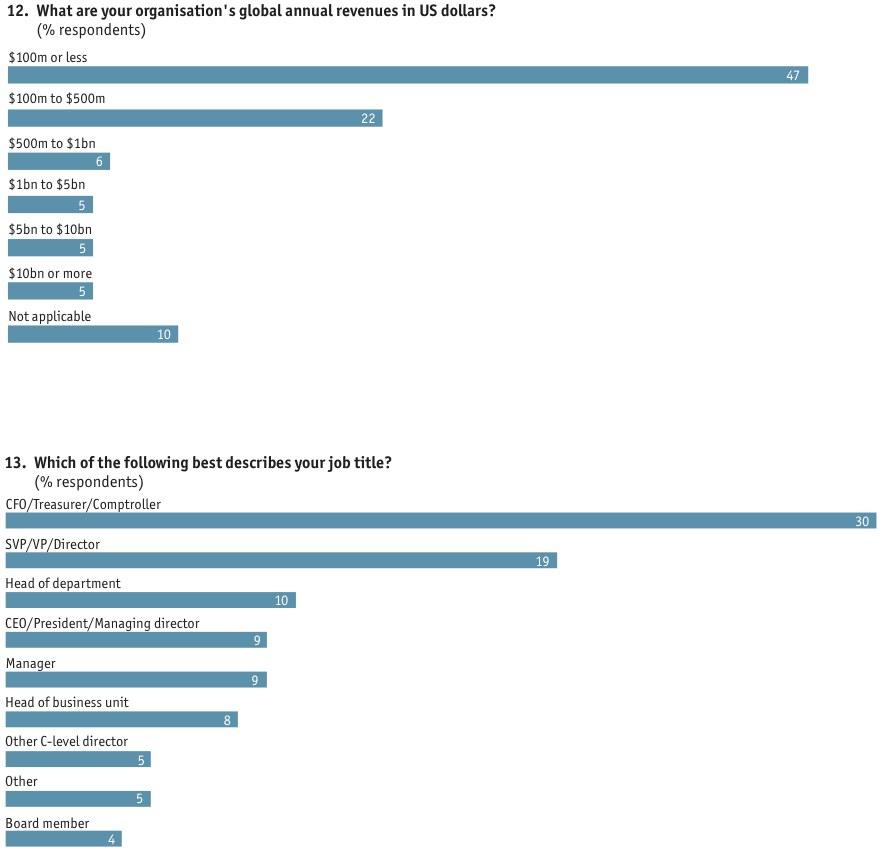

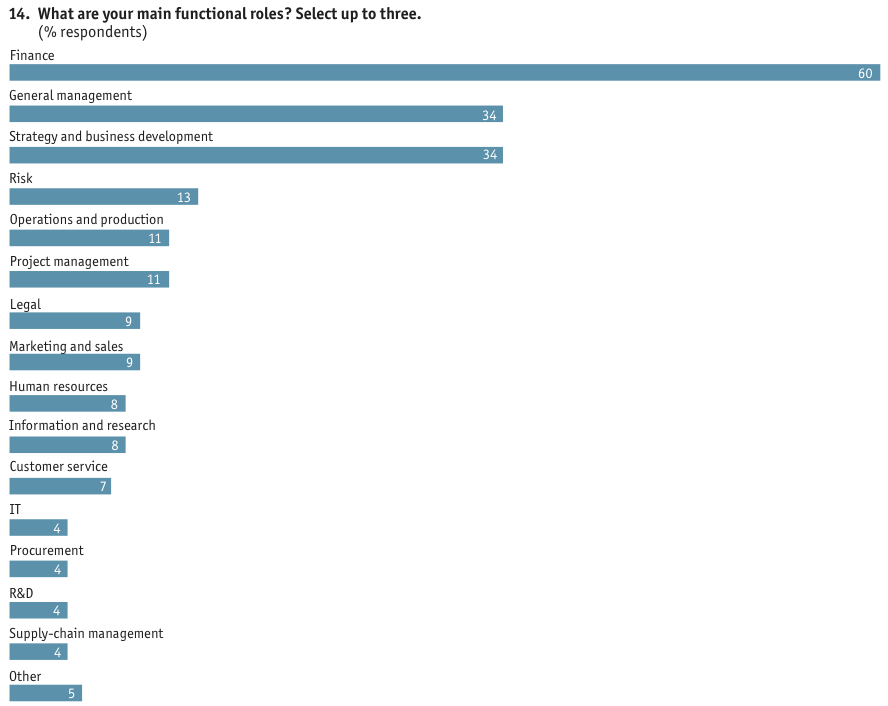

To assess the opportunities and risks abroad for China’s emerging MNCs and to identify the key elements of successful transactions, we have taken a multi-pronged approach. To understand the Chinese view of the difficulties of crossborder M&A, we have conducted in-depth interviews with 15 large Chinese companies with experience—both successful and failed—of investing abroad, as well as 40 interviews with foreign counterparties to deals and investment advisers. We have analysed available data on Chinese companies’ crossborder transactions in the past five years (focusing on deals worth more than US$50m) and conducted an online survey of 110 Chinese executives about their future overseas ambitions. Given that most Chinese companies are still at the stage of learning how to make deals successfully (indeed, many of our interviewees said that actually identifying targets was a major challenge), we have focused largely on the deal-making process, although post-merger integration is clearly of enormous concern to acquirers.

Our findings indicate that for Chinese companies the window of opportunity for overseas deals has opened markedly. But how long it will stay that way or how much wider it can open is unknown. These are still early days for China’s overseas investment in general. As the rest of the world’s economies recover, potential acquisition targets will surely drive a harder bargain. Chinese companies will have to contend with rival bids from other resurgent MNCs for deals. They may also have to deal with rising protectionism, fuelled by fears of China’s rapidly growing power.

Chapter 1: China takes on (not over) the world

The Chinese are latecomers to foreign investment. But they seem both ubiquitous and more conspicuous than others, at least judging by recent headlines. Data reveal that the surge in overseas investment is rather more modest

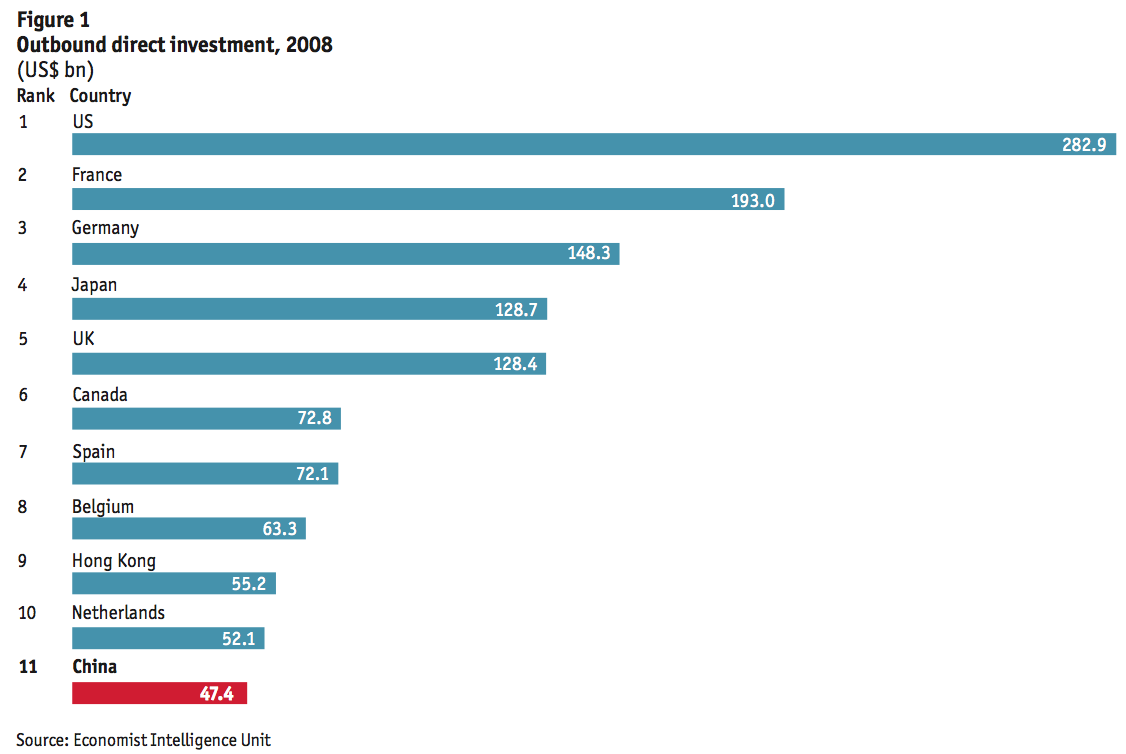

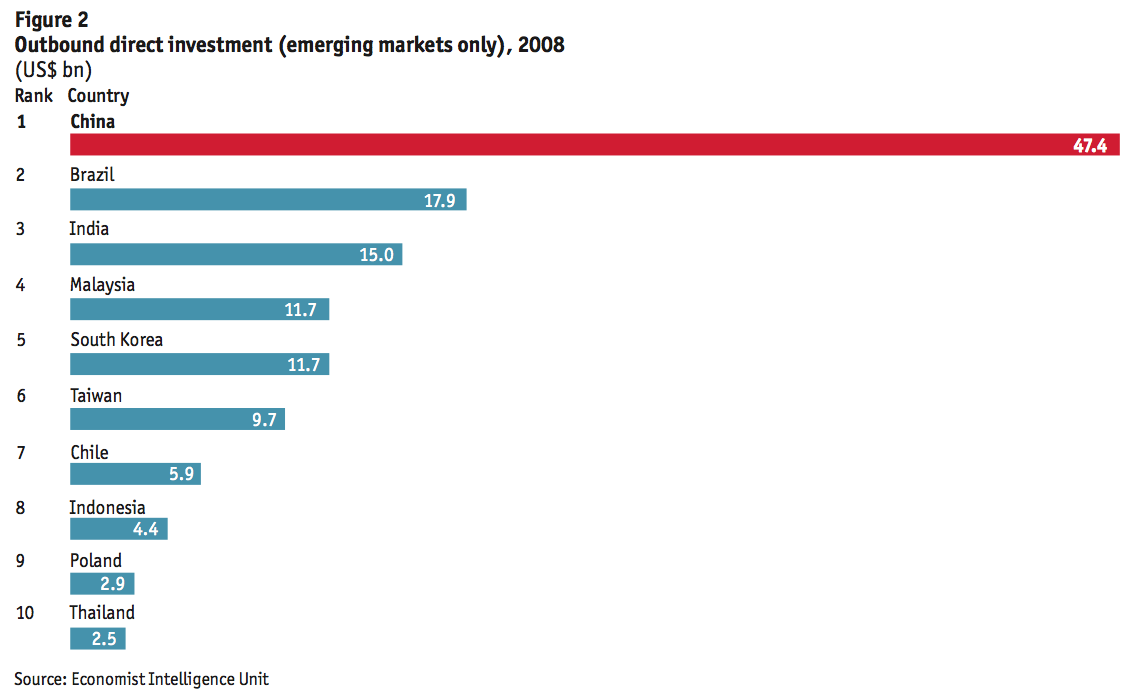

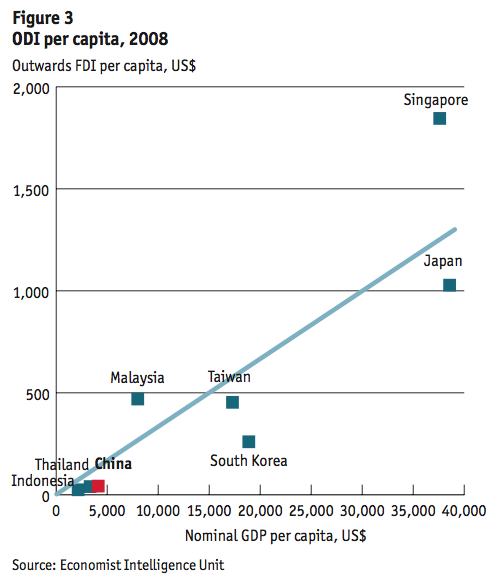

Before the onset of the global financial crisis, China’s annual overseas direct investment (ODI) flows (including M&A and greenfield investment) trailed far behind those of rich Western countries. China was not a top 20 ODI-generating country until 2005 and even in its breakout year of 2008 only managed to climb to 11th place (see Figure 1). That year, the US, France, Germany, Japan and the UK all pumped out far more ODI than China. China did out-invest its emerging markets competitors in 2008 in absolute terms (see Figure 2), but relative to the wealth of its people (measured in terms of ODI and GDP per capita), China is no more adventuresome than Indonesia or Thailand (see Figure 3). In other words, when China’s sheer population size is taken into account, its ODI patterns have hardly been astonishing.

China’s vision for its companies to become international players was spelled out only in 1999 with the introduction of the “go global” policy. The government subsequently identified ODI as one of the keystones of its Tenth Five-Year Plan (2001-06) and the current 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-10), both of which aimed to bring the corporate sector in line with the economy’s growing globalisation. Still, outbound M&A remained insignificant until 2005, when it passed the US$10bn mark for the first time. After that, the pace rapidly picked up, with the total for outbound M&A deals estimated at US$73bn in 2008, according to data from Thomson Reuters, which include all outbound deals where the ultimate acquirer is a Chinese company. Thomson Reuters data shows that M&A activity fell to US$42.6bn in 2009, but 2008 figures were inflated by China Unicom’s acquisition of China Netcom’s Hong Kong-based operations.

Despite the drop in value, the outbreak of the global financial crisis has not slowed down the volume of outbound deals—in 2009 there were a record number of transactions, some 298 in total.

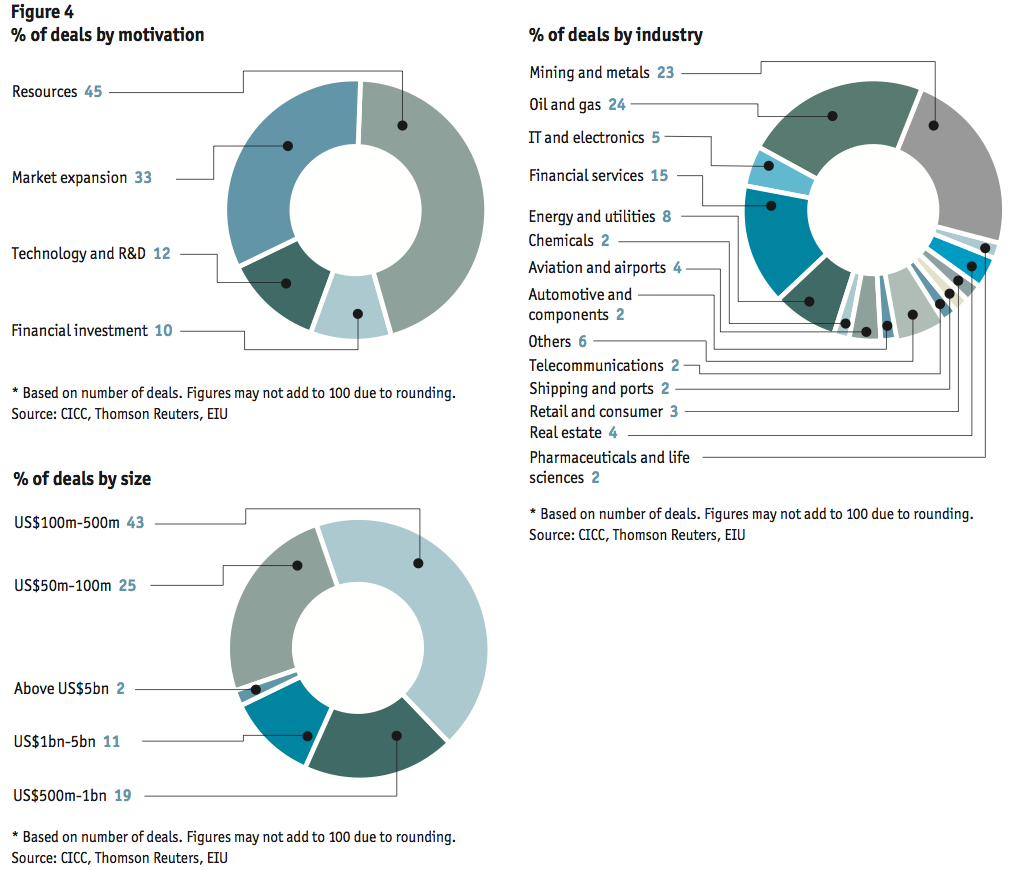

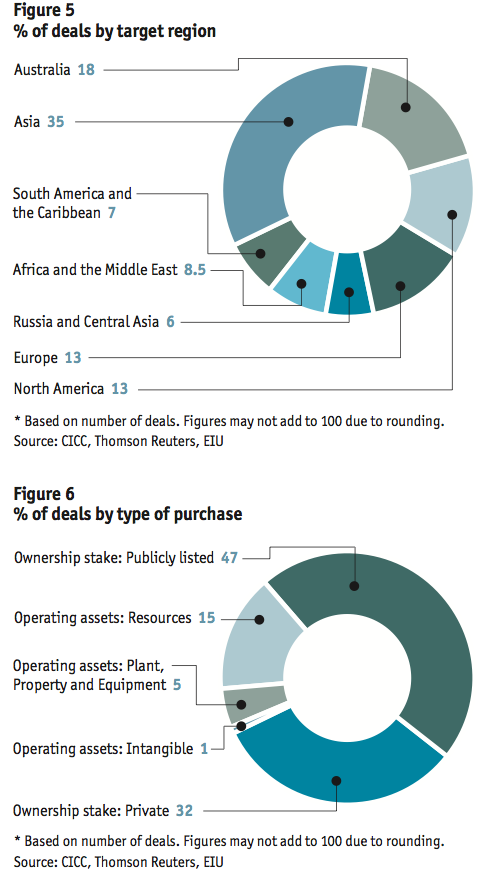

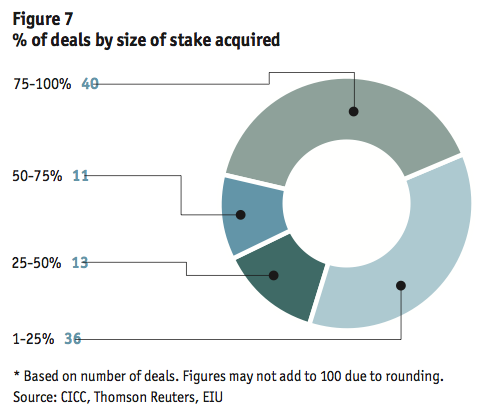

What about the main characteristics of Chinese M&A deals so far? Our analysis of 172 completed deals worth more than US$50m undertaken by Chinese companies between 2004 and November 2009 (see Figures 4-7) found that:

• Almost half of China’s outbound M&A transactions have been driven by the need to support the country’s growing demand for energy and natural resources, followed by the desire to access new markets and technology, and potential capital gains.

• China targeted more acquisitions in its backyard—Asia, focused on deals in Hong Kong’s financial services industry—than in any other region. In terms of non-Asian countries, Australia was the favourite destination, with 35 deals or 18% of the total (including withdrawn deals), followed by the US, with 16 deals or 8%. In terms of value, however, Australia attracted the most amount of Chinese money at US$28bn, or one-fifth of the total, and the deals (including failed bids) were overwhelmingly concentrated in the metals and mining sector (69%). Of the top-ten destinations representing 81% of the total deal value, seven were developed countries, with Kazakhstan, South Africa and Russia accounting for the other 14%.

• Most of China’s outbound acquisitions were made after 2006—72% for resource-driven acquisitions, and 73% for market-seeking, financial/strategic and technology acquisitions combined. Between 2004 and 2006 the oil and gas sector attracted the most Chinese interest, while between 2007 and 2009 interest shifted to the metals and mining sector. Of financial/strategic acquisitions, only two were made before 2007. In the technology-related areas of IT & electronics, and pharmaceutical & life sciences, the US attracted the most number of deals.

• An overwhelming majority of China’s outbound M&A transactions—81%—have been made by state-owned entities. Private enterprises have been noticeably slow to latch onto China’s “go global” policy, accounting for only 12% of transactions (the remainder were made by statutory bodies).

• Four in five Chinese outbound M&A deals involved equity stakes in corporate entities, with operations and workforce requiring integration with the acquirer’s own operations.

• To date Chinese outbound investors have shown a desire to buy a controlling influence (though this appears to be changing), with half the number of deals involving 50-100% ownership of the targets and a further 13% involving substantial (minority) stakes of 25-50%.

• Of the 22 failed deals, all but one were in developed countries (Yemen was the sole exception but involved a US-owned company there).

• Of the 68 transactions with valuation data available, 52 acquirers paid a premium to the targets’ last-traded share price, trailing share-price average or book value.

State drivers of investment

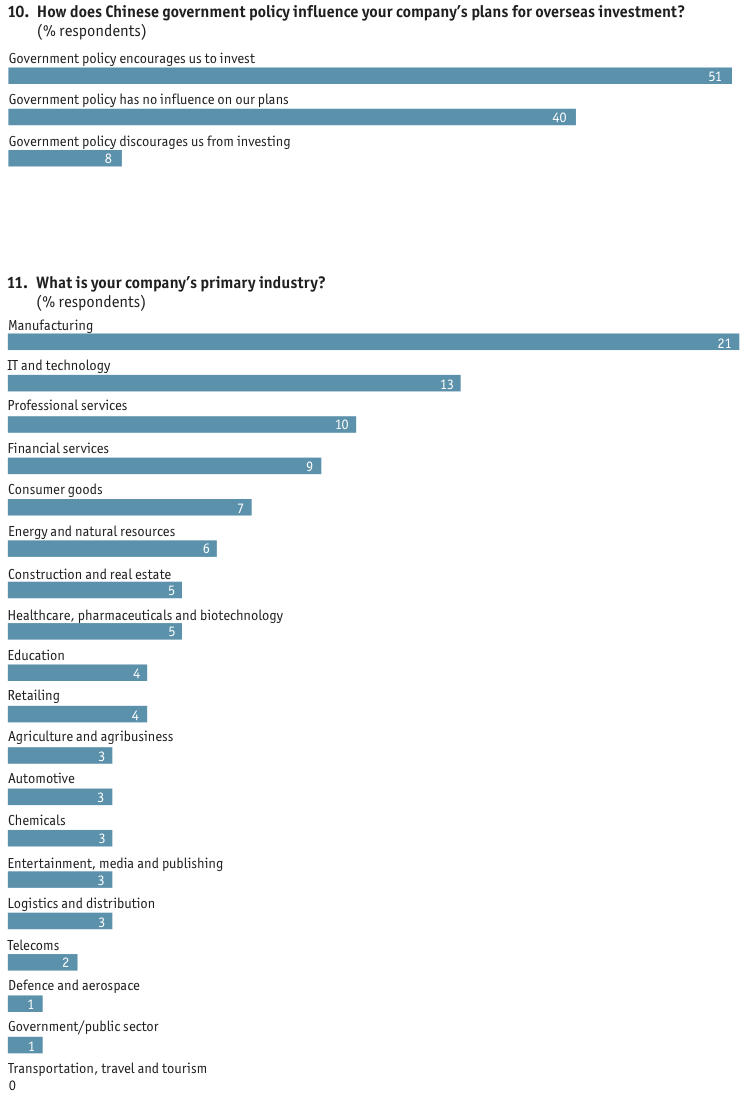

Some of these trends are bound to continue into the future, not least because they are a response to China’s official ODI policy. This response, moreover, is spearheaded by state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Since announcing the “go global” policy, the Chinese government has repeatedly loosened its regulations on overseas investments. Stated guidelines of the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) on ODI are that Chinese companies should invest in a feasible project in an economically and politically stable host country that has concluded a bilateral investment and taxation treaty with China. The investment should also carry benefits for the company and for China’s economy by either promoting Chinese exports, enhancing the firm’s technological capacity and research-and-development (R&D) activities, or enabling it to create and establish an international brand. All the official exhortation is definitely influencing corporate decisions: 51% of our survey respondents say it encourages them to undertake overseas investment.

This ODI strategy also entails plenty of financial incentives and support from central and provincial authorities, as well as state-owned banks. But while keen to encourage the acquisition of foreign assets, Chinese officials are also eager to avoid embarrassment and to ensure that acquisitions are in line with the country’s broader economic policies. Hence, all overseas investments by mainland-registered entities must pass through regulatory approvals.

Officials seem to lack confidence in the ability of Chinese companies, or at least certain types of companies, to manage acquisitions. As Wang Qishan, a vice-premier, speaking at a conference in 2009, told an executive from Hunan province who had asked the state to fund his company’s overseas expansion: “Do you have a handle on your own management capabilities? Have you analysed the cultural differences of the two sides? Do you understand the relationship between unionised labour and management in that place? If the other side’s engineers resign, are you really going to send people from Changsha [Hunan’s capital] overseas, and make the whole company speak Hunanese [the local dialect]? If you don’t know yourself and know your opponent, then this kind of confidence scares me.” Some analysts suggest that such caution on the part of the Chinese government (and its refusal to approve deals it does not like) is the main reason why crossborder M&A thus far (at least large deals) has been dominated by resources deals—coal mines are more straightforward to manage than international brands.

Struggles

Setting aside for a moment the ability of Chinese companies to manage acquired assets, are they successful in completing the deals they initiate? By and large, it seems that most deals that make it to the official offer stage do sign on the dotted line. Not all deals show up in official data. Some will have been conducted or at least attempted by two private entities, with no need to announce the results to the public. Others will not appear in data sets for a variety of reasons. But based on the available data for deals worth more than US$50m that we examined, the number of completed deals (172) far outnumbered those that failed. Among the 22 that did fail or were withdrawn, five did not receive regulatory approval (four of these were in the resources sector) but more (six) were withdrawn due to changed market conditions. For all the successful deals, however, there have been some huge disappointments, such as Chinalco’s bid to increase its stake in Rio Tinto, which have caused frustration in Beijing, to put it mildly (though a recent report on the Rio deal to China’s State Council blames market forces, not politics, for the deal’s failure and Rio Tinto and Chinalco subsequently have announced plans for a strategic partnership).

Undoubtedly, there are struggles that do not make the headlines. One Shanghai-based consultant who helps small to mid-cap companies to source deals in Europe, mainly in Germany, says that only about one-third of the deal-finding projects his company is contracted to work on are completed. The others fall apart for various reasons, including difficulties in finding the right partner or product portfolio or differing price expectations. But once a match has been found, the biggest reason for failure is timeline. “There are usually two or three competitors, either American or other European companies, and they are much faster and more experienced in negotiating and setting up financing,” says the consultant. China’s own regulatory hurdles are a particular problem in this regard, and for deals involving small to mid-cap companies state banks are said to take several weeks to conduct due diligence and risk assessment, while foreign competitors are likely to take a matter of days.

The fact that many of the large Chinese companies interviewed for this report (six out of 15) said that identifying appropriate targets is a major challenge in overseas M&A suggests that there is a lot of preliminary discussion before formal offers are made. As the following chapters discuss, once formal negotiations begin, lack of experience and the state-approval regime can put larger deals at risk in certain situations.

Chapter 2: Dreams versus reality

Faced with political scrutiny in some markets and difficulty in managing acquisitions, Chinese companies seem to be taking a step back, focusing on less ambitious deals

What is Chinese companies’ own take on all this? Do they see things as their government does? Do they worry about the problems encountered by some Chinese investors abroad? What are their greatest hopes and fears as they venture beyond the familiar confines of their home market? The attitude of most Chinese companies to crossborder M&A can be summed up as one of cautious opportunism.

The executives we interviewed are acutely aware of the friction some larger investments have caused and are concerned about the negative environment this has created. But less than half said that the friction would have a major impact on their company’s overseas investment plans, and any consequence would most likely involve avoidance of certain markets. Protectionism was also cited by only 24% of respondents who took our survey as a worry—which suggests that Chinese companies are less concerned than their counterparts and advisers overseas, as we discuss later in this report.

What do Chinese companies see as the root cause of the not-always-welcome political reception abroad? While six of our interviewees pointed to nationalist or protectionist sentiment, five also cited lack of understanding of Chinese business among foreigners—a point amply backed up by our interviews in target markets.

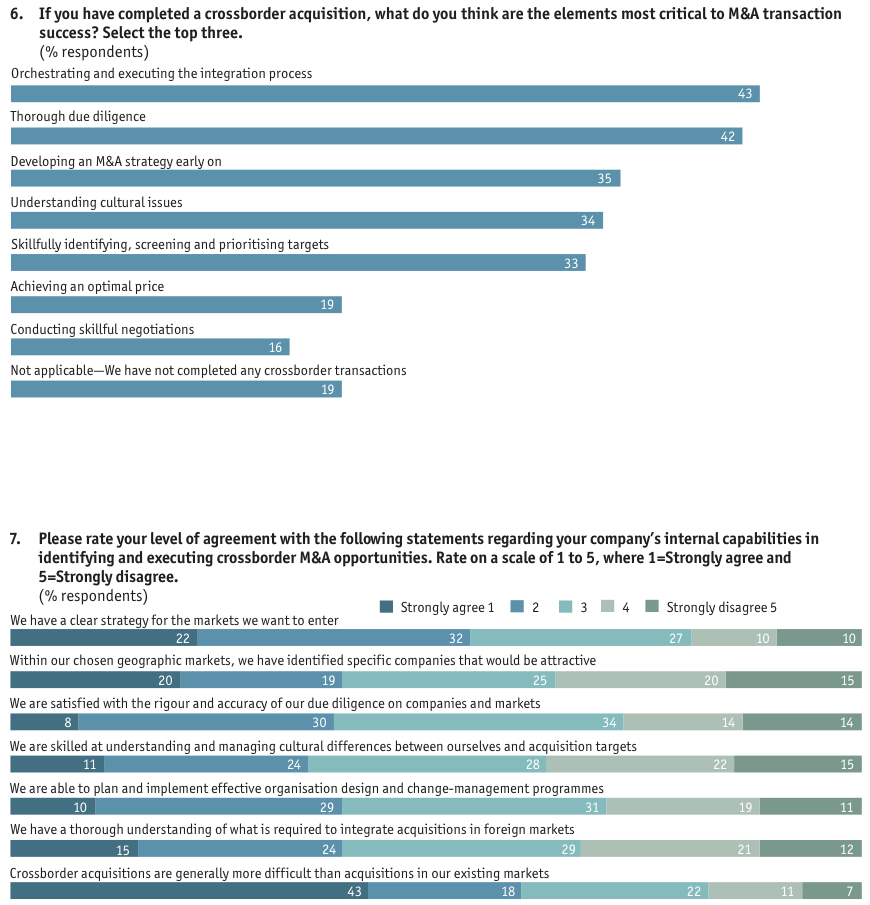

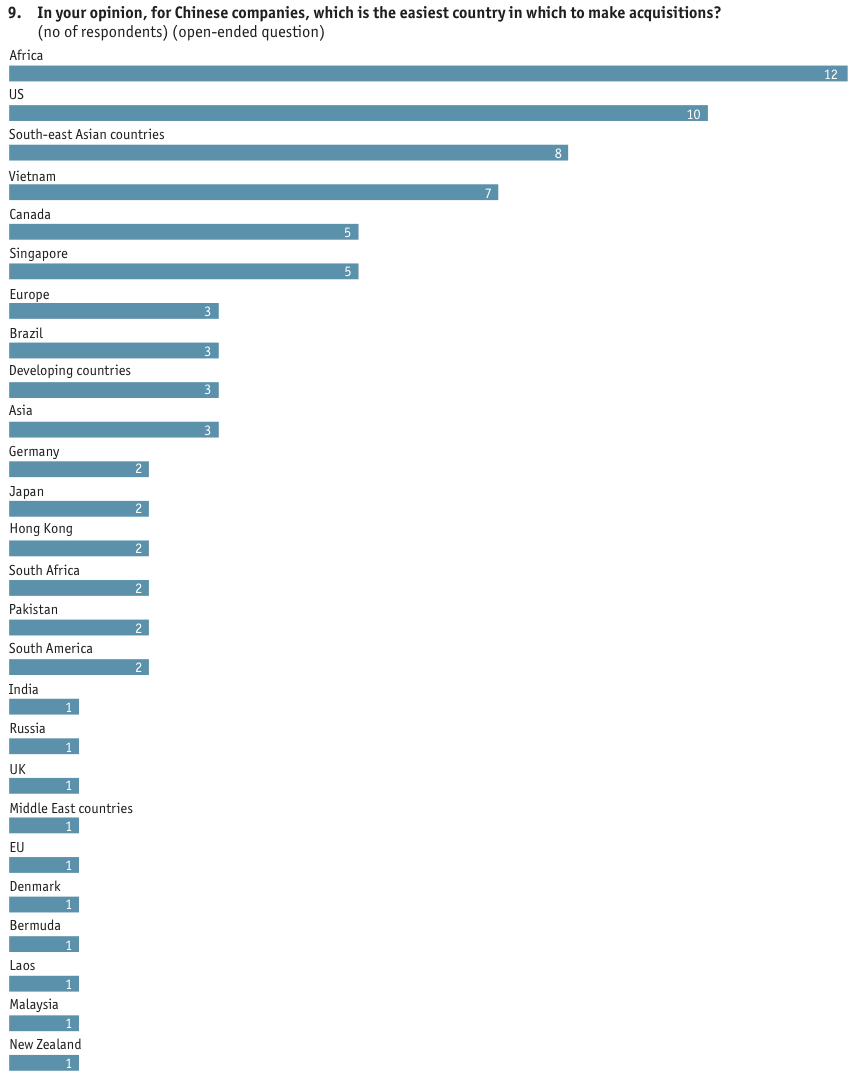

One of our interviewees describes the current dynamic this way: “We do see an anti-Chinese sentiment developing in certain markets. As China becomes economically stronger, there is bound to be a sense of fear among countries that are current and former economic powers.” Another interviewee singled out the US as one country it would avoid because of perceived prejudice there against Chinese investors; in our survey, too, 49 of the 110 respondents picked the US as the hardest country in which to make acquisitions, far ahead of any other countries listed. Still, 39% of respondents said they would focus their outbound investment on North America, just behind the number (42%) saying they would focus on Asia. Africa was viewed as the easiest country in which to conduct M&A.

But other Chinese companies interviewed, particularly in the natural-resources sector, are more understanding of foreign concerns about them. According to an executive of Sinochem, “when it comes to natural resources, national protectionism rises naturally—especially as the world starts to realise that resources are scarce.” And the burden of countering foreigners’ negative perception of Chinese intentions ultimately lies with Chinese companies, argues an executive of Chinalco. “To become an internationally recognised company, we need to win the trust of foreigners,” he says. “It’s not an easy process, but we need to communicate on all fronts—politics, economics, diplomatic and business.”

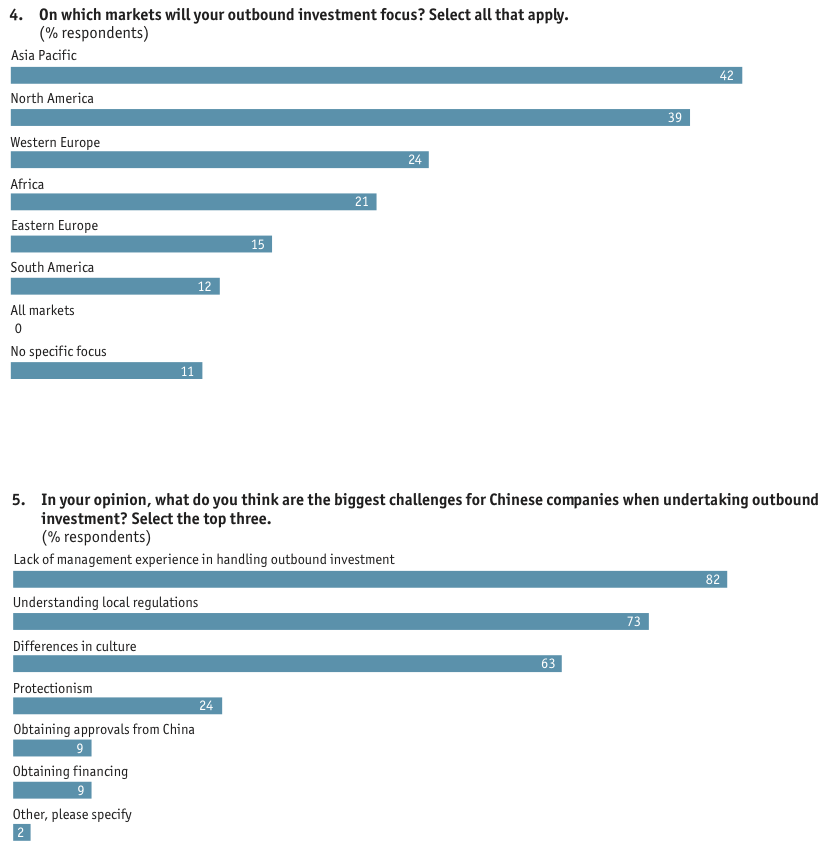

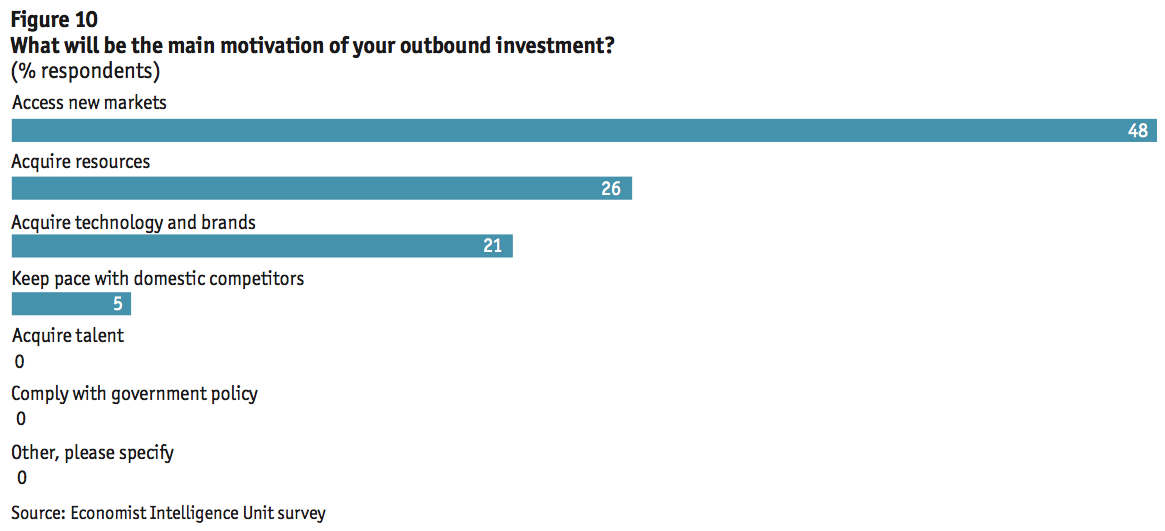

Reaching a common vision of integration

Chinese companies investing abroad certainly should redouble their PR efforts (as the next chapter discusses in more detail). But that is only half the battle. As important is better preparation for actually managing the foreign entity after an acquisition. At heart, M&A is not a politically driven endeavour: it is absolutely critical to get the business aspects of it right. The most seasoned Chinese executives know that. In our survey, 85% of respondents who have completed a crossborder acquisition said orchestrating and executing the integration process (43%) and thorough due diligence (42%) are the most crucial elements in the success of the project. Failure to fully think through a vision for the acquired entity, or to gain agreement on this vision with existing management—which, our interviews show, most Chinese acquirers hope to keep—are common mistakes.

Suntech Power’s experience with its first overseas M&A deal is illustrative of how difficult it can be to achieve a shared vision. In 2006 the Chinese solar-panel maker bought MSK, its more advanced Japanese rival. The aim was to smooth its entrance to the notoriously difficult Japanese market. To meet Japanese demand for high-end solar panels, Suntech continues to manufacture them in Japan, but it moved the production of low-margin panels to China. The existing Japanese senior managers of MSK opposed a strategy that must have looked to them like asset stripping. So Suntech went through several CEOs and CFOs before it found a Japanese team who saw eye-to-eye with its vision of market differentiation.

Changsha Zoomlion Heavy Industry Science and Technology Development, which acquired Compagnia Italiana Forme Acciaio (CIFA), an Italian company and one of the world’s three biggest concrete-equipment manufacturers, in 2008 (see Constructing a global giant), worked at achieving a common vision from the outset. According to Zhan Chunxin, chairman and CEO of Zoomlion, as well as a clear goal a successful acquisition requires realistic analysis of the advantages to both the acquiring company and the target company. “We must know what the point of the acquisition is,” says Mr Zhan. The usual strengths of Chinese manufacturing companies are high capacity and low manufacturing cost, “yet if the target is also a company with high capacity, the advantages of China’s manufacturing cannot be realised,” he says. Some Chinese companies have transferred entire production lines back to China, says Mr Zhan, but he believes that this is a big mistake. “In this way, there are no complementing advantages, as the target company has high costs and much difficulty in cutting the workforce.”

Finding targets that make sense has been a major challenge, according to some of the Chinese executives interviewed for this report. While the issues in target identification vary by industry, in the current environment of financial distress it is more a matter of being spoilt for choice—or so it might appear. The truth is that the risk of choosing the wrong target is increased by the temptation of lower prices and previously unavailable assets. In the natural-resources sector, it is also a question of which acquisitions are likely to be approved by regulators. Our survey results suggest that Chinese companies may have been ill-prepared for the opportunities thrown up by the financial crisis—only 39% said they had identified specific companies that would be attractive to them within their chosen geographic markets.

Constructing a global giant

Changsha Zoomlion Heavy Industry Science and Technology Development, a leading engineering-equipment maker, had already completed two acquisitions within China when it was approached as a potential buyer for Compagnia Italiana Forme Acciaio (CIFA), an Italian company and one of the world’s three biggest concrete-equipment manufacturers. According to Zoomlion’s chairman and CEO, Zhan Chunxin, the company had been actively looking for overseas targets. Specifically, it was looking for companies in the same product lines as Zoomlion that could offer the Chinese company technology, management expertise and access to overseas markets. CIFA, with its 80-year history and market position, certainly had a lot to teach. “With fewer than 1,000 employees, CIFA has revenue higher than the 3,000-employee concrete-equipment department of our company,” says Mr Zhan. CIFA’s brand and marketing channels in Europe and Middle East were also widely respected.

Zoomlion and CIFA completed the deal in 2008 and, while CIFA continues as a separate entity, both are seeking synergies. Maurizio Ferrari, the former Italian CEO and chairman of CIFA, remains chairman of CIFA and general manager of Zoomlion CIFA Concrete Machinery Management Company. A committee consisting of Mr Zhan, Mr Ferrari and a board director at Hony Capital (a private-equity firm that is a joint investor) is the decision-making body. The CFO of CIFA took over as CEO of CIFA. The general manager of the concrete business department at Zoomlion was appointed as vice-president of technology R&D and is the main coordinator for exchanges between Italy and China. As Mr Zhan describes it, the company has established “a unified management system, a unified R&D platform, a unified sales system and a unified production collaboration system”. At the management level, the Chinese and Italian sides collaborate via weekly teleconference.

The new entity has started to try to lower costs via combined purchasing and moving some parts manufacturing to China. The strategy from the outset has been to continue with both brands, leveraging CIFA’s distribution network and allowing the combined entity to tap different segments within each market.

Mr Zhan believes that despite the differences in language and culture, the two sides have the same goal and similar views on running a company, such as cost management, sales strategy, channel management and R&D. The critical factor is understanding each other’s point of view and agreeing on overall strategy.

Management shortfalls

Chinese executives also worry about their lack of overseas experience. In our survey, 82% of respondents identified lack of management expertise in handling outbound investment as the biggest challenge for Chinese companies. Only 39% feel they know what is required to integrate a foreign acquisition. To give an extreme example, management of one Chinese manufacturer interviewed felt it had no choice but to retain temporarily the management team of an Australian supplier that had bankrupted the company because it could not immediately run the foreign acquisition itself.

It is not surprising that many acquirers hope to make up for their management shortfalls by retaining the leadership of the companies they acquire. While primary motivations for their acquisitions are obvious—to secure resources, market access or technology—the larger companies interviewed for this report are clear that they are aiming for much more than bolt-on assets. The majority of the companies interviewed said that they track the performance of their acquisitions in terms of the value added to the entire company. An equal number said they leave the existing management in place at their acquired companies. The ultimate aim of their integration, many companies said, is to use the acquisition to “help the parent company learn”.

Beyond its broader strategic aim of a secure supply of resources, Chinalco’s attempt to raise its stake in Rio Tinto was motivated by just this aim. “What we wanted was to learn from their management system, corporate governance, experience, etc,” says one senior executive at the Chinese firm. “In a nutshell, we wanted to learn best practices and a larger stake and a strategic partnership would have given us more access to learning. We admit, one of the major challenges we face is our management capabilities. We know that we still lack sufficient talent—managers with international perspective who can work in overseas markets and who will be able to exchange management ideas with their counterparts.” In return (aside from financial considerations), Chinalco had planned to help Rio Tinto access the Chinese market.

The difficulty for Chinese companies will be in structuring their deals to ensure that they get what they are seeking—whether it is learning, or synergies. It is well known that M&A is a difficult process for any company of any nationality, and that many deals fail to achieve their intended results. One of the studies conducted on the topic showed that of over 200 major European M&A deals, nine out of ten fell short of their objectives. The difficulties are compounded when deals take place across borders, where the issues of culture, different management styles and regulations can aggravate an already delicate process. A global survey of 500 executives with significant M&A experience found, not surprisingly, that 70% of companies believed crossborder M&A deals are harder than domestic ones.

Yet Chinese executives seem to be less apprehensive about crossborder M&A than their foreign counterparts. In our survey, only 61% of Chinese companies agreed that crossborder acquisitions are generally more difficult than acquisitions in their own markets. Moreover, Chinese companies may underestimate the importance of prior planning. Only 16% identified skilful negotiating as a critical factor in the success of an M&A deal. Perhaps this is a matter of experience—or lack thereof.

Among the other challenges to crossborder M&A, our survey respondents identified local regulations (73%) as the second biggest problem behind a lack of management experience, followed by cultural differences (63%).

Starting small

How can Chinese companies overcome these challenges? The simple answer may be to begin with more modest ambitions. It is worth pointing out that this is how many of the world’s largest MNCs initially enter new markets—via partnerships or alliances that help them learn their way around. While it is too early to call many Chinese acquisitions a success, there are some examples of how the deal-making process can be made smoother.

One solution is to start small and build on relationships. Sinosteel, for example, began its relationship with Midwest Corporation of Australia with a joint venture in 2005, and took over the Australian company in 2008. What was termed a hostile takeover at the time was in reality the push by one major shareholder for a higher price. In the end, Sinosteel did improve its bid and gain the endorsement of the Midwest board. According to a senior executive at Sinosteel, top management at the company regards its long- term co-operation with Midwest—ie, its familiarity with Midwest’s management and culture—as the most crucial factor in the success of the deal.

Our data analysis and interviews all indicate that Chinese acquirers in the past have tended to aim for controlling stakes in their ventures. But potential future investors seem to be taking a step back from this approach. Of the 60% of our survey respondents who said they were definitely or likely to make an overseas investment, only 27% said they would do so through acquisitions, and another 18% said they were interested in taking minority stakes in established companies. Only 5% said they would prioritise greenfield investment, while 47% would prefer to strike either joint ventures (29%) or alliances (18%). The fact that almost half of those interested in investing abroad would seek partnerships strongly suggests that many Chinese companies are more vigilant about the potential risks of their foreign forays. As only time and experience will make Chinese executives more effective working in a foreign environment, taking minority stakes in overseas entities is expected to rapidly gain favour (based on its filing with the US Securities & Exchange Commission, this has been the approach largely taken by China Investment Corporation or CIC, China’s sovereign wealth fund, which with a few exceptions, has bought very small stakes in listed companies). A prominent mainland Chinese investment banker says Chinese companies are mindful of increasing protectionism abroad and see no point in going for big stakes when they know they will be rejected. Executives of both Zijin Mining and China Minmetals also say that they would advise other less experienced Chinese companies to take a low-key approach and find foreign investment partners in their initial crossborder forays. That would minimise the downside risks of going for full control—namely, raising concerns about their overtures among both the public and regulators, and losing key staff who will take valuable knowledge with them.

The more cautious approach may be highlighted by Beijing Automotive Industry Holding (BAIC), which has purchased Saab’s core technology (but not its brand and plants) from the Swedish carmaker’s bankrupt parent, GM of the US. According to a senior executive at the company, BAIC had been eyeing foreign acquisitions for a long time, and it figured Saab was just the kind of target it had been looking for. The Chinese carmaker is mainly interested in upgrading its own cars for the domestic market, and believes that incorporating Saab technology will impress Chinese drivers who are often dismissive of domestic brands. This is why “we have brought a lot of Swedish engineers to China”, says the BAIC executive. The deal also aligns perfectly with the Chinese government’s goals, and avoids the thorny issue of restructuring the ailing Swedish icon and managing the brand in international markets. Of course, there are exceptions to the rule—indeed, BAIC’s cautious plan contrasts sharply with the private-sector Geely’s bid for Volvo in its entirety.

Paying too much?

Along with lack of experience, some Chinese executives, especially those who had struck deals just prior to the onset of the financial crisis, are concerned that they may be paying too much for deals. For COSL, a petroleum services firm, its bid in 2008 to acquire Awilco Offshore, a Norwegian oil-drilling company, almost fell apart at the 11th hour because the two parties could not bridge a small gap in asking and offering prices. The deal took place against the backdrop of record oil prices, and the negotiations dragged on. In the end, COSL feels it paid slightly more than it had hoped to in order to close the deal (and in the process it dropped the two international private-equity partners who had hoped to be co-investors).

There were more than purely business factors at play, however. COSL says it considers about 2-3% of the final agreed price a “Chinese SOE premium”. This is the extra amount that some foreign sellers demand because they are worried about the lack of transparency at many state-owned Chinese companies and their ability to run the acquired enterprise afterwards. For their part, Chinese executives say they are well aware that foreigners often imagine some nefarious state-directed plot in their M&A initiatives. And they know this makes success that much harder to achieve.

Lenovo-IBM marriage—a work in progress

When Lenovo announced that it was buying IBM’s iconic personal-computer (PC) division for US$1.75bn in 2005, it put the rest of the world on notice that Chinese companies were about to become a much bigger presence in the everyday lives of foreign consumers. Overnight, the deal transformed China’s biggest PC-maker into one of the most-recognised Chinese brands from Beijing to Boston. Pundits lauded Lenovo’s bold takeover as heralding a new era of truly global Chinese multinationals. Five years on, however, the union remains far from perfect: “Time will prove whether the deal was a success,” says Fu Junhua, a senior Lenovo executive who was part of the IBM acquisition team.

By its own reckoning, Lenovo did not encounter many political problems during the deal-making phase. Ms Fu credits this to the compelling market logic of the deal—Lenovo was searching for a quick way to internationalise its business, and IBM wanted to divest from a loss-making division which was no longer a core business. Lenovo also enlisted the help of three well-known US advisers for strategy, financing and due diligence. And according to knowledgeable US observers, it helped that Lenovo was pursuing a friendly takeover and that the Chinese company let IBM take the lead in handling US regulators (in contrast, many in the US saw CNOOC’s failed attempt to acquire Unocal the same year as a hostile bid). “IBM really led the charge on all aspects of that transaction,” says a partner in a Washington-based law firm. “IBM took the lead in terms of the political dimensions, and the government was fully cognizant of the whole deal. The technology transfer was done carefully. There was just a tremendous amount of planning and preparation that went into the deal.”

Even so, some American critics questioned Lenovo’s motives at the time, and many US government agencies today reportedly do not buy computer products made by the company.

As for the integration of the two manufacturing operations, Lenovo believes it has gone relatively smoothly. For example, the company has merged component-purchasing efforts so that it has more bargaining power with suppliers. It has also trimmed overlapping personnel, reducing its overhead costs in 2009 to just 9% of overall expenses. And the company feels it has improved service for corporate customers of IBM’s former ThinkPad line of PCs by applying Lenovo’s intense retail ethos in China’s domestic market.

Lenovo’s integration team was led by a partner from one of its advisers and a partner from TPG, an American private-equity firm that was a financial player in the acquisition. The aim of using outsiders was to leverage their expertise in organisational restructuring, strategy setting and integration. The main post-merger challenge, perhaps unsurprisingly, has been reconciling the vastly different cultures of a Chinese and an American enterprise. As Ms Fu describes it, the goal has been to create a “globalised MNC culture”, meaning to take what is useful from both cultures. Lenovo hired William Amelio, a former IBM and Dell executive, as CEO of the merged entity, and he brought with him several executives from Dell. The result was a management team that included members from three different organisations—IBM, Dell and Lenovo.

There were inevitable differences in national culture. In one small illustration of this difference, Ms Fu says she was surprised to find that no one from the American side offered any help with relocation when she moved to the US to partake in the post-merger integration process; her Chinese colleagues never would have left foreign executives to settle in China on their own devices. But there were sharp differences in corporate culture as well. “It turned out that Lenovo’s culture and Dell’s are very similar, as both focus on speed, efficiency and results, whereas the IBM culture is much slower in terms of pace,” says Ms Fu.

Such cultural issues came to a head in early 2009 when, amid a sea of red ink, Lenovo replaced Mr Amelio with its Chinese chairman, Yang Yuanqing. Many foreign observers saw the move as an admission that Lenovo had failed to internationalise its management in one fell swoop as it had hoped. Lenovo’s Chinese executives reportedly did not warm to Mr Amelio’s attempt to impose his managerial style on the merged company.

Lenovo still hopes to create a new multinational culture that is truly global. The job of pulling off that tricky task now belongs to Liu Chuanzhi—founder of Lenovo who returned to the chairman’s position after Mr Amelio’s departure.

Chapter 3: Welcome or not? The view from overseas

Attitudes towards Chinese investment have warmed. But the risk of a backlash is ever-present.

The global financial crisis has raised China’s international stature in multiple ways. The continued strength of its economy, albeit fuelled by a huge stimulus programme and loose bank lending, has underscored China’s still massive growth prospects—in stark contrast to those of developed economies. And with more than US$2.4trn in foreign reserves, China’s seemingly limitless spending power is the envy of many Western countries, which are bracing for years of belt-tightening to put their financial houses in order. So it should come as no surprise that foreign businesses are more eager than ever to benefit from China’s strong growth.

Warmer attitudes to Chinese investment are evident today from New York to Brussels to Sydney. Says a managing partner at a large US private-equity firm: “Most sophisticated US companies would be very open to working with Chinese companies. China is the fastest-growing large market in the world, and US companies believe that helping the Chinese in this country is a very good way to build relationships that will potentially help them in China.” The prevailing view among suddenly cash-strapped Americans is summed up more succinctly by a US lawyer who advises crossborder buyers and sellers: “China needs to recycle the dollars, and we’re more than happy to take them!”

That is a sentiment shared in Europe, where economies have also been severely battered by the financial storm. “The crisis has dampened the anxieties about Chinese investment,” says Tomas Baert, an official at the European Union responsible for foreign investment policy. “Everyone is looking for cash and is very keen to attract funds from countries sitting on a lot of money.” Even in Australia, where the downturn has been much milder than in most developed countries and despite the kerfuffle over the rejection of Chinalco’s bid last year to increase its stake in Rio Tinto, Chinese investment is finding a more welcome reception. “Foreign capital is necessary for Australia to develop and grow resources,” says Owen Hegarty, a director of Fortescue Metals Group, which has sold a 16.5% stake to Hunan Valin for US$771m. “Traditional markets of the US, Japan and Europe are important, but China, India and Indonesia are the future. And the main game is China.” (Still, Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board or FIRB remains a source of frustation to Chinese investors; see Australia—fair?) Meanwhile, Canada has shown one of the most dramatic shifts from playing hard to get to bear-hugging China (see Canada—thawing relations).

In the US, too, there is a growing realisation that regulatory instruments, such as investment reviews by the US treasury department’s Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), need to be wielded judiciously. Advisers in the US are keen to point out that CFIUS is not a general screening board for foreign investment but looks only at deals that might have national security implications. Only a fraction of incoming investments—believed to be less than 10%—fall under CFIUS purview. “Companies buying assets in the US linked to national security should be prepared to work with the US government to show that the deal is not going to harm national security,” says Clay Lowery, who chaired CFIUS during the Bush administration. “But the US is not looking at every deal coming into the country. If a Chinese company wants to buy a chain of restaurants, that shouldn’t be a problem. There is a recognition that the government needs to make sure it protects national security, but in a way that doesn’t harm foreign investment into our country.”

Proof that more favourable views of Chinese investment are in fact facilitating more deals is in the numbers—in the face of the worst global business environment in decades, Chinese entities still managed to generate a record number of M&A deals in 2009.

Canada—thawing relations

There has been a sea change in Canadian attitudes to Chinese investment since public protest forced state-owned China Minmetals in March 2005 to withdraw from negotiations to take over Noranda, then one of Canada’s largest mining and metallurgy companies. That proposed deal for a leading firm in Canada’s important natural-resources sector touched a nerve among Canadians, already fearful that the corporate sector was being “hollowed out” through foreign acquisitions. That it was being made by a state-owned enterprise (SOE) from communist China led to fears that the new owner would use Noranda’s assets for political rather than economic ends, and strip jobs and expertise from Canada. The Canadian Auto Workers, the country’s largest private-sector union, spoke for many in October 2004 when it protested that Canada, used by the former colonial power Britain and later by the United States as a source for raw materials, “is becoming a colony once again, and China is the coloniser”.

Yet 2009 saw a number of large Chinese investments in Canada’s resource sector with barely a whisper of complaint. They include the US$1.5bn acquisition by China Investment Corporation (CIC) of 17.2% of Teck Resources, a top producer of zinc, copper and metallurgical coal, and the US$1.7bn purchase by PetroChina International Investment of a 60% interest in two projects in the Alberta oil sands from the privately held Athabasca Oil Sands.

According to interviews with counterparties and advisers, the warmer reception Canada is giving to investment from China is not only due to changes in the Canadian economic and political context, but also to a growing sophistication among Chinese investors on what deals to propose, how to structure them, and how best to navigate Canadian business rules, regulations and etiquette.

What’s changed in Canada

Even as Minmetals withdrew from the Noranda talks, other foreign purchasers were snapping up large Canadian resource firms in the midst of what was then a global commodity boom. Noranda itself was purchased by Swiss-based Xstrata, nickel giant Inco was bought by Brazil’s Vale, and Alcan was acquired by the British-Australian conglomerate Rio Tinto. The Chinese became one of many aspiring purchasers and not the only one using SOEs to make acquisitions. “Canadians were far more fearful and concerned five years ago than they are today,” says David Emerson, a former industry and foreign affairs minister who now sits on the international advisory board of CIC. “People are starting to come to terms with the fact that it is a global economy and that there’s got to be engagement in the level of direct investment.”

The global economic crisis and protectionist backlash in the US, which has been felt most keenly in its largest trading partner Canada, has also increased the allure of investment from China. “It’s provoked a rethinking of North American integration,” says Peter Harder, a former senior federal bureaucrat and now president of the China-Canada Business Council. While Canada remains tied to the US and Mexico through the North American Free Trade Agreement, the drop in American consumption and the “Buy America” provisions occasioned by the economic slump have reminded Canadian business that “we shouldn’t just put all of our eggs in this North American basket”, he says.

Chinese investment also looks attractive to resource companies looking to finance large, capital-intensive projects and unwilling or unable to access bank financing. To build a mine can cost US$3bn, says Philip Smith, deputy head of global investment banking at Scotia Capital who has worked on a number of deals involving Chinese investors. Companies need to tap into sources of funds other than equity investors and pension funds in North America and Europe. “China has got a real glow to it,” he says. “There are a lot of companies that would love to have a major Chinese investor.”

Reflecting this shift in business perceptions, the Canadian government significantly changed its approach to China in 2009, with a string of ministerial visits capped by a bilateral visit to Beijing and Shanghai in December by Stephen Harper, the Canadian prime minister, who urged the Chinese to invest in Canada. Relations with China had been hampered by the government’s previous focus on human-rights abuses and by a change to the Investment Canada Act in September 2009 that inserted a new national-security provision in investment reviews. While not specifically aimed at China, it was interpreted as such by some investors. The approval of the PetroChina investment in the oil sands indicates that it need not be an impediment. During his visit to China, the Canadian prime minister also urged both sides to revive negotiations, started in 1994, for a bilateral Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement.

What changed in China

If the failed attempt to acquire Noranda was an example of what not to do, the investment by CIC in Teck Resources was the opposite. Taking 17.2% of the company, rather than a controlling stake, dampened any criticism that China was taking over one of the few large resource companies still in Canadian hands. Such PIPE (private investment in public equity) transactions are increasingly popular, says Philip Brown, head of mergers and acquisitions at Torys, a law firm, which acted for CIC in the Teck deal. Such transactions usually do not trigger an investment review because they do not involve a change in control. The US$500m investment by CIC in SouthGobi Energy Resources of Canada was a similar type of deal. Chinese investors are “staying under the radar screen” by not taking a controlling interest, says Mr Smith of Scotia Capital.

The investment banker says that the deals that seem to work best for Chinese investors, which tend to be SOEs, are ones involving bilateral negotiations rather than auctions. The methodical, process-driven approach by the Chinese is best adapted to bilateral negotiations. “They’re just not accustomed to competitive auctions on an extremely accelerated timeline, like we often see with mining and oil and gas companies right now,” he says.

Canadians involved in overseas investment have noted increased efforts by Chinese companies to become familiar with Canadian companies and with the rules, regulations and etiquette governing investment in Canada. Sinopec, CNPC and CNOOC have all become regular visitors to Canada.

Ron Vance, senior vice-president of corporate development at Teck Resources, says the Teck deal with CIC went smoothly, in part because CIC deal team members had a good understanding of Western business practice and what was important to Teck. One of the big hurdles for SOEs that do not trade on a stock exchange is to understand that Western CEOs must keep in mind the interests of all stakeholders, including shareholders. In the Teck deal, this was not an issue. “Our experience would suggest that there may well be a much keener appreciation for our cultural issues by them than perhaps our appreciation of their cultural issues,” says Mr Vance.

That understanding is not always so complete, says one investment banker who has been involved in past deals. The Chinese side did not always understand that once a deal had been reached and agreed, the terms were not open for renegotiation. Once they have done a few deals, they understand, he says, but in the meantime “it can be a bit frustrating” for the Canadian side.

Outlook

Some sensitivity to Chinese investment in Canada remains, but less than five years ago. Kenny Zhang of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada cites natural resources and high-tech as two areas where a large investment might encounter difficulties. Others cited uranium and military goods and services. Mr Zhang, who has done a survey of Chinese investment intentions with regard to Canada, notes that most respondents said energy and natural resources were the most promising sectors for investment, but some Chinese companies are also interested in agribusiness, information and communication, and biotechnology. Among the least attractive investments, according to his survey, was the beleaguered car and car-parts manufacturing industry.

As long as Chinese investors continue on their current path of cautious, modest investment in sectors where they are not trying to “fundamentally rock the boat”, then the investment relationship will keep getting stronger, says Mr Emerson. “I think they have to be cautious in what their candidates are, the investment targets, and how far they will go in certain sectors,” he says. “I think they understand that as well.”

One issue looming on the horizon is reciprocity. If Canada is open to Chinese investment, it will expect China to reciprocate and not close off areas it considers strategic. The Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement may help in this respect, but full reciprocity will require strong political backing.

Guilt by association

Chinese companies’ global expansion, however, still faces numerous potential pitfalls. Western investment review bodies such as CFIUS, FIRB and their Canadian and German variants are meant to vet all sensitive inward foreign investments regardless of their countries of origin. But the fact remains that Chinese (as well as some Middle Eastern) investments do invite more scrutiny than, say, those from the UK or France. This is largely because of a reflexive distrust of enterprises with ties to the Chinese government. “Companies that are listed on overseas exchanges are viewed differently,” says one consultant in Australia. “But if they are partially listed on Shanghai and otherwise locally owned, politicians are smart enough to know they are still really [Chinese] government controlled.”

As experienced Chinese investors are already aware, there is a lack of understanding of Chinese business in general and state-owned enterprises in particular. Participants in the M&A process in countries such as Australia blame this on China’s lack of transparency, but also ignorance on the part of the foreign public. “Australians are way too convinced there is one large conspiratorial China Inc, and this gets in the way of deals being done,” according to Nick Curtis, executive chairman of Lynas, an Australian mining company.

Indeed, such concerns have contributed to the sinking of a number of past deals, including China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group’s plan to take a majority stake in Lynas in 2009. FIRB’s rejection was ostensibly on the grounds that China already controls over 90% of the world’s rare-earth minerals, which are used in a variety of technological devices. But insiders say it was the result of political tensions between Australia and China at the time and heightened public sensitivities to Chinese investment in the country’s resources. FIRB also forced China Minmetals to restructure its plan to acquire OZ Minerals so that a mine inside a weapons testing area was excluded. In the US, too, a controversy over Huawei Technologies’ alleged ties to the People’s Liberation Army forced the Chinese company to drop its 2008 bid to acquire 3Com, a telecoms-equipment maker.

These failed deals show that, at the very least, Chinese companies must do a much better job of communicating to foreign government officials—and the public—what the economic rationale for the transaction is and how market factors, not geopolitics, are driving it. “Politicians and policymakers respond to the public—and the public thinks China is run by a central committee,” says Paul Everingham, a Perth-based public-affairs consultant. “In order to satisfy the Australian public, Chinese companies may do well to provide clarity and transparency around who they are, who makes the decisions and why they are seeking the investment. There are quite a few examples where Chinese entities have come into the Australian market, paid above the market price for an asset, and this leaves many Australians wondering why they want the asset that badly. Australians want reassurance on how any deal is going to be structured, how the company will be managed post-investment and the longer term plans for the asset. Unfortunately, to date the public have not got the full story.”

Several Australian advisers, including a former Treasury official, point to Chinese investors’ tendency to use lawyers to represent them before FIRB as a possible source of tension. “This is a litigious, aggressive approach,” says one. “Foreign investment approval is not meant to be a litigious process. It’s a decision made in Australia’s national interest.”

While legal or other professional representatives can seem a safe bet when you are unfamiliar with the language or culture—and they certainly have a role to play in the M&A transaction process—deal advisers say that Chinese companies also need to use their own staff to present their motives and objectives. Advisers in the US tell a similar story. “Unfortunately, oftentimes US policymakers focus on high-profile deals, and they will think of Chinese companies as a monolithic block, rather than the individual companies themselves,” says Nancy McLernon, president and CEO of the Organization for International Investment, based in Washington, DC.

Aside from genuine concerns for national security, Americans are very sensitive to state ownership and any unfair advantage this might confer on Chinese SOEs. “The competitiveness issue resonates quite a bit (on Capitol Hill),” says Ms McLernon. “When you are competing against a company that is seen as having an advantage, such as financial support from a home government, it can raise some political concerns beyond national security.”

Tougher than the regulator

This means that deals that are not security threats and otherwise pass muster with CFIUS—or indeed do not even face CFIUS scrutiny—can unravel because of negative public perceptions. “Beyond CFIUS, we have seen, with DP World (DPW) and with other deals, that other players in the system can generate a heck of a lot of issues that can make it untenable for the company to go forward—which suggests having a broader outreach strategy than just a technical CFIUS filing,” says Mr Lowery, referring to the company owned by the Dubai government. DPW’s bid to buy the port management businesses at six major US seaports was withdrawn after it was blocked by the US Congress in 2006, despite having the support of the then-president, George W Bush. The port management companies had come into DPW’s hands via its acquisition of a British firm, Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O). While Congress’s opposition was ostensibly on national security grounds, it was persuaded to take up a review of the deal by a lobbying campaign funded by one of P&O’s American joint-venture partners which did not support the takeover and had exhausted all legal options to stop it.

The lesson of DPW is that buyers who are going to face regulatory scrutiny (and hence the possibility of unwanted publicity) need to take the regulator’s views into account when formulating the deal and make sure to get the signoff from all stakeholders—politicians, media, employees, customers, partners, etc—before it goes to the regulator. A major reason why the 3Com deal caused so much controversy was that Huawei first negotiated the deal and then sought to address CFIUS’s concerns. Observers agree that Huawei got the sequence wrong. “If Chinese companies view the regulatory review as separate from the deal structure, that’s a recipe for disaster,” says a Washington-based lawyer involved in such deals.

An example of how to ensure a smooth passage is provided by InBev’s purchase of iconic American brewer Anheuser-Busch. There were no national-security issues, but there was a high risk that patriotism might ignite a public backlash against the sale. According to one observer, before the transaction went forward InBev’s CEO went to Capitol Hill and talked to many people, explaining the reason for the acquisition and InBev’s post-acquisition plans. “That’s an obvious point, but still companies think they can fly below the radar, or think that because there are no national-security concerns they don’t have to worry about anything,” says Ms McLernon. “Those companies are making a mistake.”

The tricky issue of technology

Even where no real national-security issues exist, Chinese companies should be aware that they will continue to encounter significant foreign resistance to deal-making in certain sectors—especially, technology. At the behest of their government and of their own volition, Chinese companies have fanned out to advanced countries in search of technologies that will help upgrade their low-cost, low-skill manufacturing industries. For example, both BAIC and Geely say gaining access to foreign technologies to improve products at home is part of their long-term business strategy.

As China’s economic power grows in leaps and bounds, however, foreign firms are understandably becoming less willing to share technologies with their probable future competitors. This is potentially a much bigger challenge for Chinese companies than allaying foreign governments’ national-security concerns (which will persist). Many US companies believe that Chinese partners will not respect intellectual-property rights (IPR) and are fastidious about including tight safeguard provisions in agreements with Chinese counterparties. For their part, Chinese companies seem keener to deal with less uptight Europeans, in their perception, than haggle with IPR-obsessed Americans. The prevalent view in China is that Europe has more technologies of interest to Chinese companies than the US anyway, observers say.

Germany and the Scandinavian countries, in particular, are favourite hunting grounds for manufacturing-related technologies. Suntech Power, for instance, has acquired a German company to enhance its solar-panel manufacturing capabilities. And of course, both Saab and Volvo—BAIC and Geely’s targets respectively—are based in Sweden. Chinese companies are keen to buy German machinery and equipment manufacturers, as well as car-component makers. The sellers are usually small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that form the backbone of German industry. They are already heavily export-oriented but need capital to fund further development.

As many would-be Chinese buyers have found out, however, these types of companies are not willing to sell to just anyone. Chinese companies that are trying to take controlling stakes in these companies are increasingly encountering resistance from their German owners, who fear that the Chinese will cherry-pick their best assets for removal to China and fire most of the workers. Many of these firms are family owned and not keen to risk the livelihood of the next generation, either in their family or community. Some German companies are now introducing stipulations into their M&A agreements that the Chinese acquirer commit to keeping German facilities running for a specified period of time. In Sweden, too, the local press have carried reports of Volvo union members’ scepticism that the Geely takeover will not jeopardise their jobs, despite the Chinese carmaker’s public assurances that it does not plan to relocate Swedish plants to China. Zoomlion could have faced similar issues when it bought CIFA in Italy, but its advisers anticipated the concerns and were able to allay fears through a PR campaign. When Zoomlion executives visited Milan, Mandarin Capital Partners, a private-equity firm involved in the acquisition, organised local media interviews to help communicate with local unions. “They [the unions] didn’t know us,” says Mr Zhan, Zoomlion’s chairman and CEO. “The coverage helped as we promised not to lay off workers or move the whole plant back to China. We explained that’s not our goal.”

A related concern for foreign sellers is the perception that Chinese companies do not “get” the importance of quality. German (as well as Japanese) businessmen, in particular, have built their reputations on superior-quality products. So when they hear Chinese executives talk about how moving production to China will lower costs by one-quarter or one-third, they worry that quality—and the hard- earned reputation of their products—will inevitably suffer.

Such differences in perspective point to the myriad gaps between the business cultures of China and other countries. And this can throw up serious problems both during the negotiation of an M&A deal and after the transaction. Operating in a high-octane, high-growth economy, Chinese executives, at least at smaller, private firms, are accustomed to fast, flexible decision-making and are focused on short-term returns. “They will shut down one operation to pursue something that looks more profitable at the drop of a hat,” says one German deal adviser. “It’s hard for the inflexible German workforce, which has three-year plans and targets.”

With larger Chinese firms, the buying process can be painfully slow. According to some advisers, Chinese buyers tend to want to make conditional offers and then later slow down the process by negotiating over price, a complaint heard in both Australia and Canada. They also tend to perform due diligence after they have agreed a price. “This is worrying for Western vendors,” says an Australian investment adviser. Despite their reputation as tough negotiators, Chinese businessmen themselves seem to downplay the importance of price in M&A. Only 19% of our survey respondents who have completed crossborder acquisitions say that achieving an optimal price is a critical element of a successful deal (though as discussed earlier, experienced players have become concerned that they are paying too much for deals).

At heart, these issues arise because Chinese and foreign businessmen really do not know each other and each other’s business modus operandi very well. Foreign counterparties and deal advisers interviewed for this report all raised this issue, noting that it is a problem on both sides. But as it is Chinese companies that are going knocking on foreign doors, their executives carry the bigger burden of adjustment. As mentioned earlier, many already know that: 63% cited differences in culture as the biggest challenge in crossborder M&A. At the same time, though, only 35% say they are skilled at understanding and managing cultural differences.

One obvious source of such a worry is lack of experience. Over time, however, some improvements will occur naturally as Chinese executives gain more exposure to the international business environment, and as more conclude M&A deals. To build trust and understanding faster, however, Chinese companies could intensify their efforts to communicate better, going the extra mile to explain how business is done in China and to increase the transparency of their management decisions. Our interviews with Chinese companies suggest that the starting point for such a reaching-out exercise ought to be with their existing foreign joint-venture partners or suppliers. For example, in order to maximise the benefit of an equity tie-up with Cathay Pacific of Hong Kong and to try to understand its operating environment, Air China has put in place an exchange programme for mid-level managers. Sharing the management and operational experiences is an obvious “win-win” strategy, says a company executive.

Australia—fair?

Chinese investors are more than a little confused—and irked—by the seemingly inconsistent rulings of Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) over the course of 2009 and its general lack of commercial sensitivity. After government concern over Chinese investment in resources was stoked by Chinalco’s bid to raise its stake in Rio Tinto from 12% to 18% (Rio management, not FIRB, turned down the bid), FIRB rejected China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group’s plan to take a majority stake in Lynas. But it subsequently approved Yanzhou Coal’s A$3.5bn (US$3bn) takeover of 100% of Felix Resources and allowed Guangdong Nuclear Power Holding Corp’s 70% stake in uranium explorer Energy Metals.

The head of FIRB, Patrick Colmer, in a speech to a Sydney conference focusing on China-Australia business in September 2009, shocked many by seeming to set out limits for investment by China’s SOEs in the Australian resources sector. The Foreign Acquisitions & Takeovers Act (FATA) states that individual foreign buyers need approval to acquire more than 15% of an Australian company, or 40% if there is more than one buyer. Applications may be refused if they are deemed to be against the national interest. Reviews are a matter of policy, rather than law. But just what will be approved and what will be rejected? Mr Colmer seemed to say at the conference that stakes in Australian mining companies by Chinese SOEs should be capped at 15%, and that stakes in greenfield ventures should be no more than 50%.

Yet the Yanzhou and Guangdong Nuclear deals clearly do not match those criteria. According to one consultant, “The order from on high is that nothing over 50% ownership will be approved, preferably nothing over 40%—as long as the company in question is not about to go broke.”

It seems doubtful that Mr Colmer’s comments indicate official FIRB policy, as they have not been published on FIRB’s website nor has there been an official statement since the conference. Mr Colmer declined our request for an interview. On the surface, FIRB’s decisions do seem to be policymaking on the fly and somewhat reactive to public opinion. But they do give some indication of how Chinese companies can alleviate Australian concerns about investment in the resources sector.

Avoid obviously sensitive assets